In a nutshell

Intimate partner violence in Egypt significantly undermines women’s labour supply, as well as their bargaining power within households; two critical factors are pivotal in influencing these dynamics: asset ownership and attitudes towards gender roles.

Women’s ownership of assets enhances their labour market participation and bargaining power, offering a degree of protection against the economic impacts of violence; conservative gender role attitudes are linked to a reduction in women’s bargaining power and increased susceptibility to violence.

Policy interventions should focus on promoting women’s education and asset ownership, reforming legal structures and shifting social norms to mitigate the effects of intimate partner violence, and to empower women economically and socially.

The pervasive and insidious nature of intimate partner violence (IPV), a predominant form of gender-based violence, poses a significant challenge to social stability and individual wellbeing globally. IPV is a universal issue that is firmly ingrained in social structures and gender dynamics, surpassing economic level, development stages and cultural origins.

In new research, we explore the complex relationship between IPV and women’s empowerment, highlighting the significant effects on labour market participation, social contribution and overall economic development. IPV mainly affects women and girls, resulting in varied immediate and lasting effects, such as physical, psychological, sexual and emotional harm.

The phenomenon causes immense damage to the victims and has far-reaching consequences for their families, communities and countries. It is associated with higher healthcare and legal costs, and reduced productivity; it also impedes overall socio-economic advancement.

Our study analyses the impact of IPV on labour supply and intra-household dynamics, focusing on the Egyptian context (Giovanis and Ozdamar, 2023). We contribute to existing evidence by exploring three forms of domestic violence – physical, psychological and sexual – and considering factors such as asset ownership and gender role attitudes. Using data from the Egypt Economic Cost of Gender-Based Violence Survey 2015, we seek to understand the dynamics of IPV within households and its broader socio-economic implications.

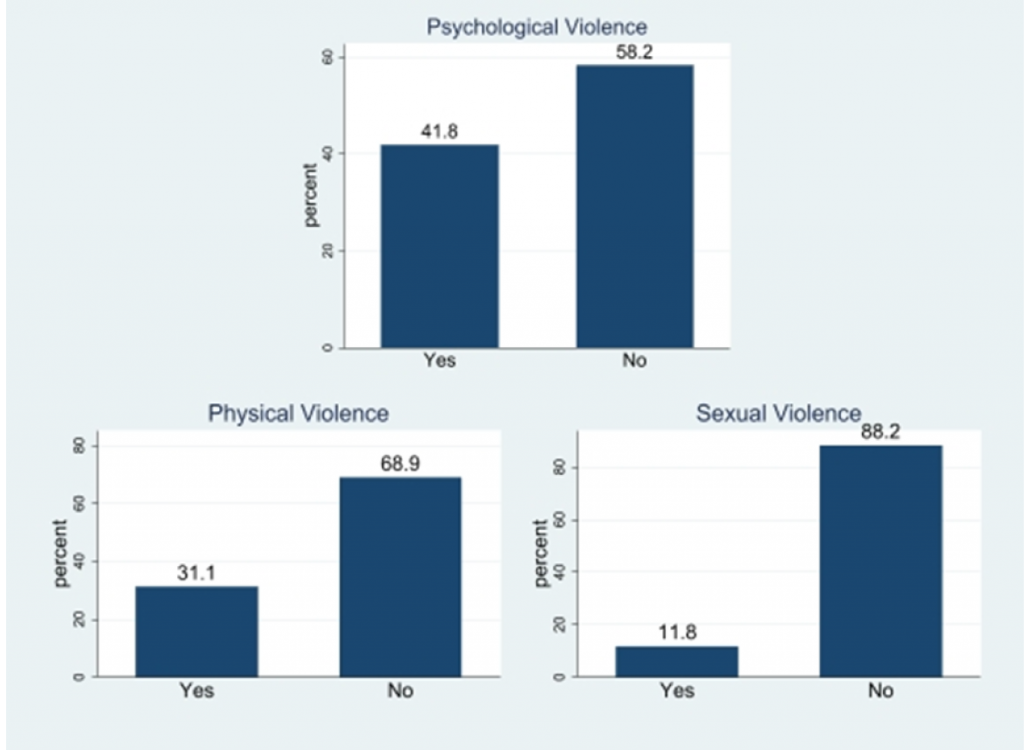

In Figure 1, we report the proportion of married women who have experienced domestic violence. A higher percentage has experienced psychological violence at 41.80%, followed by experience of physical violence at 31.13%, and experience of sexual violence at 11.76% of the sample.

