In a nutshell

Sudan experienced negative growth even prior to the pandemic; Covid-19 compounded pre-existing political, economic and labour market challenges.

The majority of Sudanese workers are under-employed, working relatively few hours, which is symptomatic of the country’s under-utilisation of its labour force; most workers are self-employed, primarily in agriculture and retail trade.

Sudan has limited data available to understand the labour market or to inform policy; collecting and making publicly available nationally representative labour and poverty data is essential for undertaking effective policy responses to Sudan’s challenges.

When the pandemic began, initial government actions in Sudan included closures, restrictions on internal movement and gathering, and some lockdown measures (Central Bureau of Statistics and World Bank, 2020; Hale et al, 2021). Closures helped to protect public health, but presented a substantial challenge to livelihoods and household welfare (Central Bureau of Statistics and World Bank, 2020).

The Sudanese government also undertook a number of actions to support the economy, firms and workers. Initial measures in response to the pandemic included increasing salaries for public sector employees and wage subsidies to small firms affected by the pandemic, measures to provide unemployment benefits to laid-off workers and measures to protect loans and banking (UNECA, 2020).

Cash assistance, along with food and hygiene assistance, were provided to families during the initial lockdown period (UNICEF, 2020). In 2021, Sudan began rolling out the Sudan Family Support Programme (SFSP or ‘Thamarat’) nationally, aiming to provide cash transfers to up to 80% of Sudanese families (Sudan Family Support Programme, 2021).

But domestic currency depreciation and high levels of debt and inflation constrained Sudan’s ability to provide social protection and an effective Covid-19 response (UN-ESCWA, 2021). The pandemic also overlapped with a period of political instability and uncertainty.

The transitional government in Sudan was installed and internationally recognised in 2019. Floods, inflation and the risk of renewed protests, on top of the pandemic, contributed to the declaration of an economic emergency in 2020 (UN-ESCWA, 2021).

On 25 October 2021, the military detained civilian members of the transitional government. But after counter-protests, attempts were made to reinstate civilian leaders. The prime minister resigned after he was unable to form a government in the face of ongoing anti-military protests.

These political difficulties continue to limit Sudan’s economy and response to continuing health and economic challenges. Due to political, economic and pandemic challenges, Sudan’s real annual GDP growth rate shows the economy contracted throughout the period 2018-20. Although growth was 0.7% in 2017 (World Bank, 2022) it fell to -2.7% in 2018, -2.2% in 2019 and -3.6% in 2020. These growth challenges have contributed to challenges in the labour market as well.

To assess the labour market in Sudan, this column uses data from two waves of the ERF COVID-19 MENA Monitor Household Surveys (in April 2021 and August 2021 (OAMDI, 2021)). It is important to note that this is a mobile phone survey with a sample of around 2,000 individuals aged 18 to 64, and is thus a selected segment of Sudan’s labour market: working-aged adults owning mobile phones.

