In a nutshell

Concerns that the gains of economic prosperity in Egypt over the last 25 years have been distributed unequally across the country are well-founded.

There is significant variation in income inequality across Egyptian governorates and a clear increase in income inequality within regions since 1999.

The increase is mainly attributable to a concurrent decrease in the income shares of the bottom two quintiles of the income distribution and an increase in the top quintile’s share in most regions over the period from 1999 to 2015.

There is a widely accepted consensus that income distribution is a key aspect of inclusive growth, which undoubtedly reflects the welfare and standards of living in a country. Even more importantly, a more equitable distribution of income is included in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 10: reduce inequality within and among countries).

From a political perspective, increased unevenness in the distribution of income within a country is a source of instability that threatens social cohesion and peace. Research on inequality typically identifies a trade-off with economic efficiency. Accordingly, growth is associated with an ‘accepted’ level of income inequality, nonetheless, beyond that ‘optimal’ threshold, inequality induces distortions of various types (social, economic and ethical).

To understand disparities in the evolution of income distribution, more spatially disaggregate evidence is needed instead of the aggregate (national) evidence generally considered to date. Geographically disaggregate evidence offers more appropriate insights for the within-country pattern of income inequality and assists in the design of more effective policies for improving living standards across a nation. With reference to SDG 10, policies that reduce inequality and poverty are successful only if they manage to restrict income variation across regions.

Our recent study serves this purpose with evidence of income inequality convergence across Egyptian regions (Bournakis et al, 2020). We estimate the nature and speed of inequality convergence across 27 governorates of the largest MENA country over the period 1999-2015. We open up a new chapter in the inequality agenda, which, subject to data availability, can be extended to other Arab countries.

The case of Egypt consists of a paradox as the aggregate level of income inequality is relatively low and stable (Al-Shawarby et al, 2014), yet aggregate figures are likely to mask large inequalities at the regional level. Egypt has experienced rapid growth rates in per capita income over the last 20 years with an annual average close to 2.5% (World Bank Development Indicators, 2019).

Subsequently, it becomes vital to explore whether growth gains have been equally distributed across geographical entities. In a broader sense, our study employs a newly assembled data set from the Luxemburg Income Study (LIS) to address this research objective with the construction of regional inequality measures.

Specifically, we address two main questions: first, whether differences in inequality levels among regions are narrowing; and second, which are the most affected segments of income distribution across regions. We have three main findings:

- First, the average regional Gini index has seen an increase over the period 1999-2015. This trend is mainly attributed to an average regional increase of the top quintile and a slight decline in the share of the bottom 40%.

- Second, the poverty rate (that is, the share of the population that lives below 50% of the median income) has also increased.

- Third, the cross-sectional dispersion indicates a general decrease over time (except for the middle quintile), which implies convergence in income inequality.

