In a nutshell

Access to social insurance has declined across the board in Egypt, even among regular wage workers, who are required to be covered by law.

The cost of contributions has been rising, mainly driven by a substantial increase in the minimum insurable wage since 2016, which has made the scheme much more expensive for regular wage workers, especially those in the lowest first and second wage quintiles.

Although the current design of social insurance seeks to include irregular workers, they are not obliged to participate; indeed, they are effectively excluded because of the cumbersome documentation that is required for them to enroll.

Can the design of social insurance schemes contribute to rising informality? There is a growing body of research evidence that institutional constraints and scheme design features (for example, the eligibility requirement for enrolment and the scheme’s affordability and benefit entitlements), can affect the behaviour of both employers and employees, eventually leading to gaps in social insurance coverage (Jiang et al, 2018; Lopez-Acevedo et al, 2023; Ringen and Ngok, 2017).

This column focuses on Egypt as a test case to explore how institutional constraints related to the design of its social insurance scheme can lead to the lack of social insurance. Recent work demonstrate that this decline in social insurance coverage was not driven by structural change or sectoral transformation in the economy (Assaad and Wahby, 2023). Therefore, a closer examination of the scheme’s design, by different employment status, is warranted.

We argue that the increase in cost for regular wage workers, and the legal informality of irregular wage workers are key to understanding the low and falling social insurance coverage in Egypt – see Selwaness and Barsoum (2023) for more details.

Costly formality for regular wage workers

Workers in regular jobs (those lasting at least six months) should be registered in the social insurance system through their employers. Their social insurance participation is obligatory: lack of coverage is illegal and reflects the discretion of their employers not to enrol them, whether based on mutual agreement or otherwise.

Indeed, employers are penalised for not conforming. Under the new law 148/2019, the penalty that employers must pay for not registering workers in social insurance increased to a minimum of 30,000 EGP and a maximum of 100,000 EGP – and it may potentially lead to jail (article 165). This is relative to a penalty of 1 EGP per worker with a maximum of 500 EGP in previous laws.

According to nationally representative microdata from the Labor Force Survey (LFS), the share of regular wage work in Egypt expanded from 24% in 2009 to 34% of total employment in 2021. Much of this 10 percentage point increase was in regular jobs with no coverage despite mandatory coverage. By 2021, only 35% of regular wage workers in the private sector were socially insured, down from 52% in 2009.

Our analysis shows that increases in the ‘minimum insurable wage’ made the scheme less affordable (to workers and their employers) over time. As with the previous social insurance laws, the new law continues to set a minimum and a maximum bound for the wage that is used to calculate contributions, known as the ‘insurable wage’.

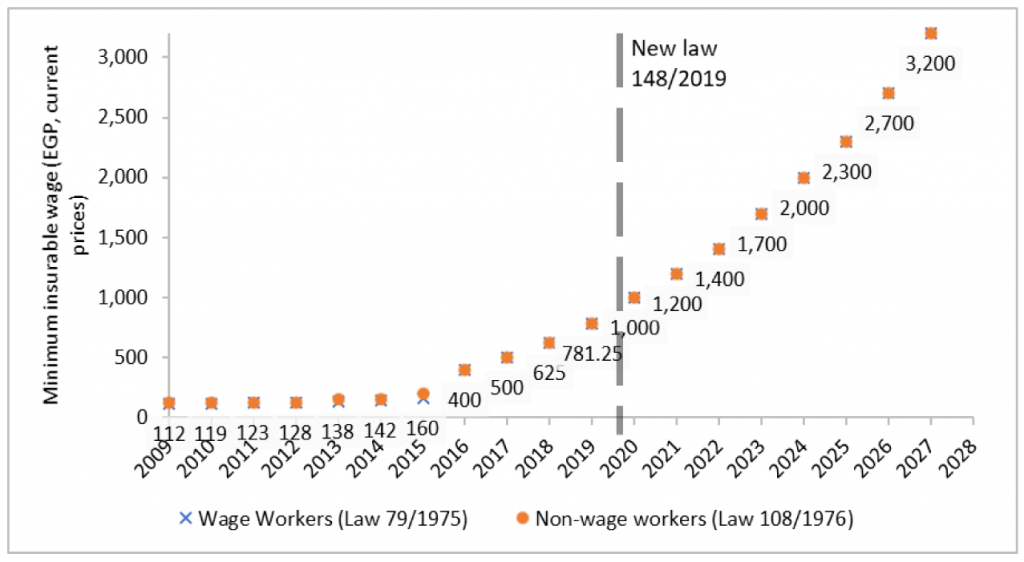

The minimum insurable wage increased substantially in 2016 to reach 400 EGP per month, up from 160 EGP per month (see Figure 1), followed by a 25% annual increase until 2020. Then, a new law 148/2019 came into effect in 2020, where the minimum insurable wage reached 1,000 EGP per month – see Barsoum and Selwaness (2022) for more details.

Figure 1: The evolution of the minimum insurable wage in current prices, 2009-28

Source: Ministry of Social Solidarity (Decisions No. 74 of 2013, No. 310 of 2017) and Prime Minister’s Decision No. 2437 of 2021.

