In a nutshell

As individuals feel more autonomous and capable of shaping their lives, they lean slightly more towards the independence and potential for control offered by self-employment; this feeling is weaker among religious individuals.

Individuals who place high importance on God in their lives might have a value system that influences their perception of risk, success and the nature of work: they might prefer employment, which is seen as more secure and stable than the uncertainties of self-employment.

Among less religious individuals, a higher locus of control discourages self-employment; among more religious individuals, a higher locus of control encourages self-employment – this suggests that faith in divine guidance does not negate personal agency but rather enhances it.

Self-employment in Middle East and North African (MENA) countries is often considered a pathway to economic independence and a response to the lack of formal employment (Angel-Urdinola and Tanabe, 2012). It is influenced by a number of factors, including demographic and socio-economic conditions, individual personality traits, cultural norms and values, and personal beliefs (Aydoğan and Sevencan, 2018). The latter two factors are shaped by religiosity, which typically has profound effects on daily life, governance, legal frameworks and business practices.

Research indicates that internal locus of control – the belief that the outcomes of people’s actions are the result of their own behaviour – encourages individuals to take risks by instilling a belief in their ability to shape their future. But religiosity’s impact on risk varies: it can either promote risk-taking behaviour or encourage stability (Audretsch et al, 2013).

Religiosity may encourage collectivism and communitarianism, while internal locus of control may be indicative of individualism. Individuals with a strong internal locus of control prefer autonomy, aligning with the entrepreneurial desire for personal achievement. Religiosity can guide people towards stability or autonomy, influenced by the intersection of religious values with personal and professional goals (Kumar et al, 2021).

In addition, religiosity shapes networking by influencing values in business relationships, potentially providing access to community-based networks and facilitating trust within religious communities, thus supporting entrepreneurial ventures (Giacomin et al, 2023).

In a recent study (Bassil et al, 2024), we examine the determinants of the likelihood of self-employment in 12 MENA countries: Algeria, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Palestine, Qatar, Tunisia and Yemen. We use two metrics for religiosity that reflect its multidimensional nature: self-identification as religious (‘subjective religiosity’); and religious intensity, measured by the importance of God in an individual’s life (‘religious salience’).

In addition, we explore how religiosity interacts with internal locus of control either to encourage or to discourage individuals from pursuing self-employment.

Key results

The data we analyse are extracted from waves 6 and 7 of the World Values Survey. The dependent variable, self-employment, equals 1 if the person answers ‘self-employed’ to the question ‘are you employed now?’ and 0 otherwise. Subjective religiosity equals 1 if respondents describe themselves as ‘a religious person’ when asked ‘independently of whether you attend religious services or not, would you say you are …?’. Religious salience takes discrete values between 1 and 10, where 10 means that God is very important in the respondent’s life.

Our correlation analysis shows that internal locus of control is positively correlated with self-employment, while the two measures of religiosity are negatively correlated with self-employment. Moreover, we find a positive correlation between religiosity and internal locus of control. This last result suggests that religiosity fosters internal locus of control, where individuals believe that their efforts can directly influence their outcomes.

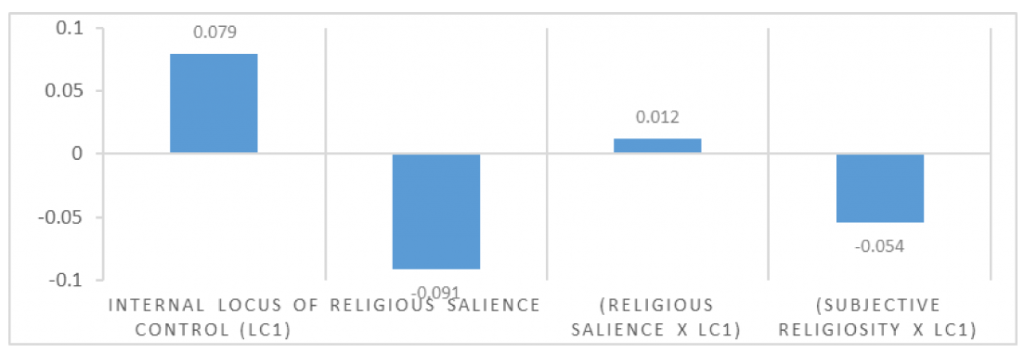

Figure 1 shows what the analysis reveals about the impacts of internal locus of control and religiosity on the likelihood of self-employment.

