In a nutshell

Working illegally and informally (lacking a contract or social insurance) remains common among Syrian refugees in Jordan, despite the work permit programme.

Refugees may choose not to obtain work permits due to a perceived higher risk of exploitation, fear of losing other aid or costs such as social security.

One possible way to increase the proportion of refugees in the labour force and with legal protections would be to change the annual renewal of the work permit to a more substantial increment of time.

The conflict in Syria has created millions of refugees, including almost 1.3 million Syrians living in Jordan. Opportunities to work and earn an income can be important strategies for such refugees to meet their needs (Krafft et al, 2018).

Jordan does allow refugees to work legally. In 2016, the Jordanian government and the European Union created the ‘Jordan Compact’, which features provisions to support Syrian refugees in Jordan, including a work permit programme. Work permits are mandatory in Jordan for refugees to be legally employed.

The Jordan Compact includes a limit on the number of permits that can be issued to refugees as well as conditions to try to generate jobs for Jordanians, in case allowing Syrians to work displaces Jordanians from jobs. The work permits cover only certain sectors of work (mainly agriculture, construction and manufacturing) and they must be renewed annually.

Although in theory the basic work permit has a fee, it has repeatedly been waived (Kelberer, 2017). If a refugee is caught working without a permit, it could result in being sent to a camp or even deported back to Syria.