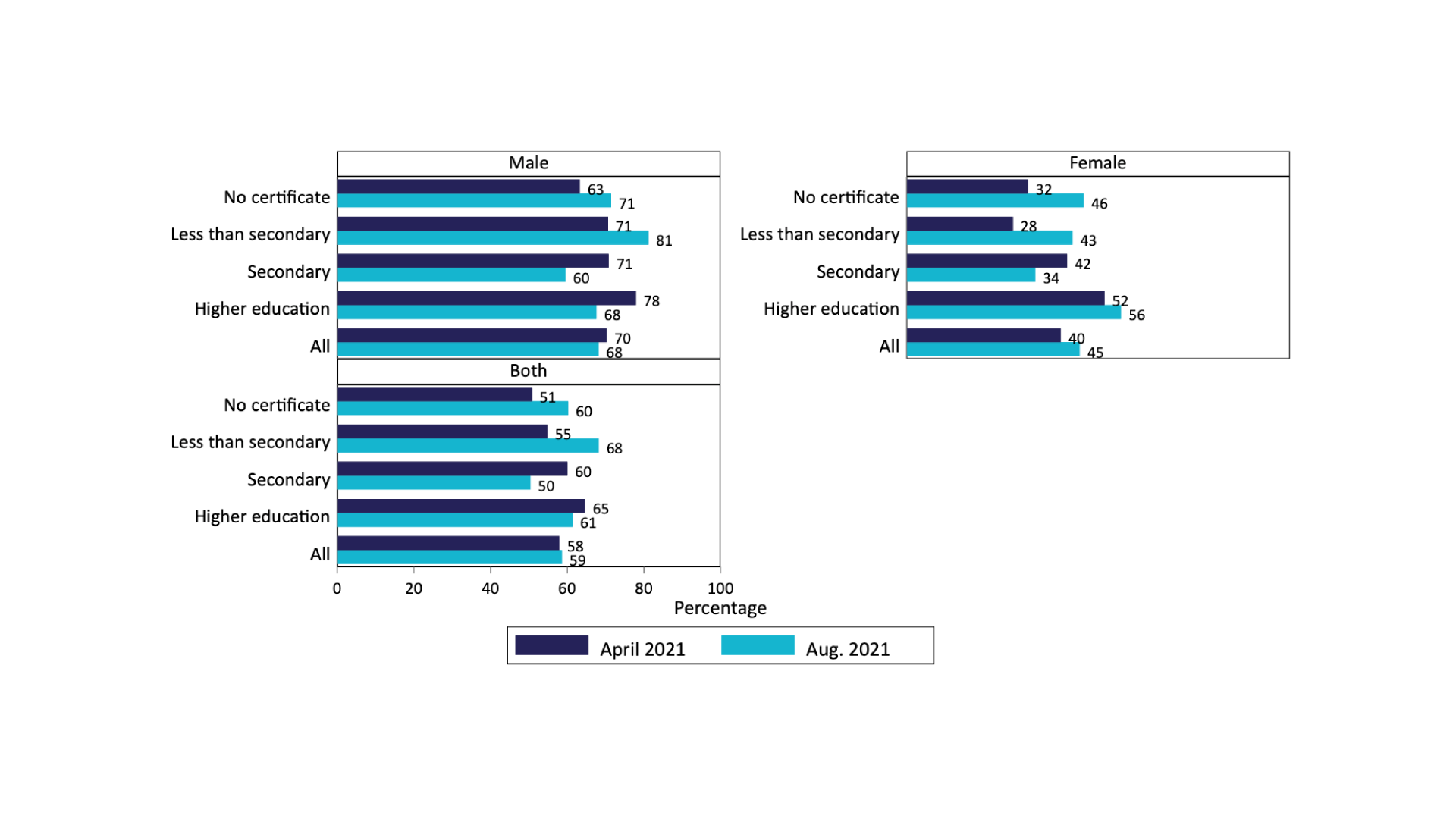

Overall, as Figure 1 shows, there is a gender gap in labour force participation, as the rate for men (68% in August 2021) is higher than for women (45%; 59% rate overall). But from April to August 2021, the labour force participation rate decreased slightly (from 70% to 68%) for men and increased (from 40% to 45%) for women. There are no large differences in labour force participation by education, which is consistent with past research showing relative convergence by education (Ebaidalla and Nour, 2021).

Figure 1: Labour force participation rate (percentage of population aged 18-64), by wave, educational attainment and sex

Source: Authors’ calculations, based on COVID-19 MENA Monitor.

