In a nutshell

There is a positive labour productivity premium for exporting and importing firms in Egypt; this is due to learning-by-exporting effects and access to foreign inputs from the forefront of knowledge and technology, which are increasingly beneficial for firms in technology-intensive sectors.

Economies of scale and higher productivity channels – rather than the skill characteristics of workers or the composition of the labour force – explain the positive wage premia of trading firms.

Firms’ participation in trade enhances labour market outcomes for women: it reduces the gender wage gap; and it leads to a higher share of women workers employed, especially in low-technology export sectors.

While there are numerous empirical studies documenting the link between trade activity and labour market outcomes, such evidence for Egypt’s economy has been weak to date. The country has signed several trade agreements, which has led to a surge in its exports. But this has not been translated into favourable outcomes in the form of rising wages nor increased labour market participation of women.

Data from Egypt’s labour force surveys indicate that average wages steadily increased from 2009, but then decreased in 2017. There has also been a persistent wage gap between men and women workers of about 8% after controlling for educational attainment, hours worked and the industry of employment (Robertson et al, 2021). According to estimates from the International Labour Organization (ILO), women’s labour market participation in Egypt has been low, and it decreased further from 23% in 2009 to 15% in 2021.

A firm-level study of trade and labour outcomes in Egypt

A recent study of Egypt (Kamal, 2024) examines the impacts of a manufacturing firm’s trading status (exporting/importing of intermediate inputs) on its labour productivity, average real wages and share of women workers. The research differentiates between sectors according to the intensity of their use of technology.

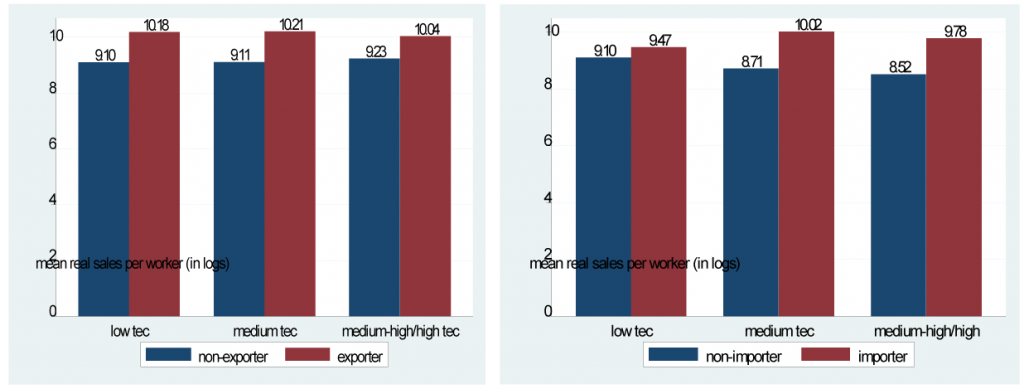

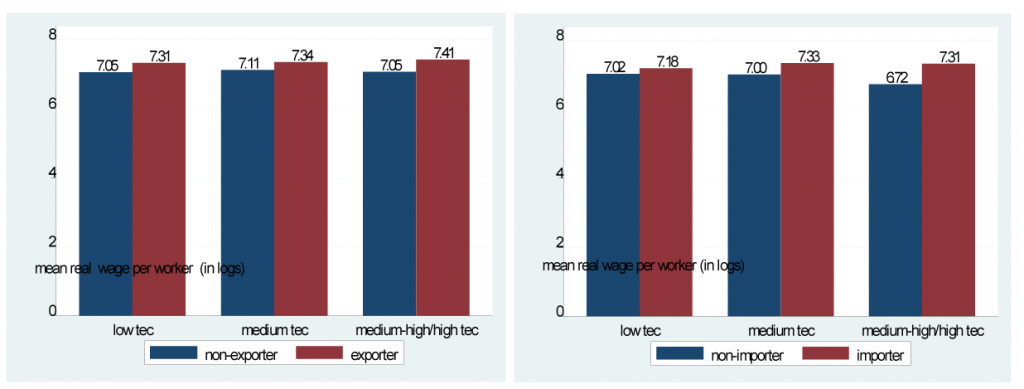

According to the World Bank’s Enterprise Survey data for Egypt in 2020, exporters are more productive than non-exporters in all sectors. What’s more, productivity is higher for firms that import their inputs compared with non-importers, especially those operating in medium, medium-high and high-technology sectors (see Figure 1). In addition, there is a higher wage premium for trading firms in all sectors and it is more pronounced for importers (see Figure 2).