Few Syrians are in Jordan’s labour force

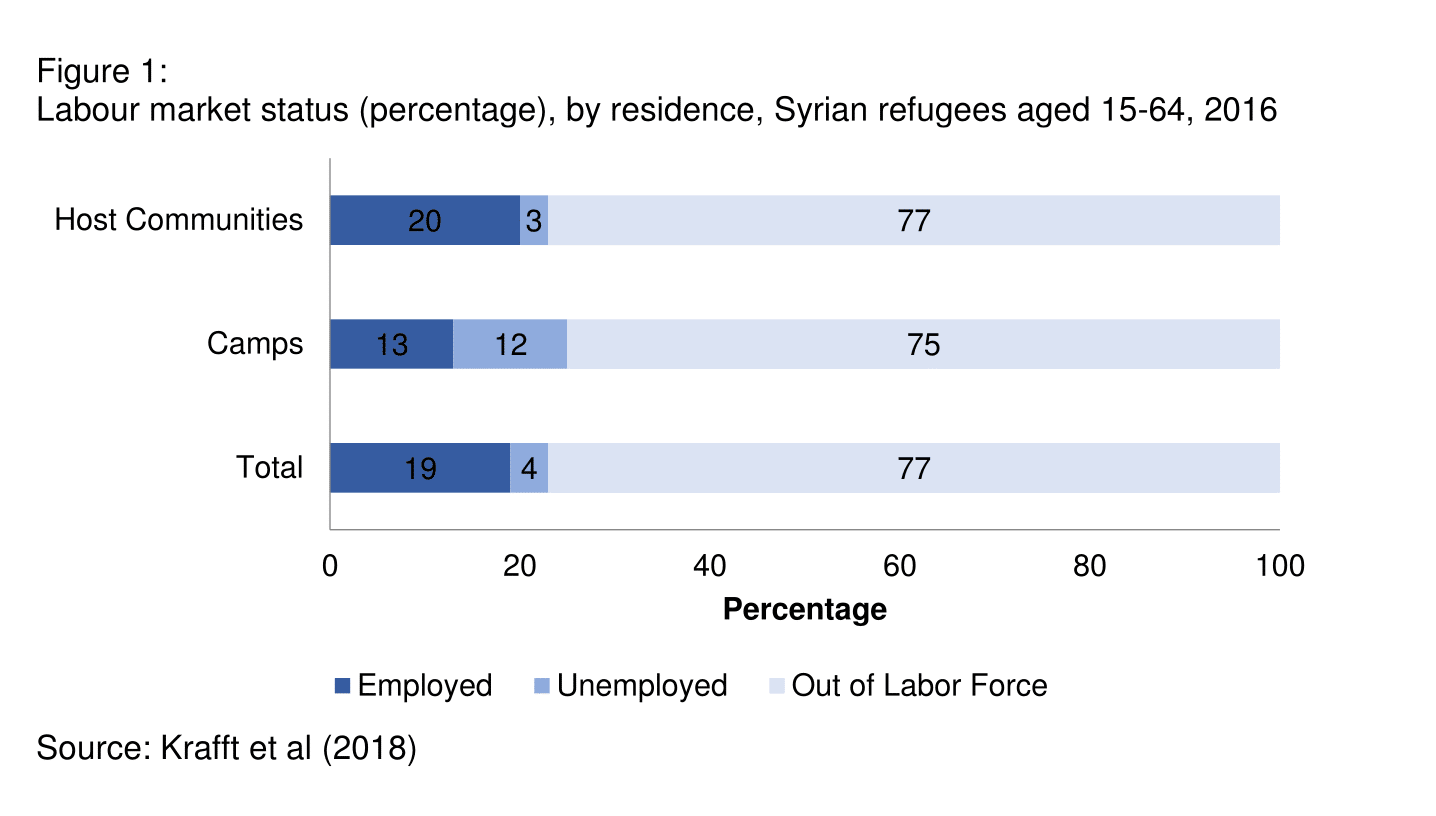

Despite the introduction of the work permit programme, the labour force participation of Syrian refugees in Jordan is very low. Based on results from the new Jordan Labor Market Panel Survey 2016, the majority (77%) of Syrian refugees are out of the labour force (Krafft et al, 2018). Labour force participation varies slightly for recent refugees between refugee camps and host communities.

Figure 1 shows the labour market status of Syrian refugees aged 15-64 by their area of residence. They can either be in the labour force (employed or unemployed) or out of the labour force. Labour force participation is slightly higher in camps (25%) than in host communities (23%). However, employment is much higher in host communities (20%) than camps (13%). Almost half of those participating in the labour market in camps are unemployed.

Working Syrians are primarily informally employed and lack permits

Working illegally and informally remains common among refugees, despite the work permit programme. Only 46,717 permits were issued to Syrian refugees in 2017, fewer than capacity (Ministry of Labour Syrian Refugee Unit, 2018).

