In a nutshell

The dynamics of conflict in the Arab region are particularly daunting given that the actors involved are unusually fragmented, making peace negotiations or humanitarian development action extremely difficult, if not impossible, in many countries.

The authoritarian legacy of most Arab countries in conflict has undermined the development of a vibrant and active civil society that could facilitate reconciliation and the provision of humanitarian and development assistance.

The prospects for reconciliation and peaceful transition remain bleak for many conflicts in the region: a likely scenario is that many tensions remain unresolved and there will be sporadic episodes of intense violence.

The Arab region has been seriously affected by numerous longstanding conflicts, including the seven-decade occupation by Israel of the occupied Palestinian territory and other Arab territories, the Lebanese civil war and three major wars in the Arabian Gulf: the Iran-Iraq war of 1980-88; the invasion of Kuwait by Iraq in 1990-91; and the invasion of Iraq by the United States in 2003.

But since the onset of Arab uprisings in 2011, violence in the region has intensified and regional states are increasingly embroiled in domestic and cross-border conflicts spurred on by complex geopolitical conflict drivers, including governance deficits, human rights abuses, and struggles over identity and the control of scarce resources.

These conflicts have had a devastating impact, giving rise to illegal migration flows and increased poverty. As of January 2021, 60.8 million people in seven conflict-affected states are in need of some form of humanitarian assistance (according to calculations by the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia, ESCWA, on the basis of data contained in the 2021 Humanitarian Response Plans for seven countries: Iraq, Libya, the state of Palestine, Somalia, Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic and Yemen).

In addition, two of the most significant global humanitarian crises are taking place in Syria and Yemen, both of which have witnessed a significant reduction in living standards and reversals in development that will affect multiple generations.

Conflict reversing human development

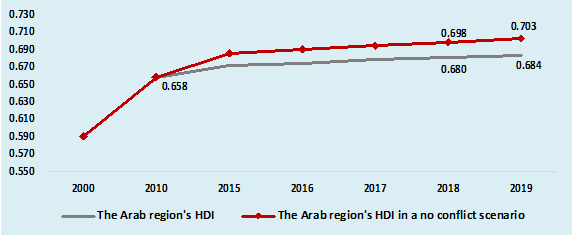

Conflicts have reversed many of the human development gains achieved in the early 2000s. Relative to a no-conflict scenario, the accumulated cost of conflict in Syria and Yemen amounts to a near 24% and 17.4% loss in their respective HDI (Human Development Index) values. Had those two countries remained on their pre-conflict development paths, Syria may now have been approaching the high HDI group while Yemen may have firmly established its position within the medium HDI group.

In fact, had all conflict-affected Arab countries maintained the pre-conflict human development trajectories 2000 and 2010, the Arab region might have achieved an HDI score of 0.7 in 2019, instead of an estimated 0.684 (see Figure 1).

Furthermore, conflicts and their repercussions are not confined to these countries. Multiple spillover effects have been recorded across the region. One such effect is the massive cross-border movement of refugees. In some countries, and especially in Lebanon and Jordan, those movements put enormous pressure on the host country’s economic and social infrastructure.

Figure 1: HDI for Arab countries 2000-19 and extrapolated HDI trends under pre-conflict scenarios for the period 2010-19

Source: ESCWA (2021)

Continuing conflicts and growing socio-economic challenges also pose a serious risk for the region’s prospects and put it at risk of further conflict in the near future. For example, the human hazard risk, which is calculated by assessing current conflict intensity and the probability of future conflict, captures the threat posed by the region’s high incidence of active violent conflicts.

Seven out of the 22 Arab countries fall within the ‘very high’ and ‘high’ risk categories for current violent conflict intensity, reflecting the continuing risk posed by the high incidence of violence and political instability. ‘Very high’ and ‘high’ risk countries are home to roughly 60% of the region’s total population. The high probability of future conflict, therefore, poses a significant risk for the Arab region.

A similar grim outlook is depicted when examining the projected conflict risk measured by the Global Conflict Risk Index, which assesses a country’s probability of experiencing violent conflict in the subsequent one to four years, taking into account a range of relevant political, security, social, economic and geographical/environment related factors that affect a country’s probability of conflict.