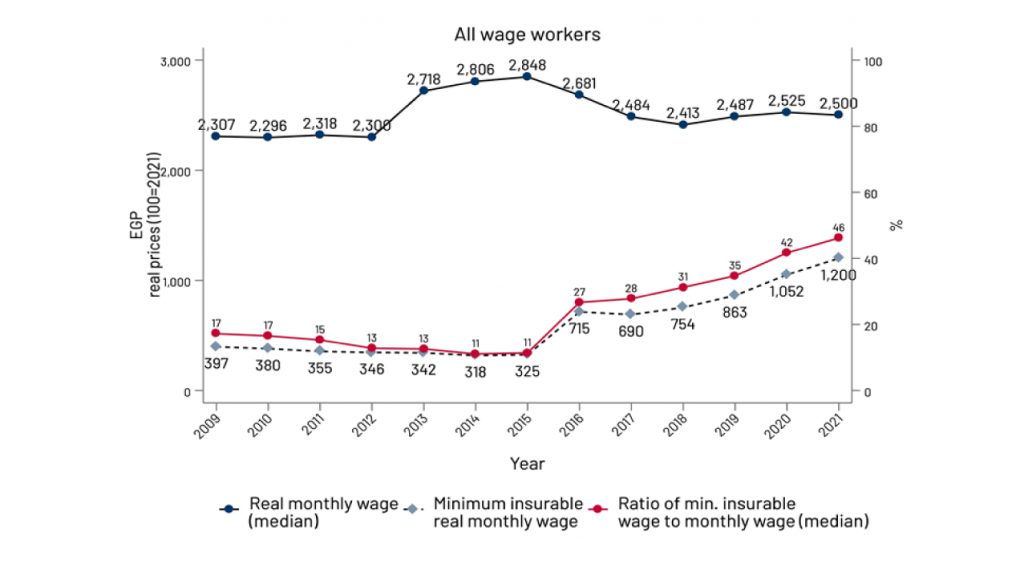

The series of increases in the minimum insurable wage has led to a serious implication: social insurance has become more costly since 2016, and it has happened in an unprecedented manner compared with the legacy of a nearly stagnant minimum insurable wage over previous years. The minimum bound rose faster than the monthly wage, and by 2021, the minimum insurable wage reached almost half of the median wage of regular wage workers, increasing up from 11%-17% of the median wage (see Figure 2).

The scheme has become especially expensive for low earners, as the insurable wage rose to reach double the median monthly wage of workers in the lowest wage quintile, and almost equal to that of workers in the second wage quintile.

Figure 2: The evolution of the minimum insurable wage, the median monthly wage and the ratio of insurable wage to median monthly wage

Source: LFS 2009-2021.

Despite the rising cost, not every insured wage worker can receive pensions. In the cases of reaching retirement age, suffering disability or survivorship, the worker is eligible for a retirement (or survivor) pension provided they have contributed for at least 10 years (120 months). Otherwise, there is no retirement pension, but rather an end-of-service compensation (calculated at 15% of annual income for each year of contributions).

Therefore, the system favours those who contribute at a young age and manage to accumulate as many years as possible, which is no longer adapted to the current realities of Egypt’s labour market. For example, women are one of the most penalised groups because they often drop out of the labour market at marriage (Assaad et al, 2022), and are likely not to meet the minimum period of contributions.

Legal informality for irregular wage workers

Irregular workers, which the new law 148/2019 (article 4) classified into specific categories (see Barsoum and Selwaness, 2022), have the choice of registering themselves in the social insurance scheme. But they are effectively excluded from the system because the required documentation to enrol is a serious hurdle. This documentation includes a national identity card showing that the worker’s occupation is one of those categories included in the law, which is hard to achieve for many irregular jobs.

Another required documentation is an employment history from the civil register, which is unlikely to be feasible given the nature of irregular jobs. Moreover, the law does not penalise the non-enrolment of irregular workers in the scheme. This means that their enrolment is practically on a voluntary basis, and hence their informality is legal.

Policy implications

Whereas the spirit of the new social insurance law shows a commitment to expanding coverage and including previously excluded workers, institutional constraints remain significant. Although the rising cost of the scheme, via the increase in the minimum insurable wage in 2016, is important for the financial viability of the system, it has led to a negative effect on coverage and an unintended loss of contributions from regular wage workers.

The inflation peak in Egypt in 2016 did not help, but it also accentuated the impact of the rising cost of the scheme. Furthermore, cumbersome and unattainable requirements for enrolment and eligibility for many of the previously excluded workers still represent a major obstacle.

Further information

Assaad, R, C Krafft and I Selwaness (2022) ‘The Impact of Marriage on Women’s Employment in the Middle East and North Africa’, Feminist Economics 28(2): 247-79.

Assaad, R, and S Wahby (2023) ‘Why is Social Insurance Coverage Declining in Egypt? A Decomposition Analysis’, ERF Working Paper No. 1658.

Barsoum, G, and I Selwaness (2022) ‘Egypt’s reformed social insurance system: How might design change incentivize enrolment?’, International Social Security Review 75(2): 47-74.

Jiang, J, J Qian and Z Wen (2018) ‘Social Protection for the Informal Sector in Urban China: Institutional Constraints and Self-selection Behaviour’, Journal of Social Policy 47(2): 335-57.

Lopez-Acevedo, G, M Ranzani, N Sinha and A Elsheikhi (2023) Informality and Inclusive Growth in the Middle East and North Africa (MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA DEVELOPMENT REPORT), World Bank.

Ringen, S, and K Ngok (2017) What kind of welfare state is emerging in China?, Springer.

Selwaness, I, and G Barsoum (2023) ‘When Formality Is Costly and Informality Is Legal: Social Insurance Design Woes at a Time of Economic Crises’, ERF Working Paper No. 1661.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a Ford Foundation grant to ERF for the project ‘Renewing the Social Contract: Working Toward a More Inclusive Social Insurance System in Egypt’. The authors appreciate the comments of Ragui Assaad and participants in the ‘Workshop on social insurance in Egypt’.