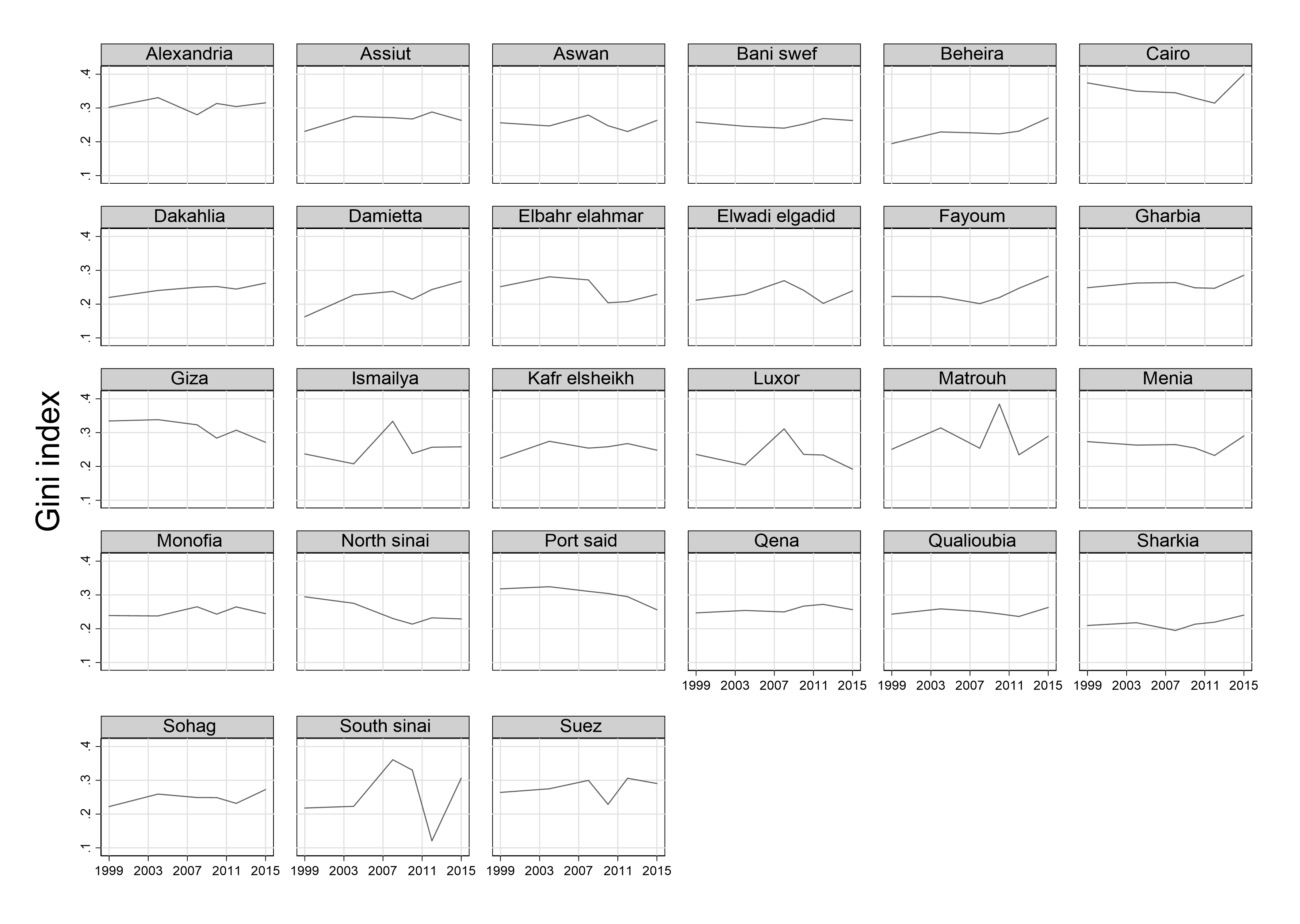

Figure 1 shows the trend of income inequality since 1999 for the 27 Egyptian governorates. There is a significant spatial territorial disparity with the most equal and unequal regions to be separated by a gap of 15 to 20 percentage points. Cairo maintains the highest level of income inequality (about 0.40 in 2015), while Sharkia shows the lowest level of inequality over time (between 0.21 and 0.24).

