In a nutshell

Resolving the region’s development challenges requires focusing first on the highly challenged countries: they face multifaceted challenges, and lag in all dimensions of quality-adjusted human development, environmental sustainability and governance.

Arab countries must recognise that without effective institutions, wellbeing cannot be ensured or sustained; at the same time, wellbeing is not a substitute for agency: both agency and wellbeing are essential aspects of human development.

Strong institutions should ensure that government effectiveness and democratic principles operate in a virtuous nexus; by the same token, democratic governance without quality public services is also not a solution.

The recently published World Development Challenges Report proposes a new global Development Challenges Index (DCI) to measure development from a broader perspective. The DCI adapts the global Human Development Index (HDI) to reflect the quality of human development achievements, which implies discounting HDI achievements by measures of quality.

But the report also goes well beyond that adjustment. Since a broader development measurement framework should entail integrating other dimensions, the report takes up two challenges of fundamental importance at all levels: environmental sustainability and governance.

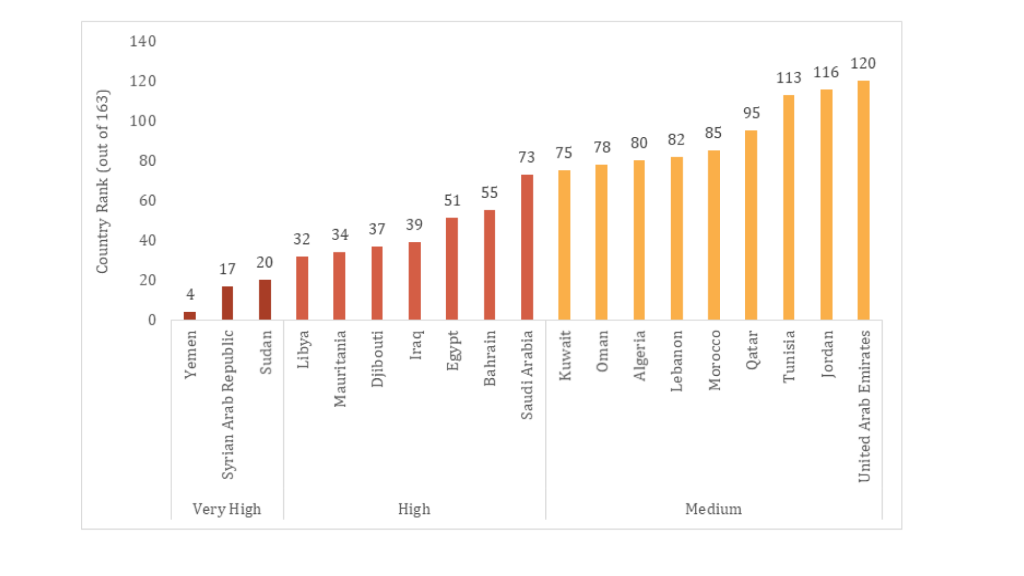

There are two main findings for Arab countries. First, and foremost, no Arab country has low or very low challenges. Of the 19 Arab countries assessed with the DCI, seven face high challenges (see Figure 1) with a population of 192 million individuals and three face very high development challenges with a population of 91 million individuals. They are home to nearly 283 million individuals or 70% of the Arab region’s population. The remaining nine countries are medium challenged with a population of 131 million individuals.

Where do Arab countries stand on the DCI?

Figure 1: DCI Arab country ranks (out of 163 countries), 2020

Source: ESCWA, 2022

Note: Ranks are in descending order of scores. Haiti, which has the highest DCI score, ranks 1st on the DCI is the most challenged country worldwide.

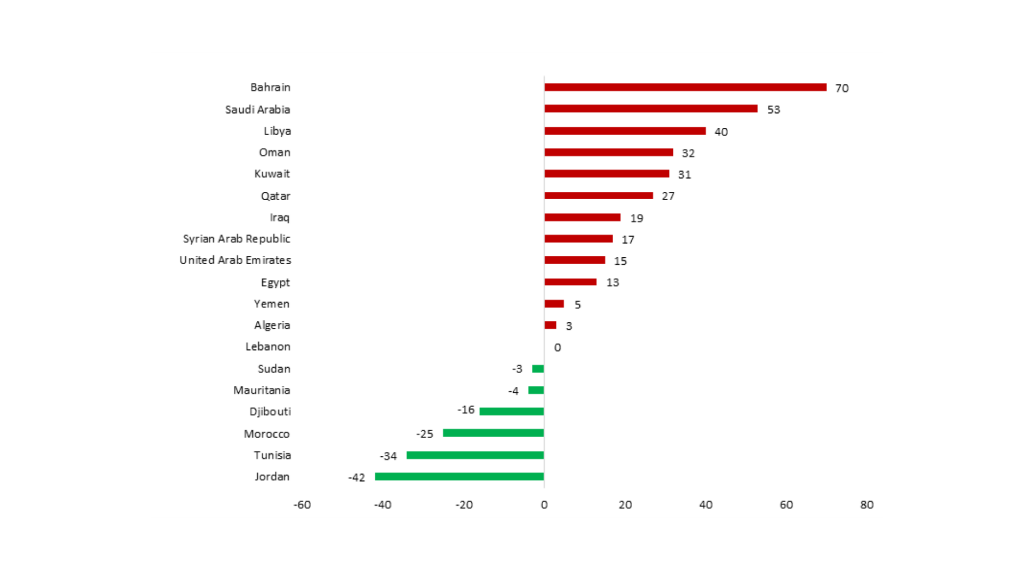

Given these results, an expected implication of our broader measurement framework for the regional narrative is that most Arab countries will incur significant rank losses on the DCI relative to the HDI or income per capita.

