In a nutshell

The implications of a full-blown US-China or US-EU trade war are not limited to the main parties involved, but they also affect other third-party countries through overlapping trade and financial networks, thus disrupting global supply chains.

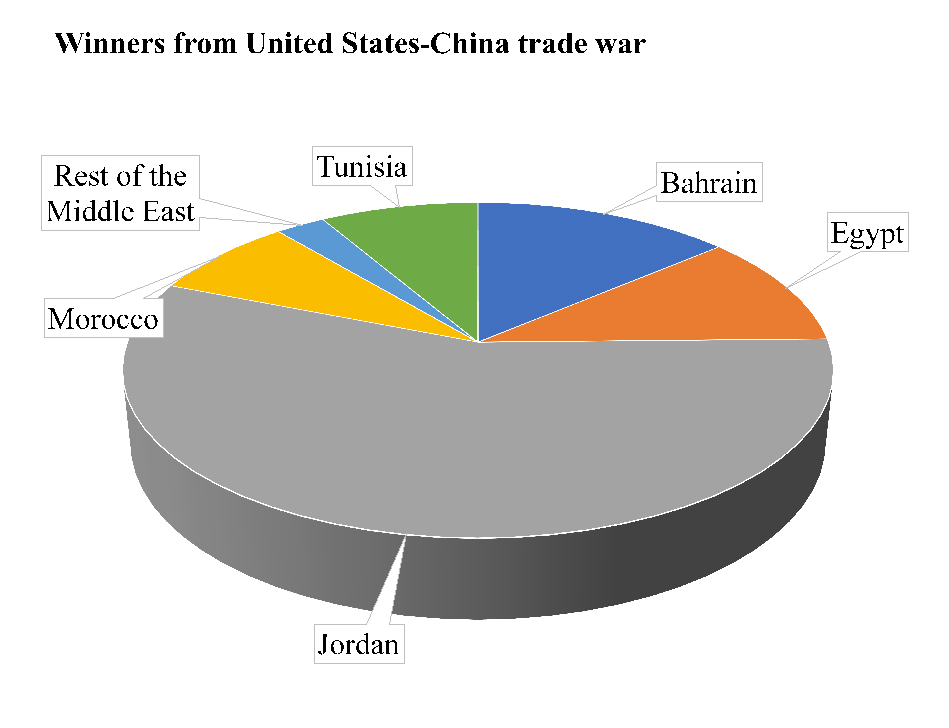

The primary winner in the Arab region from a US-China trade war is Jordan, followed by Bahrain, Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, and the remaining West Asian economies; oil-exporting countries are losers, notably Oman, Kuwait, Qatar and Saudi Arabia.