Figure 1: Gini Index (coefficient) for Egyptian governorates

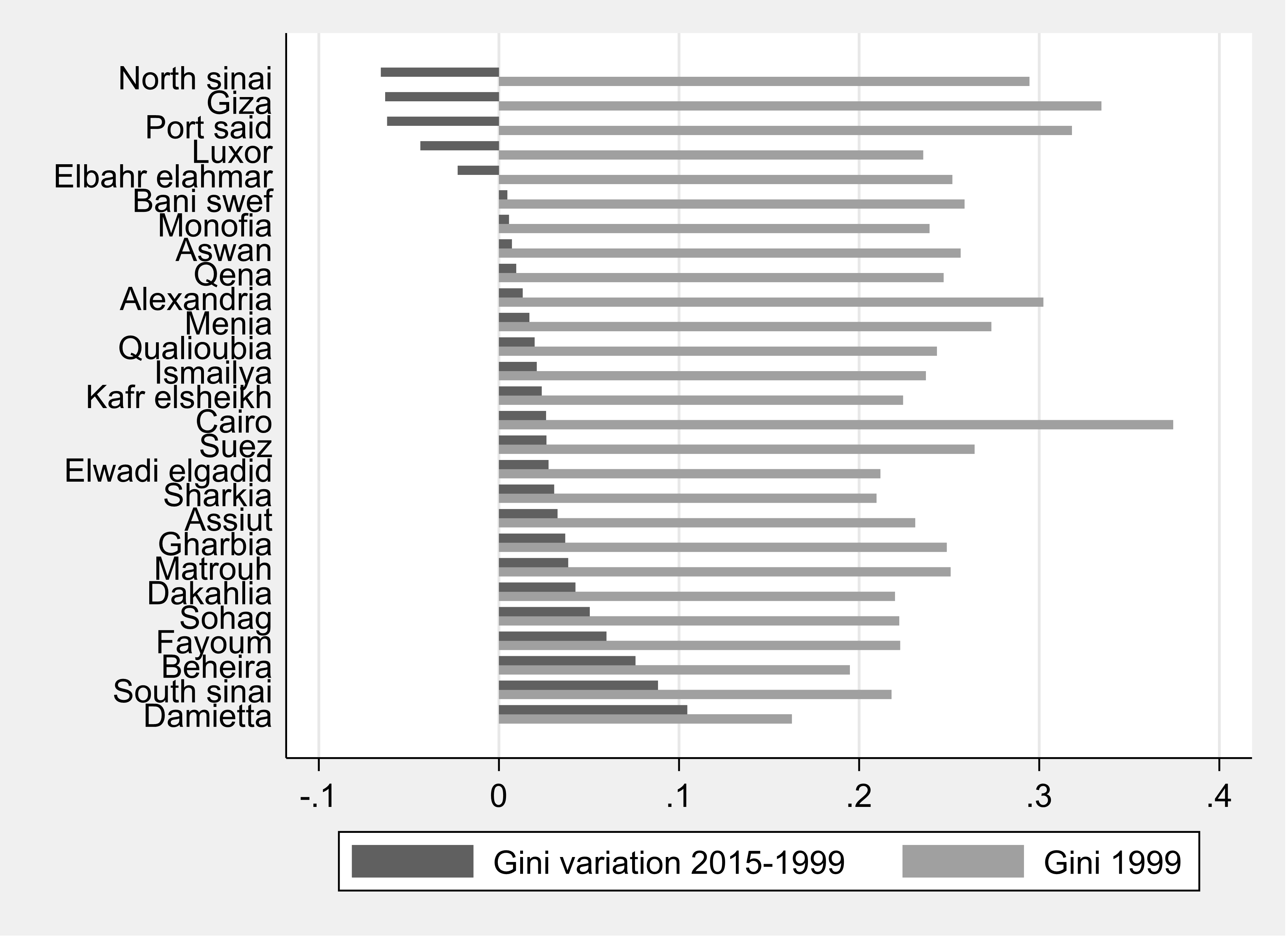

The evolution of income inequality is shown in Figure 2 with the value of Gini in 1999 (light grey bars) and the variation in Gini between 1999-2015 (dark grey bars). The chart indicates significant variation in income inequality across governorates and a clear increase in income inequality within regions since 1999. This is mainly attributable to a concurrent decrease in the income shares of the first two quintiles and to an increase in the top quintile’s share in most regions over the period 1999-2015.

Figure 2: Initial level of inequality and change over time: Gini 1999-2015

Our results represent estimates from unconditional convergence. This is to say that convergence in income inequality has occurred without controlling for other regional economic characteristics.

Although unconditional convergence in income inequality has occurred during the entire period, point estimates suggest that the speed of convergence is not always homogenous across different quantiles of the income distribution. The pace of convergence is relatively constant for the bottom 40% and the top quintile. The speed of convergence in the third and fourth quintile varies with intensity to be higher from 2010 onwards.

Overall, these findings point towards higher levels of inequality across Egyptian regions, which accord well with the notion that the political upheaval that led to the Arab Spring of 2011 was rooted, among other factors, in increasing income inequality.

It should be stressed that the pattern of relatively low income inequality in Egypt at the aggregate level is misleading, as the disaggregate evidence tells a rather different story. Therefore, concerns that the gains of economic prosperity in Egypt over the last 25 years were distributed unequally across the country are well-founded. Increasing inequality creates a feeling of injustice that should definitely attract the attention of economic policy-makers and government officials.

We do not cover the SDGs period, but one can safely extract conclusions that will be of relevance for Egypt’s performance in the period leading up to their adoption. The good news is that convergence has taken place in the first and second quintiles, so Egypt starts from an advantageous position with respect to Target 10.1 of the SDG 10.

Convergence suggests that the income growth rates of the bottom 40% have been greater in the regions where the first two quintiles had smaller shares. This trend should be maintained during the SDGs period to bring future progress on this target at both the national and regional level.

Similarly, convergence in the poverty rate suggests that progress on Target 10.2 in SDG 10 has also tended to become more geographically even during the period 1999-2015. More systematic monitoring of this trend is required during the SDGs period.

Further reading

Al-Shawarby, Sherine, Sahar El Tawila, Enas Ali A El-Majeed, May Gadallah, Branko Milanovic and Paolo Verme (2014) Inside inequality in the Arab Republic of Egypt: Facts and perceptions across people, time, and space, World Bank.

Bournakis, I, M Said, A Savoia and F Savoia (2020) ‘Patterns of regional income inequality in Egypt: Implications for Sustainable Development Goal 10’, ERF Working Paper No. 1400.

Dabla-Norris E, K Kochhar, N Suphaphiphat, F Ricka and E Tsounta (2015) ‘Causes and consequences of income inequality: A global perspective’, International Monetary Fund staff discussion note No. 15/13.

Klasen, S (2008) ‘The Efficiency of Equity’, Review of Political Economy 20(2): 257-74.

Wilkinson, RG, and K Pickett (2009) The Spirit Level, Allen Lane.