In a nutshell

The scarcity of essential foods in Gaza has been accompanied by a spike in prices; 90% of the population is experiencing high levels of acute food insecurity, with the same percentage of young children experiencing at least one disease as a result of extremely poor diets.

The West Bank labour force, which was previously dependent on jobs in Israel to generate around 15% of national income, have been barred from Israeli markets; a loss this size without any channels of employment to compensate could drive a fall of up to 29% in annual GDP.

The war has provided not only a smokescreen to accelerate efforts to change facts on the ground in the Gaza Strip, but also an opportunity to make the West Bank, including east Jerusalem, equally unlivable for Palestinians.

From the first days of Israel’s response to the Hamas attack on 7 October 2023 and beyond declared military goals, its official declarations made clear that Gaza should be flattened as military imperative required and that its inhabitants would be displaced from the north of the Strip. Some politicians went further and affirmed that Gaza should be made unlivable, indeed that only a second Nakba would be enough.

Some Israeli contingency planning has considered mass population displacement to northern Sinai as necessary to achieve war aims. Israeli and US diplomatic efforts have included trying to persuade Egypt and Arab states to facilitate such a move, under the humanitarian imperative.

Over six months of war, Gaza has given vivid meaning to concepts suggested by humanitarian organisations, such as ‘weaponising starvation’, ‘migration as a tool of war’ and ‘domicide’. The alarming declaration of ‘no electricity, no food, no fuel, everything is closed’ is now painted in gruelling and dark images of the humanitarian situation. Rarely has the threat of humanitarian disaster provided such a powerful sword to wield in an asymmetric conflict like this.

Many years of blockade on the Gaza Strip and its impacts on development had severely damaged the socio-economic conditions of its residents well before 2023. An Israeli obsession with demographics and the drive to exert control over the land by displacing its Palestinian population is now more evident than ever, particularly with the creation of ‘buffer zones’ and the looming threat of ‘relocation’ across the border, a plan that Egypt has refused on multiple occasions since October.

Israel aims to achieve this through two main tools: direct annihilation of Palestinians to ‘empty’ the space; and by forced displacement, either by intimidation and death threats or by the systematic destruction of infrastructure and other vital arrays of life. This cannot be observed in disconnection from long-term Israeli plans to displace Palestinians in Gaza, notably within the framework of the semi-official ‘Eiland Plan’ of 2004.

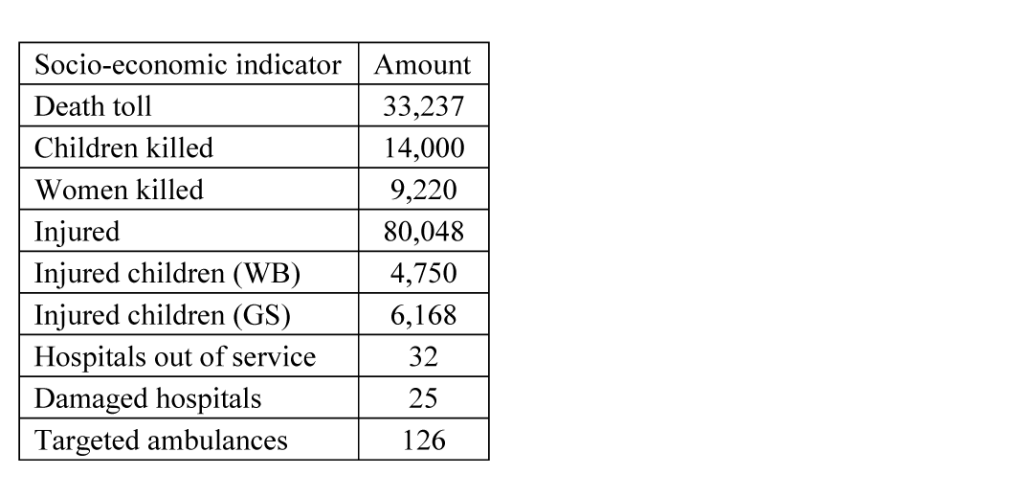

Satellite imagery monitoring the destruction of buildings in Gaza showcases the damage to or destruction of over 56% of buildings in the Strip. This wipe-out cannot be assessed in any way other than within the context of attempted erasure of Palestinians in the Gaza Strip, and Palestine as a whole. This is reflected in the large number of internally displaced persons (IDPs), which has surpassed two million, around 90% of the Gaza population, and the Israeli military has killed over 33,000 Palestinians in Gaza, including 14,000 children (see Table 1).