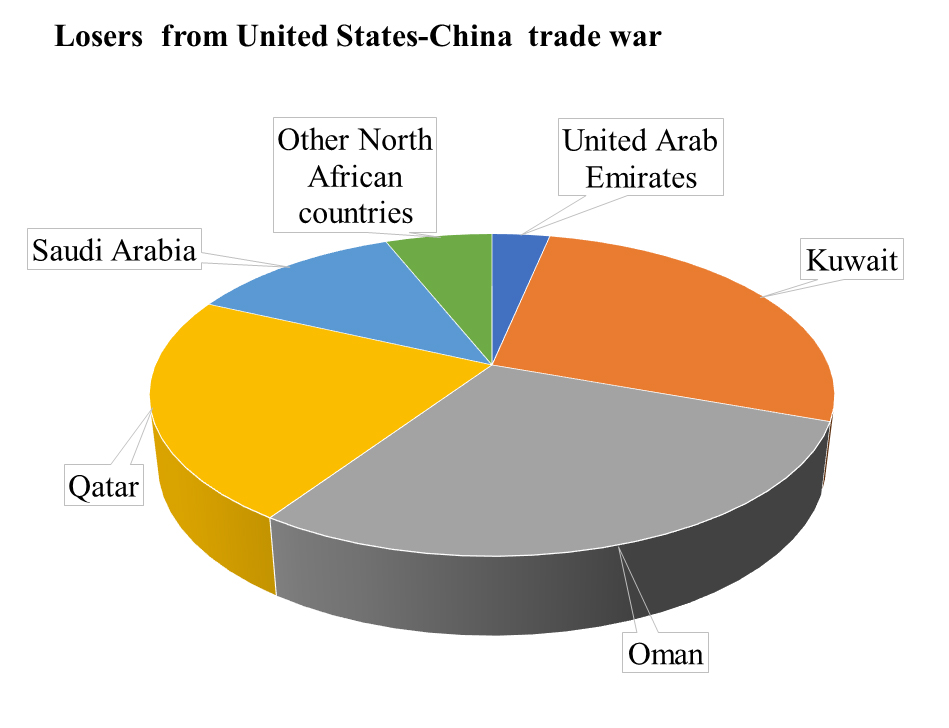

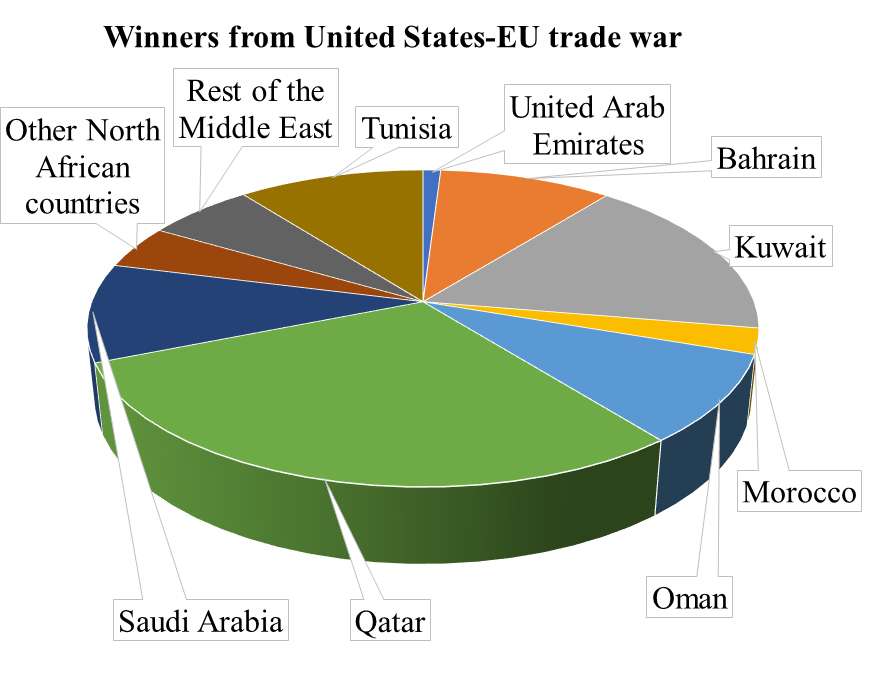

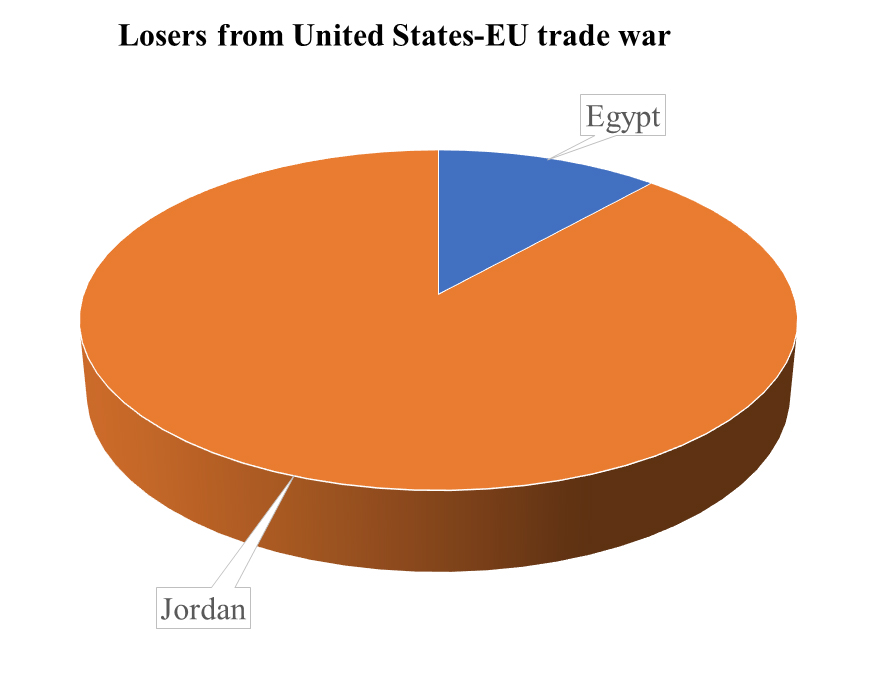

In the event of a US-EU trade war, except for Egypt and Jordan, all Arab economies benefit but to a different extent: Qatar followed by Kuwait, Tunisia, Saudi Arabia and Bahrain are the main winners.

