In a nutshell

Today in Lebanon, political settlements cannot be reached based on political and economic resources that are readily at the disposal of elites; instead, those resources increasingly need to come from sources outside their control.

The result is a grand waiting game in the scramble for access to resources, during which the costs of delay are pushed onto the broader population; accelerating the search for settlements requires raising the cost of waiting – only this time for elites, not citizens.

Creative revision of how corruption and obstruction can be sanctioned, as well as a development paradigm to undermine clientelist dependencies at the local level, could help to break the gridlock.

More than three years into Lebanon’s crippling crisis, political elites are still failing to find consensus on many important decisions. Apart from protracted issues such as much-needed reforms to resolve the financial and economic crisis, the failure to agree on executive authorities – a new government and president – adds yet another dimension to the political stalemate. The costs of this protraction rise by the day, mostly for middle-class and vulnerable populations.

Certainly, compromise was always costly, particularly in recent decades. Lebanon’s rulers were never exactly fast or efficient in settling their disputes, especially on more complex issues. The two-year hiatus preceding the election of Michel Aoun as president in 2016 or the protracted trash crises exemplify how critical decisions can drag on for years.

Yet something substantial has changed in the way in which elites can reach compromise. For example, government formation periods came to take up more than 13 months on average, up from only two to 14 days up to 2005, leaving governments in increasingly long periods of caretaker functions. These governments, which were almost exclusively unity governments after 2005, became more polarised and excluded a number of parties after 2019.

Administrative and political outputs suffered too. For example, the number of laws enacted in parliament dropped by more than a third: from 67 in the year preceding the financial crash (August 2018 to 2019) to 41 in the year thereafter. In that way, governance indicators, measuring such features as the effectiveness of governments in taking decisions, came to downgrade Lebanon’s ranking vis-à-vis peer countries from about the 50th percentile in 2011 to the bottom ten in 2021.

What explains such increased intransigence in finding consensus? This article argues that the determinants of a political settlement – a succession of deals among powerful political elites on how to distribute political power and economic resources (or losses), thereby determining political outcomes such as reforms or government formations– have changed over time.

Today, settlements cannot be produced based on political and economic resources that are readily at the disposal of political elites. Instead, these resources need to come more and more from sources outside the control of elites whose benefits are uncertain to predict. The result is a grand waiting game in which the costs of delay are pushed on the broader population. Accelerating the search for settlements requires domestic and international actors to increase the cost of waiting – only this time for elites, not citizens.

The puzzle – why wait?

Settlements can consist of roughly two types of resources: economic and political. Until recently, settlements could largely be struck using economic resources, largely made possible by leveraging the public sector. The 2016 settlement is a salient example, where a series of business deals between the institutions and companies controlled by major elites paved the way for Michel Aoun’s election as president of the Republic and Saad Hariri to head incoming governments.

Today, however, the public sector is essentially broke and offers few opportunities for distributing such economic rents. No new highways are built, while state employment has become limited and its salaries unattractive.

Admittedly, the present-day issues are complex and require more than ‘tit for tat’. By itself, however, added complexity and limited resources should not prevent settlements from occurring. Common interests for stability of basic services should enable compromise eventually with the tools that elites have at their disposal. Put simply, delay is costly amid runaway inflation, money locked up in banks, and exacerbating shortages of social services.