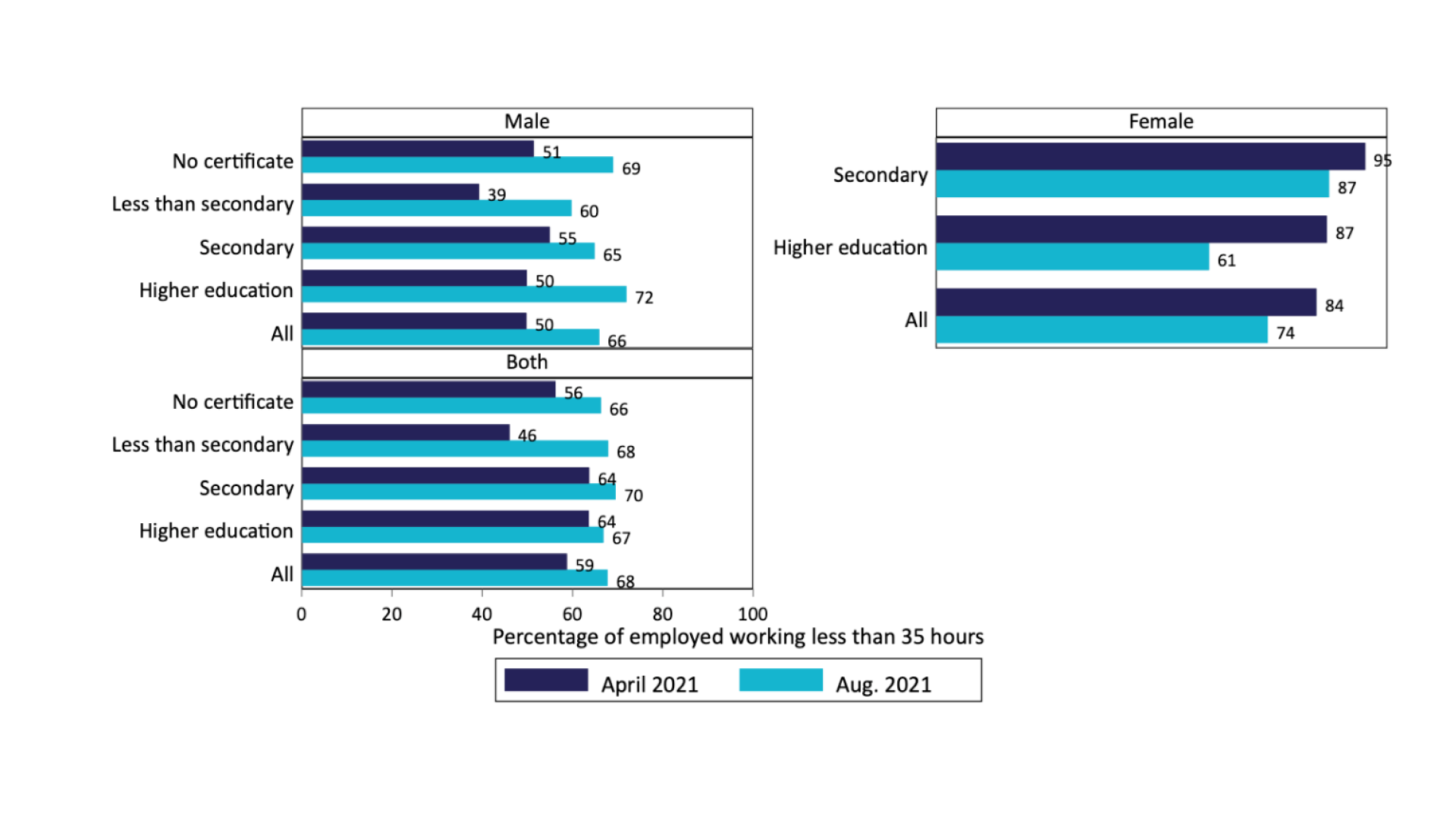

The time-related under-employment rate is the share of individuals in employment working fewer than 35 hours per week. This metric tends to be a better measure of labour market vulnerability than open unemployment (Assaad, 2019).

Overall, time-related under-employment is high in Sudan, with 59% of workers under-employed in April 2021 and 68% in August 2021 (Figure 2). While the employment-to-population ratio increased in this period, hours of work show more under-employment, which may be related to additional employment in agriculture, but for shorter hours.

While under-utilisation of labour is common in developing countries, Sudan’s under-employment has reached an alarming level, which may be in part related to the pandemic and lockdowns.

Figure 2: Time-related under-employment rate (percentage of the employed aged 18-64), by wave, educational attainment and sex

Source: Authors’ calculations, based on COVID-19 MENA Monitor.