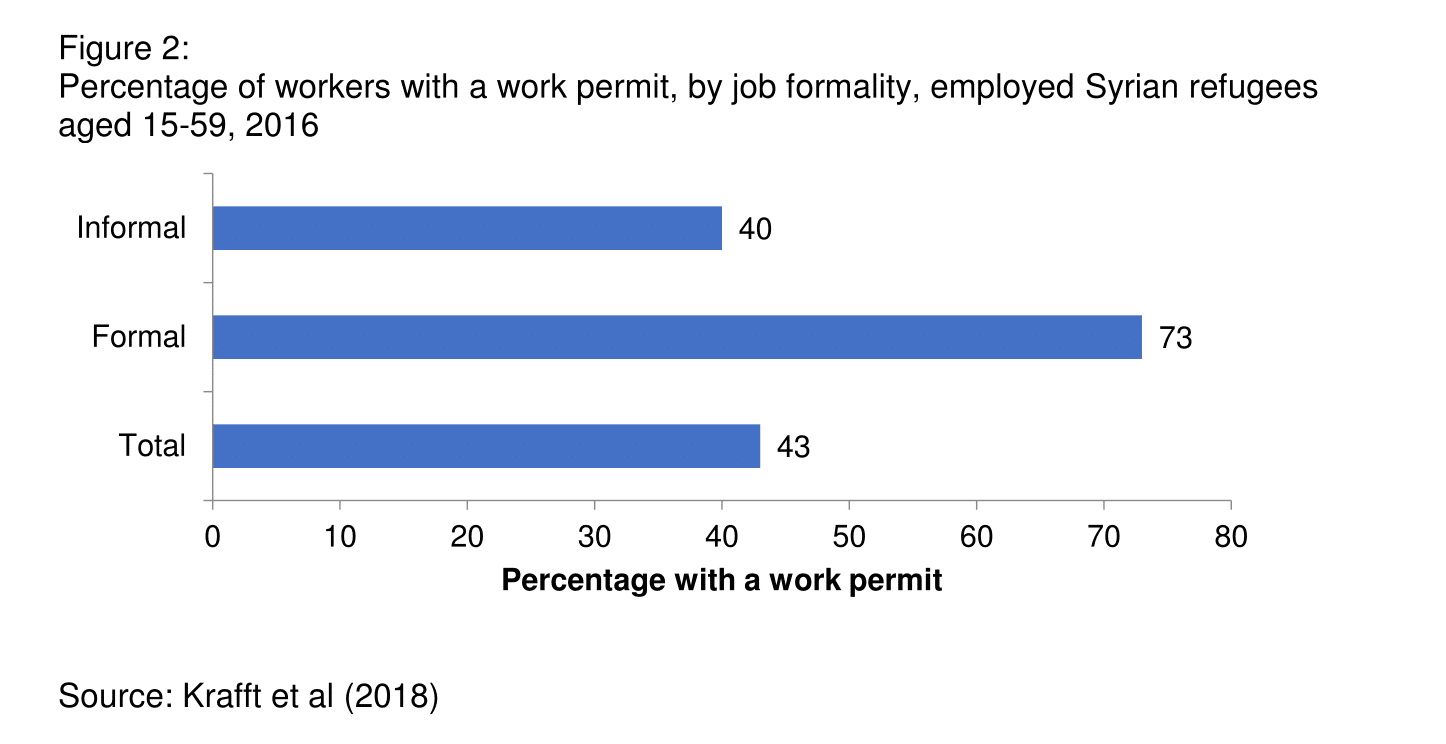

Although the low number is partly due to relatively few Syrians working, those Syrians who are working do not all have permits. Among employed Syrian refugees, only 43% hold a work permit (Figure 2).

While the majority of refugees (73%) with formal employment (with contracts or social insurance) have permits, there are still those who do not. The refugees with informal employment only have permits around two fifths of the time (40%).

Costs and benefits of work permits for refugees

For employed refugees, links between work permits and work conditions are important. Work permits (theoretically) give refugees greater legal protections in the workplace, such as contracts and a minimum wage. Refugees perceive benefits particularly in terms of protection from deportation.

At the same time, the work permits that refugees receive typically tie them to a specific employer. This tie may leave them with little recourse when employment conditions are poor or deteriorate (Razzaz, 2017).

Work permits may bring additional costs to refugees. Syrians that work in any job outside the agricultural sector in Jordan are required to register for social security with their permits. Social security is deducted from the refugee’s salary despite the fact that refugees do not receive the benefits of social security in return.

In addition, Syrian refugees worry that registering to work will cause a loss in their other aid benefits such as food and cash assistance, despite informational campaigns to explain otherwise (Razzaz, 2017).

Long-term plans for Syrian refugees’ work

The low employment rates of Syrian refugees and the low take-up of work permits are worrying trends for the wellbeing of refugees. As the Syrian conflict drags on, work will be increasingly important for the refugees to meet their basic needs.

One possible solution to increase the proportion of refugees in the labour force and with legal protections would be to change the annual renewal of the permit to a more substantial increment of time.

Furthermore, additional protection must be set up to protect refugee workers against exploitation by employers. Permits should be universal and allow Syrians to transfer and navigate between jobs rather than require them to stay with a single employer.

Syrians do not receive any benefits from social security, so they should not have to pay for it. Efforts must also continue to make eligibility for both permits and aid clear for refugees, so they are do not forgo permits out of misplaced fears of losing aid.

Despite the challenges with the work permit programme, it is still an important policy to help Syrian refugees in Jordan. Other countries hosting Syrian refugees should consider implementing and expanding work permit programmes, learning from Jordan’s example.

Further reading

Kelberer, Victoria (2017) ‘The Work Permit Initiative for Syrian Refugees in Jordan: Implications for Policy and Practice’, Boston Consortium of Arab Region Studies Policy Paper.

Krafft, Caroline, Maia Sieverding, Colette Salemi and Caitlyn Keo (2018) ‘Syrian Refugees in Jordan: Demographics, Livelihoods, Education, and Health’, ERF Working Paper No. 1184.

Ministry of Labour Syrian Refugee Unit (2018) ‘Syrian Refugee Unit Work Permit Progress Report January 2018’, Amman, Jordan.

Razzaz, Susan (2017) ‘A Challenging Market Becomes More Challenging: Jordanian Workers, Migrant Workers, and Refugees’, Beirut: International Labour Organization.