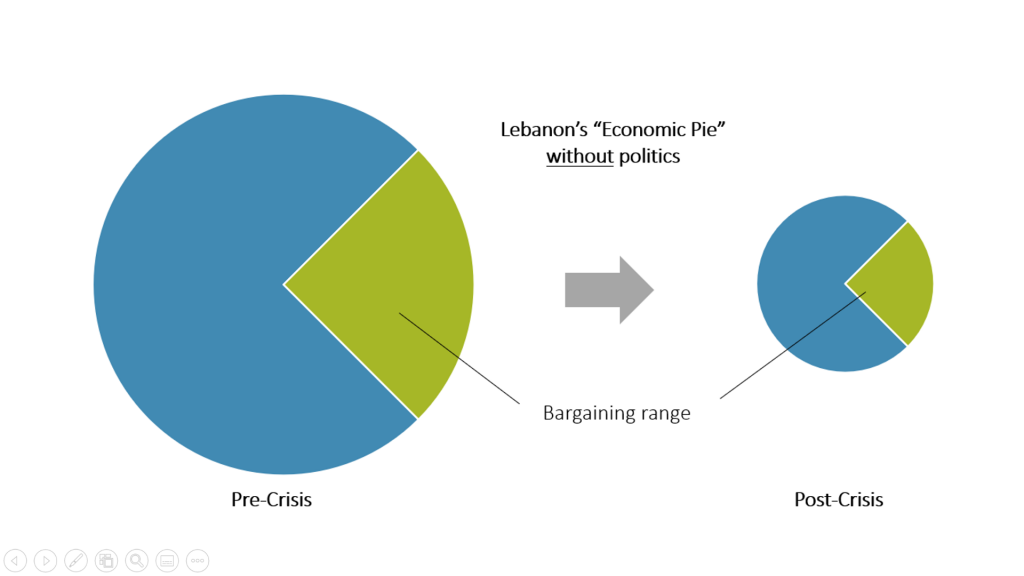

Imagine the economy as a pie. Part of the pie is composed of opportunities for elites to make or control economic rents (for example, taking control of infrastructure procurement projects). Being under direct control or influence of elites, this part of the pie can be used in negotiations to reach a settlement and can therefore called the bargaining range.

As the crisis has led to a significant contraction of the economy, the overall pie has shrunk. But if settlements were only about opportunities for economic rents, the bargaining range relative to the size of the pie would have essentially remained the same. It would still be in the interest of elites to have a share of a pie, and notably one that is larger, rather than smaller.

Granted, low trust between major elites, short-time horizons of governments amid political instability, exposure to the agendas of international actors, and the rush to find external guarantors make negotiations complex. Yet economic and political benefits from stabilisation and re-engagement of international donors provide significant incentives to compromise and let the pie grow again.

After three years of crisis, economic and political interests in economic policies (if ever they diverged) are now well defined and largely observable among all actors. Crisis-resolution measures are meanwhile well-understood and communicated in political and economic circles, all of which should enable a convergence on a minimum set of compromises in the common (if not public) interest.

In short, if bargaining was only about getting rich(er) from politics, settlements should still occur. Why, then, delay settlements even longer?

The paradigm shift

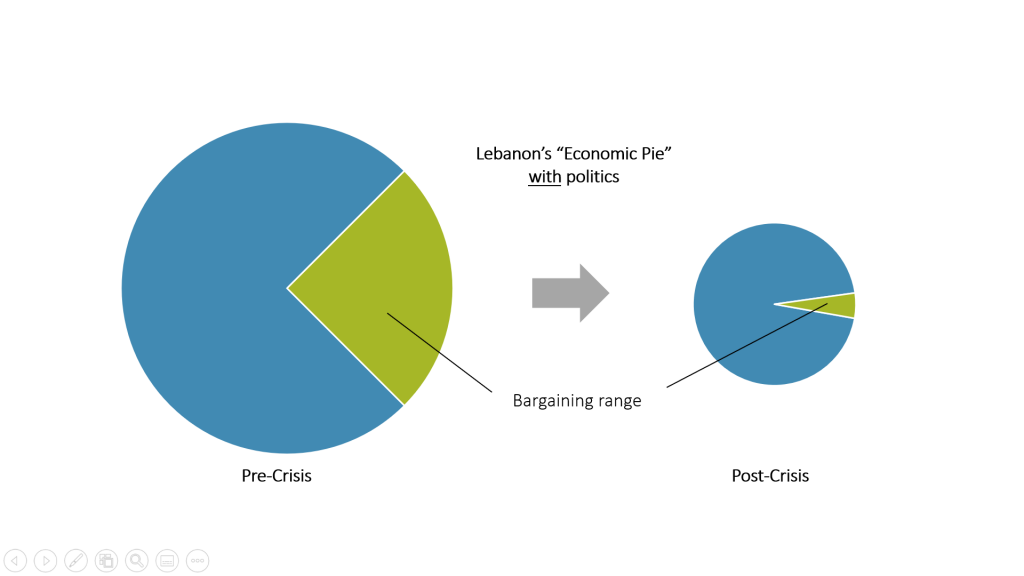

As economic resources provided by the public sector have dwindled over the course of the crisis, political resources have grown in value. But political resources are more complex to handle and less predictable. This diminishes the bargaining range of the pie.

One of the most important of these political resources today is polarisation. Polarisation became an end to itself, rather than a means to achieve something – an indivisible necessity for political survival.

To see why, consider the origins of polarisation. Polarisation doesn’t emanate from differences in policy preferences. Disagreement here is rather symbolic. When it comes to salient policy issues such as security, banking sector resolution, or the resistance to reforms for an IMF (International Monetary Fund) programme, virtually all parties have long shared the same views and interests.

Instead, polarisation increasingly emanates from the unfortunate development that being pro or contra Hezbollah, its mission or allies, has become one of the few political ideas that can lend legitimacy and broad support to a party. Maintaining polarising stances sends a costly signal, both to citizens at home and sponsors abroad, to take a party seriously and to continue supporting it.

The Lebanese Forces provide a salient example. After having been able to join governments with Hezbollah for decades, they staunchly oppose it today. This opposition provides the party with political capital that offers it a very raison d’être, securing increases in vote share and access to foreign resources notably from Saudi Arabia.