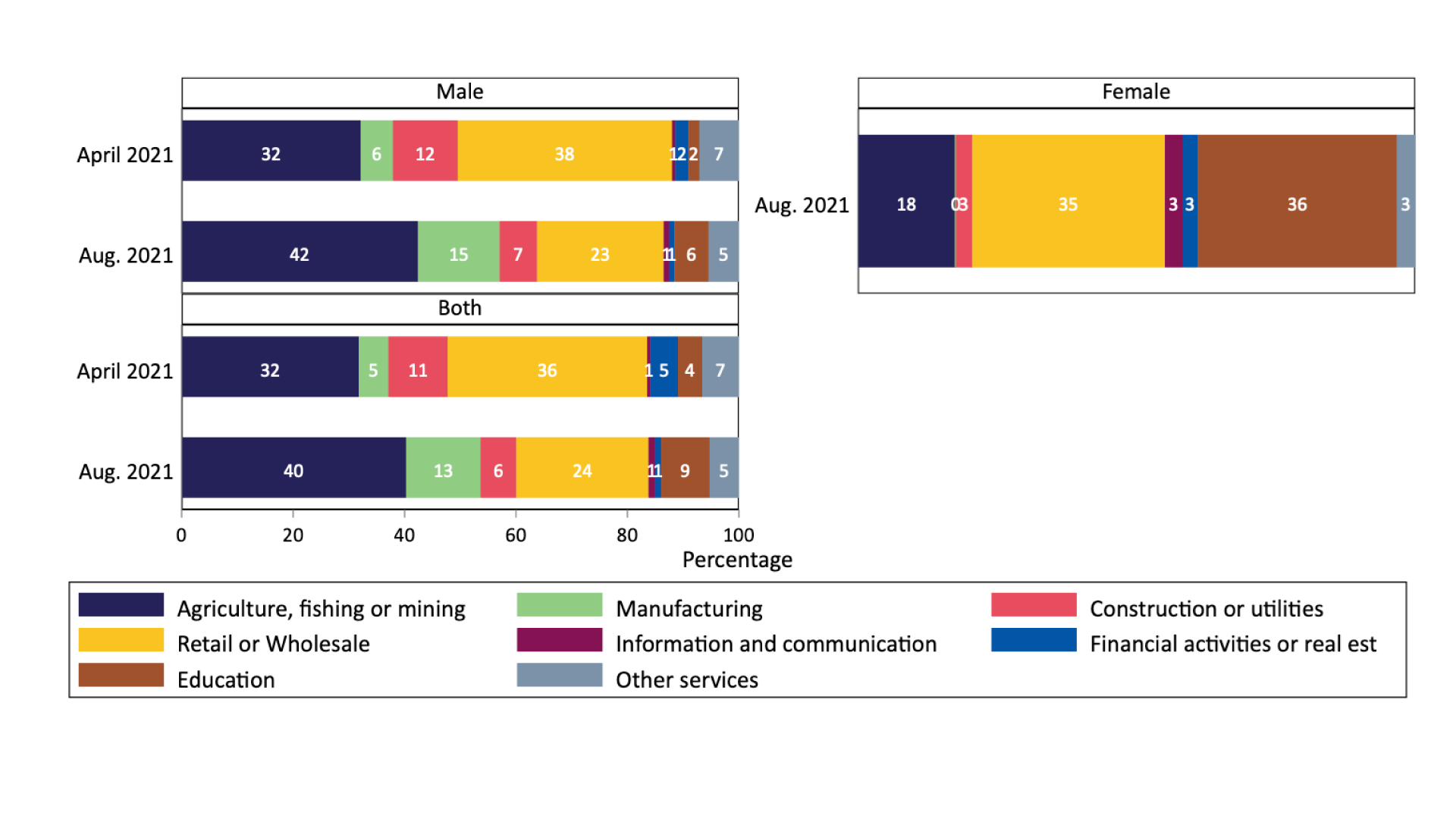

A key feature of employment in Sudan is that it is primarily self-employment. In August 2021, 74% of the employed were self-employed. Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of employment (percentage of the employed aged 18–64) by economic activity and sex.