The Covid-19 pandemic has revealed the vulnerability of global models of growth and trade to public health crises – and illustrated the speed with which such crises can spread and overwhelm cities, countries and the globe in our era of close connectivity. Indeed, in a sense, the integration of economies and the increased mobility of people and goods without matching integration of institutions and responses to potential threats has exacerbated the spread of this virus.

The true impact in terms of lives, livelihood and forgone economic activity is yet to be felt. But preliminary impacts and modeled outcomes reveal that the Arab region will lose $42 billion in 2020 due to the pandemic, although this may rise due to a further global economic slowdown and the effect of falling oil prices (ESCWA, 2020).

The pandemic comes at the time when the global economy is already suffering from trade tensions between the major global economic players: the United States, China and the European Union (EU).

Following his inauguration in December 2016, President Trump has pursued his campaign pledge to ‘Make America Great Again’ through protectionist policies and tax incentives for US corporations operating overseas aimed at bringing them back home. In turn, protectionism and tariff hikes have ignited trade tensions as targeted countries – mainly China and the EU – have retaliated by imposing equivalent tariffs on US exports.

Trade wars jeopardise world economic growth by disrupting global supply chains, and invite uncertainty for financial markets. This is particularly true when a trade war does not only affect two warring trading partners via tariff pass-through, but also through second-round spillover effects on economies of non-participating countries, mainly affecting trade and foreign direct investment.

But the level and austerity of a second-round effect hinges on economic structure and a country’s level of economic integration in the global economy. To that end, there is no one-size-fits-all effect for all countries. Some countries are severely affected by trade wars; other relatively closed economies are affected to a lesser extent; while others benefit from a trade diversion channel.

Given that many Arab economies are oil-dependent in terms of income and exports, either directly as in the case of oil-exporting countries or indirectly through foreign direct investment and remittances from oil-exporting to non-oil-exporting countries, all Arab economies are at the forefront of countries affected by trade wars. This is why as trade tensions have escalated since March 2018, oil prices have fallen, despite supply shocks arising from the Iranian and Venezuelan oil embargos, reaching $55 per barrel in August 2019 from $68 per barrel in May 2018.

Moreover, non-oil-exporting Arab countries, such as Jordan, Lebanon and Tunisia, are likely to suffer from tighter global growth perspectives. But they may benefit to some extent from increased exports to both the US and Chinese markets as a result of trade diversions.

This column summarises the major findings of an ESCWA study that estimates the impacts of the trade war on selected Arab countries using a global dynamic CGE model (Chemingui and Badra, 2019).

We constructed the model to assess the impact of trade war scenarios on a set of Arab countries. The analysis considers 10 Arab countries (Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Tunisia and the six countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council, GCC) and two Arab sub-regions: the remaining North African countries (Algeria and Libya); and the rest of the Middle East (Iraq, Lebanon, the State of Palestine, the Syrian Arab Republic and Yemen).

The model also considers the main economic players: the EU; the United States; China; and the rest of the world. Policy scenarios are compared to a baseline: a ‘business-as-usual’ scenario for a five year-period, 2019-2023.

Four scenarios are tested in the original analysis but the results of only two of them are presented here:

- Scenario 1: High US-China trade war: the assumptions under this scenario include changes in US-China tariffs in addition to new tariff increases that came into effect in September 2019.

- Scenario 2: High US-EU trade war: this scenario assumes a deterioration in trade regulations between the United States and the EU. It is based on President Trump’s declarations to increase significantly tariffs on selected imports from the EU. This scenario assumes the tariff changes already implemented by both parties until October 2019. In addition, it assumes the imposition of a 20% tariff by the United States on its imports of motor vehicles from the EU.

It is important to highlight that the second scenario is not yet implemented by the United States. Nevertheless, the US administration decided in October 2019 to implement higher tariffs on selected imports from four EU countries (France, Germany, Spain and the UK). But all changes decided after September 2019 are not included in the present assessment.

Macroeconomic impacts

To summarise the winners and losers from these trade war scenarios, Arab economies are divided into two groups (losers and winners) under the high US-China and high US-EU scenarios, reflecting the effect of the scenarios on overall country-level outputs. It should be noted that the transmission mechanism and the underlying channels through which an external shock, a trade war shock in this case, propagates in an economy hinges on a set of overlapping variables that differ between countries It depends on their initial situation in terms of productive structure, fiscal policy, trade policy, labour market and trade structure, among other factors.