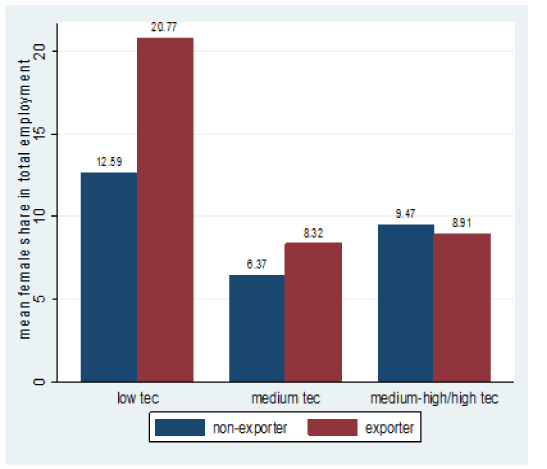

Moreover, being an exporter – rather than an importer – is the factor that matters for increasing the share of women workers in a firm’s total employment. But there are differences across sectors: the women’s labour share premium in exporters compared with non-exporters is highest in low-technology sectors, while this effect is reversed in medium-high and high-technology sectors (see Figure 3).

Figure 1: Average labour productivity (in logs) by trading status and sector technological intensity

Source: constructed by the author using manufacturing firm-level data of the World Bank Enterprise Survey, Egypt 2020

Figure 2: Average wage per worker (in logs) by trading status and sector technological intensity

Source: constructed by the author using manufacturing firm-level data of the World Bank Enterprise Survey, Egypt 2020

Figure 3: Average women’s employment share (%) by trading status and sector technological intensity

Source: constructed by the author using manufacturing firm-level data of the World Bank Enterprise Survey, Egypt 2020

Quantified effects

The research has several empirical results.

Productivity

Exporters are on average 61% more productive than non-exporters; while importers are 36% more productive than non-importers.

The exporter productivity premium is highest for small firms, reflecting their higher benefits from ‘learning-by-exporting’. The importer productivity premium gets larger as the sector becomes more technologically intensive.

Wages

Exporters pay significantly higher average wages than non-exporters with a premium of 16%, while importers have a wage premium of 21%. Economies of scale and productivity channels – rather than the skill characteristics of workers or the labour force composition – explain the wage premia for trading firms.

In addition, the gender wage gap is reduced in exporting and importing firms, although it does not disappear completely.

Women’s employment share

The share of women workers in total employment is 2.4% higher in exporting firms than in non-exporting firms. Conversely, there is no significant effect of firm importing on women’s employment share.

Exporters have the highest women’s employment share premium in low-technology sectors (4.84%), followed by medium-technology sectors (2.76%), while exporters hire a lower share of women workers in medium-high and high-technology sectors (-1.83%) than non-exporters. These results are primarily driven by the share of women ‘production’ workers.

Conclusion

Favourable micro-level labour impacts of trade are evident from this research. These effects mainly stem from the productivity and profitability superiority of exporting and importing firms, which pay their workers higher average wages in a rent-sharing setting and are less likely to practice inefficient gender discriminatory practices.

In addition, women can achieve the largest employment gains as production workers in low skill-intensive export sectors such as food and textiles.

For these impacts to achieve wide-ranging improvements in growth rates, poverty reduction and gender equality, more efforts should be made to reform the business environment to enable greater private sector participation in the Egyptian economy.

It is also vital to have more entry of small and medium-sized firms into export markets as export activity is dominated by few large firms known as ‘export superstars’ (Freund and Pierola, 2015). There should also be an easier access for firms to essential imported inputs, especially those operating in technologically advanced sectors.

Further reading

Freund, C, and M Pierola (2015) ‘Export Superstars’, Review of Economics and Statistics 97(5): 1023-32.

Kamal, Y (2024) ‘The Effects of Trade Participation on Labor Productivity, Wages and Female Employment: Evidence from Egyptian Manufacturing Firms’, Journal of Economic Integration (forthcoming).

Robertson, R, M Bahena, D Kokas and G Lopez-Acevedo (2021) International Trade and Labor Markets: Evidence from the Arab Republic of Egypt, World Bank.