Figure 2 shows this clearly with five oil-rich Arab countries among the highest 20 rank losses globally on the DCI relative to the HDI. On the other hand, it is important to note that the DCI does not penalise all Arab countries. Three Arab countries, namely Jordan, Tunisia and Morocco, show significant rank gains.

Figure 2: Rank changes (out of 163 countries) when moving from HDI to the DCI ((1-DCI) – HDI)

Source: ESCWA, 2022

Note: Positive rank changes indicate a deterioration in rank on the DCI versus the HDI and vice versa.

Policy implications for Arab countries

These results reinforce the conventional wisdom that governance is the key development challenge facing Arab countries. Arguably, governance is also the underlying cause of other human development and sustainability challenges, which are highly interlinked with conflict.

Lower risks of conflict are more likely where policies create institutional and governance reform plans, close gaps between formal and actual rights, strengthen civil society’s capacity to hold dialogues with the authorities, develop strong political checks to protect accountability, and raise awareness of the importance of accountability in building public trust and confidence.

The most challenged countries in terms of agency are also the most highly affected by long-standing domestic and cross-border conflicts. Since conflict is strongly linked to governance systems and human rights, countries with weaknesses in these areas are at heightened risk of conflict. Good governance and respect for human rights and basic freedoms are vital to ending conflict.

Six other policy implications for Arab countries are supported by the findings of the World Development Challenges Report:

First, resolving the region’s development challenges requires focusing first on the highly challenged countries. They face multifaceted challenges, and lag in all dimensions of quality-adjusted human development, environmental sustainability and governance. Their vulnerability is reflected in stubbornly high extreme headcount poverty rates, which can exceed 45%.

Second, to provide support to highly challenged countries, the global community should implement measures similar to those provided to the least developed countries, including international tax cooperation to reduce tax evasion from multinational companies and to set standard wages to avoid inequalities.

Such measures should also consist of integrating capacity-development assistance for domestic tax revenue mobilisation, introducing global tax incentives to promote domestic processing, providing policy-making support, establishing a sustainable infrastructure fund, and developing cash transfer programmes.

Third, in today’s world of protracted conflict and violence, human security has assumed greater importance. Millions of people globally and in the region, especially in countries in the very high challenge and high challenge categories of DCI – such as Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen – have to cope with climate change, natural disasters, economic and health crises, and intolerance, instability and violence.

To ensure that no one is left behind, the emphasis should be on a deep understanding of threats, risks and crises, and of the interlinkages between human development and human security. To that end, countering the shock-driven response to global threats and promoting a culture of prevention are of utmost importance.

Fourth, although the Covid-19 pandemic caused new institutional challenges, it has pressured Arab countries to act swiftly amid increased uncertainty. Rapid changes in lifestyle and increases in non-communicable diseases have widened the gap between life expectancy and healthy life expectancy, which is now projected to exceed ten years globally.

Improving healthy life outcomes depends on protecting the health of environmental systems, which can only happen by adopting new technologies and by changing prevailing consumption patterns. Countries must therefore shift to more sustainable economic growth models that work for both the people and the planet. In the Arab region, for example, water consumption patterns will need to adjust to rising water scarcity.

Fifth, governments should focus on developing well-rounded and integrated educational systems that reach young men and women in all regions of a country, including the most vulnerable people in rural areas. Subsidies and scholarship programmes allow more students to complete their education and enter the labour market with required skills. This should also be matched with macroeconomic policies that aim to encourage decent job creation in order to preserve and reinforce the relationship between high-quality education, decent employment, and the reduction of poverty and inequality.

Last, as highlighted in the report, it is imperative for Arab countries to recognise that without effective institutions, wellbeing cannot be ensured or sustained. At the same time, wellbeing is not a substitute for agency. Both agency and wellbeing are essential aspects of human development.

Strong institutions should ensure that government effectiveness and democratic principles operate in a virtuous nexus. By the same token, democratic governance without quality public services is also not a solution. There is no inherent reason why wellbeing and agency should not play complementary roles. Arab governments should aim to advance both democracy and effectiveness.

Further reading

Abu-Ismail, K, V Hlasny, A Jaafar and others (2022) Development challenges index: statistical measurement and validity, ESCWA.

ESCWA, United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (2022) World Development Challenges Report: Development from a broader lens.