The two largest activities in Sudan are agriculture (40% of employment in August 2021) and retail or wholesale (24% of employment in August 2021). From April to August 2021, employment increased substantially in the agriculture sector (from 32% to 40%). Employed women were particularly likely to be in the education sector (36% in August 2021), retail or wholesale (35%) or agriculture (18%).

Figure 3: Distribution of employment (percentage of the employed aged 18-64), by wave, economic activity and sex

Source: Authors’ calculations, based on COVID-19 MENA Monitor.

Sudan has faced a number of growth and labour market challenges since 2018. As highlighted in other research (Ebaidalla and Nour, 2021; Krafft et al, 2022; Nour, 2022a, 2022b, 2022c), a number of long-standing economic challenges as well as recent economic and political developments have contributed to Sudan’s difficulties.

For example, political instability led to a pause in donor support for the Sudan Family Support Programme (World Bank, 2022b). Restoring political stability is an essential precursor to addressing Sudan’s jobs and growth challenges.

Sudan is also a data-scarce environment. The last official labour force survey was in 2011 and the last nationally representative household budget survey was in 2014/15. The COVID-19 MENA Monitor provides important data, but for a selected, mobile phone-owning segment of the population and a finite set of variables (limited by the length of phone surveys).

Collecting and making publicly available nationally representative labour and poverty data is essential for undertaking effective policy responses to Sudan’s challenges.

References

Assaad, R (2019) ‘Moving beyond the Unemployment Rate: Alternative Measures of Labor Market Outcomes to Advance the Decent Work Agenda in North Africa’, Approach Paper: Expert Group Meeting, December 2019.

Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) and World Bank (2020) ‘Socioeconomic Impact of COVID-19 on Sudanese Households’.

Ebaidalla, EM, and SSOM Nour (2021) ‘Economic Growth and Labour Market Outcomes in an Agrarian Economy: The Case of Sudan’, in Regional Report on Jobs and Growth in North Africa 2020 (pp 152-82). International Labour Organization (ILO) and ERF.

Hale, T, N Angrist, R Goldszmidt, B Kira, A Petherickm T Phillips, S Webster, E Cameron-Blake, L Hallas, S Majumdar and H Tatlow (2021) ‘A Global Panel Database of Pandemic Policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker)’, Nature Human Behaviour 5: 529-38.

Krafft, C, SSOM Nour and EM Ebaidalla (2022) ‘Jobs and Growth in North Africa in the COVID-19 Era The Case of Sudan (2018-21)’, in Second Regional Report on Jobs and Growth in North Africa (2018-21): Developments through the COVID-19 Era, ERF and ILO.

Nour, SSOMS (2022a) ‘The Impact of Covid-19 on the MENA Labor Market: The Case of Sudan’, ERF Policy Brief No. 87.

Nour, SSOMS (2022b) ‘The Impact of COVID-19 on Households and Firms in the MENA Region: The Case of Sudan’, AFD Research Papers No. 250.

Nour, SSOM (2022c) ‘The Impact of Covid-19 on the Labour Market in Sudan’, The Forum: ERF Policy Portal.

OAMDI (2021) COVID-19 MENA Monitor Household Survey (CCMMHH). Version 5.0 of the Licensed Data Files; CCMMHH_Nov-2020-Aug-2021.

Sudan Family Support Programme (2021) Thamarat: Supporting Sudanese Families.

UN-ESCWA (2021) Arab LDCs: Development Challenges and Opportunities.

UNICEF (2020) UNICEF Sudan – COVID-19 Response 2020.

UNECA, United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (2020) COVID-19 Crisis in North Africa: The Impact and Mitigation Responses. COVID-19 Response.

World Bank (2022a) ‘World Development Indicators’, World Bank Databank.

World Bank (2022b) ‘Frequently Asked Questions on the Recently Approved Emergency Safety Nets Project in Sudan‘.