Figure 1: Proportions of married women experiencing domestic violence

Understanding the far-reaching impact of IPV on women’s labour market outcomes is crucial for framing effective policies. IPV limits women’s ability to engage in paid work, earn income and exercise autonomy over family and personal decisions, thereby perpetuating cycles of poverty and inequality (Hidrobo et al, 2016; Bhalotra et al, 2021). Our study offers insights into the detrimental effects of IPV on women’s economic participation and empowerment, highlighting the need for policy interventions.

Key findings

Our findings highlight the impact of domestic violence on gender inequalities and the importance of women’s asset ownership in enhancing their bargaining power. The results show that for every 1 Egyptian pound increase in the wife’s wage, she transfers 0.28 to 0.34 pounds to her spouse. For the same increase, husbands transfer 0.15 to 0.19 pounds to their wives.

The annual wage reduction varies between 230 and 400 pounds, contingent on factors such as age disparities and attitudes towards gender roles. The reduction can reach 2,500 pounds per year if women have undergone any form of domestic violence from their partner, including physical, psychological or sexual abuse. More specifically, we find that:

Negative impact of IPV on women’s labour supply: IPV adversely affects women’s labour supply. Physical, psychological and sexual violence are all associated with a reduction in the number of working days for women, indicating a direct correlation between IPV and decreased participation of women in the workforce.

Influence of gender role attitudes and asset ownership: Conservative attitudes towards gender roles have a negative impact on women’s bargaining power and labour supply. Conversely, women’s ownership of assets increases their labour supply and bargaining power, suggesting that economic independence plays a crucial role in mitigating the effects of IPV.

Educational attainment and labour supply: Education is positively correlated with women’s labour supply but negatively correlated with men’s labour supply. This suggests that higher educational attainment among women can empower them and potentially reduce their vulnerability to IPV.

Sharing rules and bargaining power: Women tend to share a larger portion of any income increase with their partners than men do. This asymmetry indicates that women exhibit more altruistic behaviour within the household.

Costs of IPV: Women experiencing physical violence face the highest annual wage loss, followed by those subject to sexual and psychological violence.

Conclusion and policy implications

The impact of IPV on women’s labour supply and economic independence

Reduced labour participation: The direct correlation between IPV and a decrease in women’s labour supply underscores the pervasive impact of violence on women’s economic autonomy. This reduction in labour participation not only affects individual women’s economic and financial independence, but also has broader implications for social and economic development.

Bargaining power in households: IPV diminishes women’s bargaining power within households. This dynamic can perpetuate a cycle of dependency and violence, where women are unable to leave abusive relationships due to economic constraints.

The role of education and asset ownership

Empowering through education: Education emerges as a key factor in empowering women and reducing their vulnerability to IPV. Policies focused on increasing women’s educational attainment could be pivotal in breaking the cycle of violence and dependency.

Asset ownership as a buffer: Women’s asset ownership is positively correlated with increased labour supply and bargaining power. This suggests that economic policies aimed at promoting women’s property and asset ownership could be effective in mitigating the impact of IPV.

Policy implications

Economic interventions: The findings highlight the need for economic interventions, such as promoting women’s entrepreneurship and asset ownership, to empower women financially and reduce their vulnerability to IPV.

Legal and social reforms: Strengthening legal frameworks to protect women from IPV and changing social attitudes towards gender roles are critical. Public awareness campaigns and education programmes can play a significant role in shifting social norms and reducing IPV.

Health and social services: Providing accessible health and social services for IPV survivors is crucial. These services not only aid in immediate recovery but also support women in regaining their economic footing.

The empirical findings of this study contribute to the understanding of IPV’s impact on labour supply and intra-household dynamics in Egypt. They highlight the need for multifaceted policy interventions focusing on education, economic independence and legal frameworks to address IPV effectively.

By understanding the multifaceted impact of IPV on women’s economic participation and empowerment, policy-makers and stakeholders can develop more effective strategies to combat this pervasive issue.

Ultimately, addressing IPV is not just a matter of justice for individual women but also a crucial step towards achieving broader goals for social and economic development. This study paves the way for further research and policy development aimed at empowering women and mitigating the detrimental effects of IPV.

Further reading

Bhalotra, S, U Kambhampati, S Rawlings and Z Siddique (2021) ‘Intimate partner violence: The influence of job opportunities for men and women’, World Bank Economic Review 35(2): 461-79.

Hidrobo, M, A Peterman and L Heise (2016) ‘The effect of cash, vouchers, and food transfers on intimate partner violence: Evidence from a randomized experiment in Northern Ecuador’, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 8(3): 284-303.

Giovanis, E, and O Ozdamar (2023) ‘Intra-Household Bargaining, Resource Allocation and Cost of Gender-Based Violence in Egypt: The Role of Asset Ownership and Gender Role Attitudes’, ERF Working Paper No. 1670.