Table 1: Massive destruction in both human and infrastructural indicators of health in Gaza

The current aggression has led to dramatic demographic shifts, notably the dynamics between population and space: Israeli orders to displace residents from the North, which accounts for 20% of the area of Gaza, the destruction and damage of over 70% of buildings in northern Gaza, evacuation orders of 22 hospitals and over 2,000 patients, prevention of humanitarian aid, and direct targeting of individuals even during the seven-day ‘humanitarian truce’.

Now reaching southern parts of the Strip, Israel’s plan to displace Gazans and empty the area is inching closer, but it is being met with unprecedented resilience by the Palestinian people. Around 70% of the Strip’s population, amounting to 1.5 million IDPs, is now concentrated in the southernmost Rafah Governorate on the border with Egypt, facing the threat of forced mass displacement.

Starvation extends past being a weapon of war on its own, to also being an essential component of ‘migration as a weapon of war’. Factors such as relentless bombardment of agricultural territories, restricted access and severely limited influx of humanitarian aid have exacerbated the already dire levels of food insecurity to near-catastrophic proportions. Large portions of agricultural lands, orchards, greenhouses and farmlands have been systematically razed since Israel’s ground invasion, denying households 44% of their consumption of agricultural commodities.

The scarcity of essential foods has been accompanied by a spike in prices, dropping Gazans’ purchasing power by 25% in the first two months alone, while the consumer price index continues to surge in Gaza for the fourth consecutive month since the onset of the aggression.

As such, 90% of the population is experiencing ‘high levels of acute food insecurity’, with the same percentage of children under the age of five experiencing at least one disease as a result of extremely poor diets. An alarming 21 Palestinians including 17 children had perished as a result by early March, and the toll is rising daily.

Over half of the residents remaining in the North are suffering from catastrophic food shortages, while 15.6% of children under the age of two have become acutely malnourished. Additionally, grim accounts of Palestinians attacked while waiting for food trucks or airdrops underscore how aid is being used as a tool for wanton killing.

These pressures have built up against a pre-October backdrop of an Israeli government powered by extremist forces, which have for years been planning for the opportune moment to assert sovereignty in the West Bank. The minister of finance Belzalel Smotrich has been pursuing his 2017 three-stage ‘Decisive Plan’ to resolve the conflict in that part of the ‘Land of Israel’ between the river and the sea under the control of the State of Israel (as defined by the 2018 Israeli Nationality Law). In its detail, Palestinians may choose to submit to Israel, to ‘relocate’ to Arab or other countries, or to be dealt with by the Israeli military.

Since 2022, this plan has become the blueprint for Israel’s planning policy in the West Bank where Palestinians have faced unprecedented pressure from settlers, claiming more space, resources and control. Labelled as the most violent year for West Bank settlers, last year has witnessed at least 1,200 settler attacks, including 343 since 7 October, raising the monthly average from 21 to 35 attacks.

Over 1,500 Palestinians were displaced as over 1,000 structures were demolished, and similar numbers of people were displaced as a result of settler violence, while 26 new outposts were concurrently established in 2023, ten of which were initiated since 7 October. Since the war began, rebel Palestinian refugee camps throughout the West Bank have been targeted, and urban economic infrastructure in Jenin and Tulkarem bulldozed. Around 455 Palestinians were killed while over 7,500 have been arrested since then.