Figure 1: The impact on self-employment

The results indicate that internal locus of control promotes self-employment (0.079). But this effect is less pronounced among individuals who self-identify as religious, it is equal to 0.029 (0.079-0.054).

We also find that religious intensity has a negative effect on the likelihood of self-employment (-0.091). This suggests a trend where individuals with higher religious salience are less likely to choose self-employment. The effect of internal locus of control on self-employment depends on the intensity of religiosity. It is significantly higher for individuals that consider God to be of high importance in their lives (0.012).

Key insights

Individuals with a high internal locus of control are more inclined to embrace the responsibilities and risks of self-employment. This trend may be due to the entrepreneurial belief that one’s actions significantly affect outcomes. These individuals are proactive, seeking to shape their careers based on personal preferences and goals. Self-employment provides an opportunity for them to make decisions, and directly experience the outcomes of their actions, aligning with their desire for self-determination and personal agency.

In addition, perceived control over one’s life influences risk assessment and tolerance. Those who feel in control are more likely to view self-employment’s uncertainties as manageable challenges or opportunities for growth, making them more inclined to pursue this path.

Religious salience reflects the importance of God in an individual’s life, influencing their value system and worldview, including perceptions of risk, success and the nature of work. Individuals valuing high religious salience may prefer more stable and secure employment, aligning less with the uncertainties of self-employment.

This preference can also stem from cultural norms within religious communities, which might place more priority on community-oriented employment over entrepreneurial ventures. In addition, for religious individuals, community networks may offer support and opportunities in traditional employment sectors.

The effect of internal locus of control on self-employment varies with religiosity levels. It increases among highly religious individuals, indicating that religiosity can play a buffer role in reducing the risks and uncertainties that come with self-employment. Hence, religiosity does not negate personal agency but rather enhances it.

A call to action for MENA policy-makers

First, nurturing a sense of autonomy – where individuals feel in control of their economic destinies and are motivated to innovate – is key. This can be achieved through policies that bolster personal empowerment.

Second, since religiosity plays a pivotal role in shaping individuals’ career decisions, often tilting them away from self-employment due to their quest for stability and a balanced lifestyle, understanding these nuances is essential for crafting a broad-based economic strategy.

To this end, policy-makers should:

- Ensure that entrepreneurial initiatives resonate with religious beliefs and ethical standards by endorsing business practices that are both ethical and socially beneficial.

- Enhance support mechanisms in line with religious doctrines, such as financial options that adhere to religious teachings – for example, to Islamic banking principles.

- Develop educational/training programmes and adopt policies that promote higher levels of internal locus of control, self-esteem and self-efficacy.

These strategies not only shed light on labour market trends, but also pave the way for stimulating business activities and economic growth in the MENA region, making it a fertile ground for inclusive economic progress.

Further reading

Angel-Urdinola, D, and K Tanabe (2012) ‘Micro-determinants of informal employment in the Middle East and North Africa region’.

Audretsch, DB, W Bönte and JP Tamvada (2013). ‘Religion, social class, and entrepreneurial choice’, Journal of Business Venturing 28(6): 74-789.

Aydoğan, ET, and A Sevencan (2018) ‘The effect of entrepreneurship on economic growth: a panel approach in MENA countries’, in Entrepreneurship Ecosystem in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), Springer.

Bassil, C, MM Parast and A Safari (2024) ‘Faith and Entrepreneurship: Navigating the Impact of Religiosity on Self-Employment in the MENA Region’.

Giacomin, O, F Janssen, RS Shinnar, K Gundolf and N Shiri (2023) ‘Individual religious affiliation, religiosity and entrepreneurial intentions among students in four countries’, International Small Business Journal 41(3): 318-46.

Kumar, S, S Sahoo, WM Lim and L-P Dana (2022) ‘Religion as a social shaping force in entrepreneurship and business: Insights from a technology-empowered systematic literature review’, Technological Forecasting and Social Change 175(5-6).

This project was made possible through the support of a grant from Templeton World Charity Foundation, Inc (funder DOI 501100011730) through grant [grant DOI https://doi.org/10.54224/30453]. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Templeton World Charity Foundation, Inc.’