The Future Movement, by contrast, offers an example of what happens when elites fail to send such signals. In the absence of access either to domestic or foreign political and economic resources, the party eventually ceded in relevance and was forced to bow out. Political platforms trying to stay out of this debate, such as parties and parliamentarians emerging from the 2019 protest movement, face an uphill struggle for influence.

Herein lies the paradigm shift of elite-level contestation. As economic resources to fuel settlements dwindled amid the crisis and stalling international support, polarisation became a matter of political survival, superseding interests in the remaining available economic rents. This shrinks the bargaining range as elites have to find consensus on deals without compromise on (alleged) political opposition.

The grand waiting game

While the bargaining range still isn’t zero, such polarisation contributes to a strategic dilemma. Settlements need (some) support from the public, influential elites and their cronies. For decades, however, elites have kept expectations unreasonably high as to what the public pool of resources can promise as rents to cronies. Billions of dollars through infrastructure procurement, clientelism in public service, or the Ponzi scheme in the banking sector set the bar high of what to expect from settlements.

Today, such high expectations remain unmatched and adjust only slowly to new realities. Unreasonably strong narratives prevail that ‘deposits are sacred’ and the ‘money will come back’ with the help of the IMF or, more prominently, the proceeds from offshore gas exploration.

These narratives are simply unfounded. After three years of crisis and countless reports and papers, elites know that. So why cling to narratives that are so detrimental? Elites could start taming their language, adjust their public messaging to new realities and slowly wind down expectations.

The dilemma is that, at this point, elites’ best individual strategy is to wait in order to strengthen their bargaining position. As the internal, domestic pool of resources has become unattractive, future resources, most notably from gas exploration, are hailed from parties across the political spectrum as low-cost opportunities to resolve the current crises. Other developments in the banking sector too incentivise elites to wait. Inflation and the economic crisis pressure more and more depositors to liquidate their deposits, reducing pressure on the balance sheets of banks that are closely connected to political elites.

But gaining access to such resources will require time as proceeds from gas exploration, if ever they were to come, will take many years to flow into the coffers of state institutions. Elites and their parties must improve their bargaining position to ensure domestic and international support. This, in turn, requires polarisation.

Winding down expectations does not fit into this line of thinking. Maintaining expectations, instead, becomes a useful tool to buy time. Postponing settlements and thereby stabilisation is costly, yes. But the marginal loss today is negligible compared to the potential wins of accessing resources accruing in the future. The recent maritime border deal with Israel, for example, provides an important first step in this direction as the proceeds from gas exploration become an important new source of income to fuel the political machinery.

From the point of view of each party, moving first to ease polarisation or wind down expectations would weaken their bargaining position. Worst to bear, it could imperil their political survival. Plunging the majority of the population into poverty while crippling public services, then, becomes an unfortunate by-product of this grand waiting game.

The end game – and how to accelerate it

If a settlement remains unlikely for the time being, what is? Conflict, fortunately, isn’t. Despite occasional miscalculations, none of the ruling elites appears, at least for now, to have an interest in taking contestation to the streets and threatening violence. Moreover, notwithstanding the recent change of leadership in Israel, the maritime deal largely dissuaded threats of conflict at the southern border.

For the moment, waiting for the settlement(s) remains the game in town. The ability to distribute potential proceeds from future gas explorations appears to become one, maybe the major factor that determines how future settlements will look like. A much-needed IMF programme appears remote as ever. Absent stabilisation, public institutions will erode even more and thereby the government’s effectiveness to govern.

But waiting for the grand waiting game to end can mean changing the rules.

International actors in particular can play an important role to push for a settlement. Yet, they would have to adjust their approach. Past approaches based on large carrots, such as the CEDRE conference in 2018, promising many billions of dollars for infrastructure development in a sector cobbled with cronies in exchange for reforms, just don’t seem to work. Sticks might do better.

International actors can increase the ‘cost of waiting’ for elites in two ways. First, sanctions might offer tools that are not yet fully used. A creative revision of how corruption and obstruction can be sanctioned could help to break the gridlock.

Second, policy and programmatic approaches and priorities should be revised towards undermining clientelist dependencies at the local level – the bedrock of power for many elites. Independent and state-led local service providers, such as the Social Development Centers and others, must be strengthened in order to allow citizens to obtain services from the state as a right, not from political parties and affiliated NGOs as a favour. The IMPACT platform is another example of how support to households and individuals can be made impersonal and evidence-based.

Herein lie practicable pressure points in that elites would slowly cede influence as they play what they play best – the grand waiting game.

The author wishes to thank Sami Atallah and Sami Zougheib for inspiration, feedback and discussions.