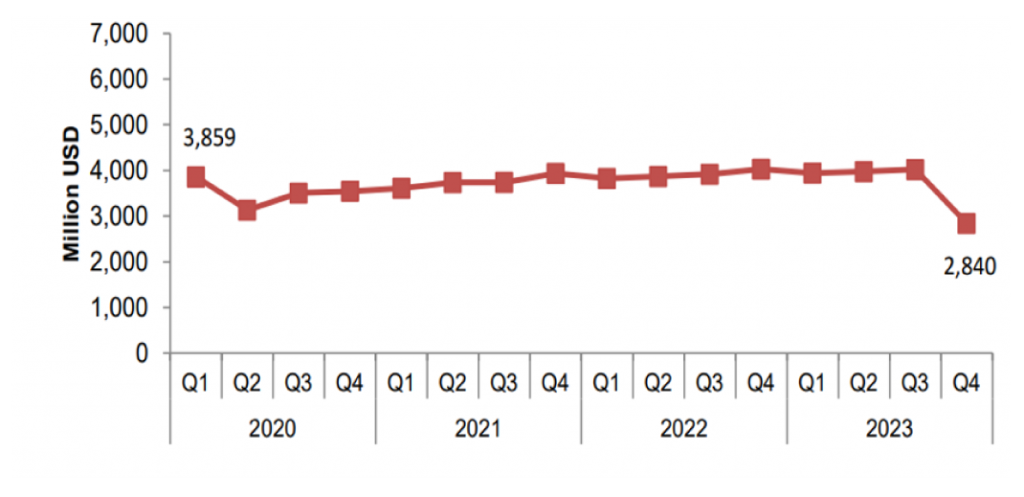

The first of the West Bank economic shocks came through the cut-off of income from labour in Israel for around 180,000 Palestinians, only tens of thousands of whom have since regained jobs in Israel. Its labour force, which was previously dependent on jobs in Israel to generate around 15% of national income, have been barred from Israeli markets since the war erupted.

A loss this size without any other channels of employment to compensate could be a driver on its own of a fall of up to 29% in annual GDP (see Figure 1). Meanwhile, Israeli restrictions on customs and trade tax revenues due to the Palestinian Authority, vital to sustain the government payroll and aggregate demand, have crippled the public treasury.

Figure 1: GDP at constant prices by quarter in Palestine has sharply declined in Q4 as a result of the war

Amid a police crackdown on individual and collective liberties in east Jerusalem, considered by Palestinians as their future capital, new settlement plans have been approved to extend Israelisation of the city demographically, politically and economically, while 350,000 Palestinians living there come increasingly under the tutelage of Israel.

The share of the east Jerusalem economy in that of Palestine as a whole has halved in the past three decades, with over half of its labour force dependent on jobs in Israeli markets, and around two-thirds of households classified as living below the Israeli poverty line. Jerusalem’s Palestinian economy sits in limbo between its historic links westward to the Arab hinterland and eastward toward skewed integration with the Israeli metropole.

The current war has provided not only a smokescreen to accelerate efforts to change facts on the ground in the Gaza Strip, but also an opportunity to make the West Bank, including east Jerusalem, equally unlivable for Palestinians. Palestine today faces an existential challenge, not only politically but in its very socio-economic fabric that goes beyond the realm of conventional analysis. As the Bob Dylan lyric goes, ‘you don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows’.

Further reading

Commission of Detainees Affairs (2024) Frequently updated numbers on Palestinian prisoners.

Decentralized Damage Mapping Group (2024) Conflict-Damage.

Defense for Children International (2024) ‘17 Palestinian Children Starve to Death in Gaza’.

MAS – Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute (2023a) ‘Preliminary Findings on the Impacts of the Cessation of Palestinian Labor in Israel on Key Palestinian Macroeconomic Indicators’, Gaza War Economy Brief No. 5.

MAS – Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute (2023b) ‘Forced Accelerated Demographic Transformation in Palestine: Learning from the Past to Understand the Present’, Gaza Way Economy Brief No. 8.

MAS – Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute (2024) ‘Palestinian Economy and Community in Jerusalem Facing Israeli Occupation Mounting Violations’, Gaza War Economy Brief No. 9.

MSF (2024) ‘Evacuation Orders and Forced Displacement Jeopardize People’s Health in Gaza’.

OCHA (2023) ‘West Bank Snapshot’.

Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (2023) ‘The Impact of the Israeli Occupation Aggression on the Agricultural Sector in Gaza Strip’.

Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (2024a) ‘Preliminary Estimates of Quarterly National Accounts (Fourth Quarter 2023)’.

Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (2024b) ‘Israeli Occupation Aggression on Palestine since Oct.7th 2023’.

Peace Now (2024) ‘A Good Year for Settlements; A Bad Year for Israel: A Summary of Settlement Activity in 2023’, Settlement Watch.

Security Council (2024) ‘Briefing on Food Security Risks in Gaza’.

WFP – Palestine Emergency Response (2024) ‘Situation Report No. 15’.

World Health Organization (2024) ‘oPt Emergency Situation Update Issue 26’.