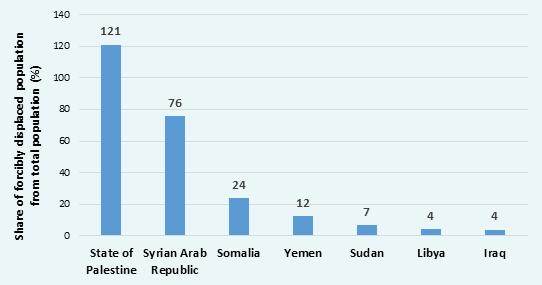

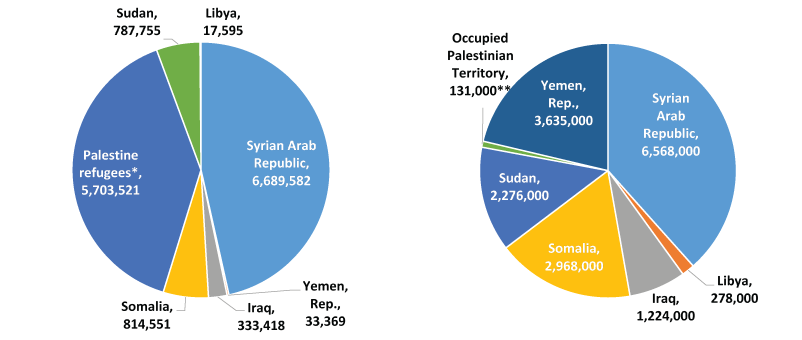

Particularly noteworthy is the projected conflict risk, which remains high in those seven countries. Also noteworthy is the catastrophic number of forcibly displaced people. Home to tens of millions of refugees and internally displaced persons, the Arab region is, in fact, at the epicentre of the world’s forced displacement crisis.

For example, in 2020, there were more than six million Syrian refugees, while roughly the same number of Syrians was internally displaced within their country. Needless to say, the high risks of conflict described above will impede the return of many forcibly displaced individuals to their homes.

The dynamics of conflict in the Arab region are particularly daunting given that the actors involved are unusually fragmented, making peace negotiations or humanitarian development action extremely difficult, if not impossible, in many countries. In addition, many violent non-state actors, including Al-Qaida and Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant, are driven by ‘exclusivist’ or ‘eliminationist’ ideologies. Reaching an understanding with such groups and their affiliates is often not possible.

Furthermore, atrocities and human rights abuses committed by any party to a conflict make an end to violence very difficult. Atrocities and abuses can, in fact, further radicalise armed parties and their followers.

Figure 2: Forcibly displaced persons in selected Arab conflict-affected countries, 2020

A) Number of refugees B) Number of internally displaced persons

C) Share of forcibly displaced persons from total population

Source: Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Global Trends in Forced Displacement in 2020 (UNHCR, 2020), United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA, 2020) and United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs World Population Prospects (DESA, 2020).

*Palestine refugees are persons and descendants of fathers whose ‘normal place of residence was Palestine during the period 1 June 1946 to 15 May 1948 and who lost both home and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 conflict.’

** IDPs (internally displaced persons) in the Occupied Palestinian Territory are displaced mainly within Gaza as a result of recurrent Israeli military escalations against the Strip.

The authoritarian legacy of most Arab countries in conflict has also undermined the development of a vibrant and active civil society that could facilitate reconciliation and the provision of humanitarian and development assistance.

More importantly, the collapse, fragmentation or weakness of state institutions has long-term security, humanitarian and development implications; populations in states in conflict have limited access to essential services, including security, while large areas fall outside the control of the state and may become fertile ground for the development of war economies and the trade in illicit goods.

Armed groups in those areas often fight among themselves for access to and control over resources and the civilian inhabitants of those areas are often subject to extortion by non-state actors and are at risk of falling victim to acts of terrorism.

Finally, geopolitics, particularly competition among international and regional powers, has historically exacerbated domestic conflict. This is of particular concern as foreign involvement in regional conflicts has, if anything, become more direct and overt over the last decade. A number of researchers recognise the determinative role that external factors can play in protracted conflict. Civil wars often end quickly once external patrons decide to end their support for local fighters.

The current conflicts in Libya, Syria and Yemen are cases in point. Foreign powers have used proxies as tools for their strategic goals, often at the expense of the wellbeing of local populations. Foreign-backed proxies have fought to promote a range of ideologies or to gain access to strategic rents that can sustain their local power structures.

The fragmentation of armed actors, exclusivist ideologies, human rights abuses, geopolitics and the weakness or absence of local peace assets, coupled with weak state institutions mean that the prospects for reconciliation and peaceful transition remain bleak. A likely scenario is that many tensions remain unresolved and there will be sporadic episodes of intense violence.

This column is drawn from a technical paper titled ‘Domestic conflict: a proposed index and its implications for Arab states’ by Khalid Abu-Ismail, Youssef Chaitani and Manuella Nehme, published by ESCWA.