In a nutshell

Financial informality among formal firms can occur even among those with a bank account: this happens when they are discouraged from applying for a loan to finance investment.

Crowding out limits the supply of loans to firms with bank accounts; and support schemes that operate via the formal credit market may have difficulties reaching firms that remain financially informal.

Reform of the business environment and improvements in managerial skills, which in turn increase the opportunity costs of remaining unbanked, are complementary to traditional interventions aimed at increasing the supply of credit.

Informality is widely recognised as a key factor limiting growth in developing countries. But recent empirical evidence shows that firms may reap limited benefits from formalising themselves. One of the main advantages of formality is better access to finance.

Nevertheless, this advantage is worth little if registered firms remain disconnected from formal credit markets. These firms are less likely to exploit the investment and growth opportunities that come with access to credit. In a recent study, we find that this is very common among small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) operating in Egypt. We refer to this state as financial informality among formal firms.

Financial informality can take at least two forms. The first form is that firms may refrain from having a saving or checking account, and instead rely solely on cash transactions. That in turn can gravely limit their access to the formal financial system.

Having a checking account is important for access to finance because it allows a bank to monitor inflows and outflows, and thereby reduces the information asymmetries that plague lending to small firms. In particular, account information helps the bank to establish reliable turnover and cash flow figures, which in turn is crucial for creating rudimentary financial statements.

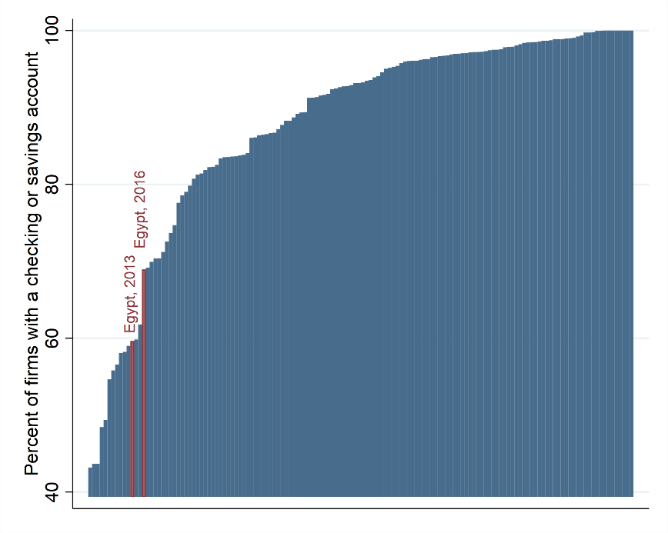

Figure 1 shows that being unbanked is widespread among Egyptian firms. Only 60% of firms had a checking or saving account in 2013, with the proportion increasing to 69% by 2016.

Figure 1. Account penetration in Egypt and around the world, by country

Source: Enterprise Surveys.

Account penetration in Egypt is low, but the country is by no means an outlier. Countries with lower account penetration include Vietnam, Pakistan, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, to name just a few with large populations.

We find that having a bank account depends on the characteristics of senior managers. In particular, bringing in a more educated and more experienced chief executive raises a firm’s propensity to open a bank account. These results can be partly explained by financial literacy among managers.

But we also find that firms run by more educated managers are more likely to have a website, to innovate, and to have expansion plans. This suggests that organisational capital arising from managerial skills and experience can also support financial inclusion by raising the opportunity costs of remaining unbanked.

Appropriate policies include measures that enable a more dynamic private sector overall, such as low barriers to entry and a playing field that is not tilted in favour of politically connected firms. Education reform can also bring benefits over the longer term. In contrast to traditional interventions that seek to increase the supply of credit, such policies would work through the demand side of the market.

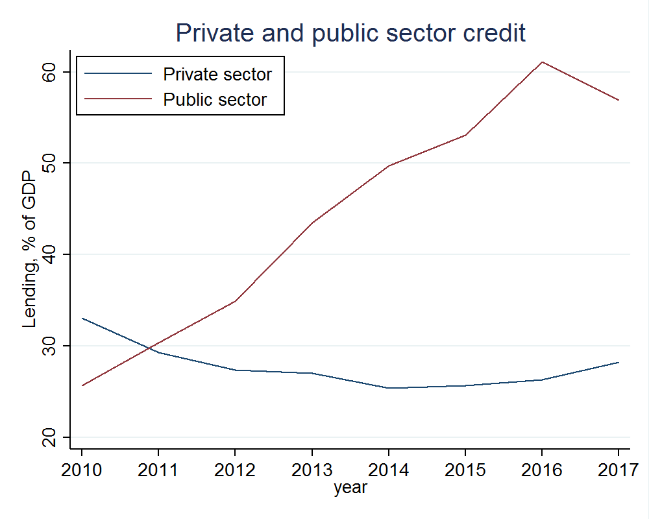

The second form of financial informality among formal firms can occur even among those with a bank account. This happens when they are discouraged from applying for a loan to finance investment. The decision not to rely on formal credit may be more likely if the intermediation capacity of the banking system is weak and the likelihood of being credit-rationed is high. We examine this hypothesis by studying the impact of the drastic increase in public debt between 2013 and 2016, which crowded out private lending to SMEs.

Figure 2 shows that the share of public debt in the balance sheets of banks increased substantially after 2011. But banks differ in the extent to which they accumulate government debt. Making use of data on the location of bank branches in Egypt, we find that firms become more exposed to crowding out when they are located near to branches of banks that invest more heavily in government debt. The exposed firms become less likely to apply for bank loans when they need one due to an unexpected liquidity shock.

Figure 2. Government borrowing from local banks in Egypt, 2010-17

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Central Bank of Egypt.

It turns out that our results are mainly driven by public banks and their higher tendency to accumulate government debt. Publicly owned banks play an important role in credit markets of developing countries, accounting for 71% of total assets in Ethiopia, 67% in India, 61 % in China, and more than 40% in large Latin American countries such as Argentina and Brazil.

Publicly owned banks are particularly crucial in serving areas that are financially less developed. Given their importance, our results provide novel insights on the link between the intermediation capacity of the financial system and the limited demand for formal lending among registered firms.

This has important implications for the period of economic recovery following the outbreak of Covid-19. Public debt has increased sharply to cushion the negative impact of the pandemic on the economy. Higher refinancing needs combined with heightened risk aversion among investors may drive up interest rates and crowd out lending to the private sector.

The authorities need to take account of the implications for the intermediation capacity of the banking system and the financing conditions of the private sector:

- First, crowding out limits the supply of loans to firms with bank accounts.

- Second, support schemes that operate via the formal credit market may have difficulties reaching firms that remain financially informal.

Over the medium to longer term, policy-makers need to recognise that reform of the business environment and improvements in managerial skills, which in turn increase the opportunity costs of remaining unbanked, are complementary to traditional interventions aimed at increasing the supply of credit.

The opinions expressed in this column are those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Investment Bank.

This column was first published on GlobalDev.