Figure 1 summarises country level gains and losses in terms of real GDP under the high US-China scenario. The primary winner from the high US-China scenario is Jordan, registering 56% of the winners’ share, followed by Bahrain, Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, and the remaining West Asian economies with 13.8%, 10.9%, 8.4%, 7.9%, and 2.7% shares, respectively.

In contrast, oil-exporting countries are losers under the high US-China trade war scenario, with Oman, Kuwait, Qatar and Saudi Arabia comprising 28.8%, 27.3%, 22.5% and 12% shares of the total losses, respectively. This is mainly due to the oil demand shock mechanism arising from sluggish global growth, and thereby, reducing oil exports from oil-exporting countries. This in turn affects oil-exporting countries’ fiscal expenditures and investments, as oil receipts constitute the backbone of these countries’ fiscal revenues.

By the same token, oil prices affect stock markets in GCC economies, thus amplifying the effect of an oil price shock. In addition, as China devaluates its currency, imports of most Arab countries from China increase, because Chinese imports are now cheaper. The remaining Arab countries in Africa also lose from a US-China trade war scenario, constituting 6% of the share of total losses.

Figure 1: Winners and losers of the high US-China trade war scenario

Source: Chemingui and Badra (2019).

In the high US-EU scenario, except for Egypt and Jordan, all Arab economies benefit but to a different extent. Qatar followed by Kuwait, Tunisia, Saudi Arabia and Bahrain are the main winners, with 29%, 16.9%, 10.5%, 10.1%, and 9.8% of the winners share, respectively. Maghreb economies are more diversified, so a US-EU trade war would benefit these countries through a trade diversion channel. Oil-exporting countries also win from a US-EU trade war as the EU halts its energy imports from the United States and substitutes from other sources.

Egypt and Jordan, in contrast, would suffer most in the case of a US-EU trade war. The remaining North African countries and West Asian countries register 4.4% and 6% of the winners’ share, respectively.

Emerging markets are the first to experience a cut-off in financing as investors fear that weak financial and legal institutions are unable to cope with the new global business environment. Countries running internal and/or external deficits (Egypt, Jordan and Tunisia) are more affected as they struggle to finance their deficit in tighter financial conditions. This constitutes another indirect channel through which a trade war can affect Arab economies.

Tighter financial global conditions usually trigger a balance of payment crisis similar to the 1995 Mexican crisis and the recent Egyptian currency crisis, or leads to a sovereign debt crisis as emerging economies find it hard to roll over their debt or maintain their current external deficit.

Figure 2: Winners and losers of the high US-EU trade war scenario

Source: Chemingui and Badra (2019).

Conclusions

The implications of a full-blown US-China or US-EU trade war are not limited to the main parties involved, but they also affect other third-party countries through overlapping trade and financial networks, thus disrupting global supply chains.

Our findings document real GDP losses at the global level under both the US-China and US-EU trade war scenarios. In the case of a US-China trade war, China would lose more in terms of GDP, while the United States would lose more in terms of exports. Arab countries, as an economic bloc, would also suffer real GDP loses despite marginal improvements in exports under the US-China scenario.

Under the US-EU scenarios, Arab countries would register marginal developments in terms of real GDP and exports. At the country level, oil-exporting countries are key winners in terms of growth and exports; while Egypt and Jordan are the main losers in terms of GDP growth and total exports.

In summary, US trade tensions with the EU and China would not reduce the overall US trade deficit, despite possible bilateral trade balance shifts. The US trade deficit emanates from a high per capita consumption financed through high borrowing in international markets. On the contrary, trade tensions and possible trade wars disrupt global supply chains and boosts uncertainty.

Trade wars also have a ‘ripple effect’ on other countries, including emerging economies. Consequently, Arab countries are affected via two main channels: lower oil prices affecting oil-exporting countries; and changes in market access to global markets. But reducing US imports from China and/or from the EU would give opportunities to other countries worldwide, including some Arab countries, mainly non-oil countries to boost their exports and benefit from trade diversion.

China will certainly further depreciate its currency to increase its competitiveness and to offset the effects of higher tariffs. This additional competitiveness of Chinese exports will boost its exports to the rest of the world in general, including Arab countries. All these developments in an ever-changing global economy require specific policies to improve the competitiveness of Arab exports, mitigate potential costs and increase benefits.

Further reading

Chemingui, M, and N Badra (2019) ‘Global trade tensions: winners and losers in the Arab region’.

ESCWA (2020) Socioeconomic Impact of COVID-19: Policy Briefs.