In a nutshell

Egypt’s total population has doubled in the last 30 years – yet the share of the population living in urban areas has not changed.

Approximately 60% of Egypt’s population still live in rural areas; internal migration rates are very low relative to the global average.

International migration prospects are likely to have dampened internal migration in Egypt.

Egypt has experienced substantial population growth over the last few decades. The country’s population has doubled in 30 years and reached 100 million in 2019 (UNDP, 2019).

Yet the rate of urbanisation has hardly changed in Egypt over the past 50 years. Since 1970, the share of the population that is urban has remained around 43% (UNDP, 2018). Moreover, urbanisation in the rest of North Africa has substantially surpassed that in Egypt.

In 1950, Egypt was among the leading countries in North Africa in terms of urbanisation. In 2018, Egypt had the lowest urbanisation rate among other neighbouring North African countries, including Algeria, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia (David et al, 2019). The urbanisation rate in Egypt stands at 43%, while the rate in the other North African countries is close to or higher than 70%.

We explore the extent to which internal migration has been responsible for the slow urbanisation in Egypt. Furthermore, given the importance of international migration, we investigate the relationship between international migration and internal migration.

In David et al (2019), we examine the evolution of internal migration rates in Egypt by decade of migration, focusing on various types of mobility: mobility between regions, governorates, cities or towns (qism/markaz) and villages (shyakha). We show that internal migration rates have been very low in Egypt, and we also find suggestive evidence that internal migration rates have been declining over time, since the 1980s.

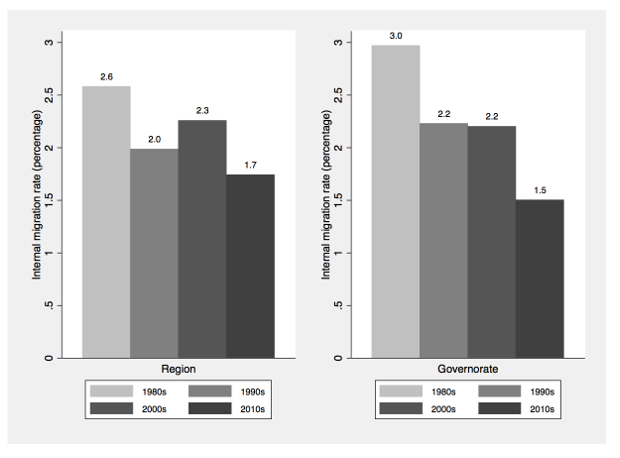

For example, the regional migration rate went down from 2.6% in the 1980s to 1.7% in 2010s. Similarly, the internal migration rate between governorates decreased in the 2010s to reach 1.5% relative to 3% in the 1980s (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Internal migration rates (percentage) by decade of migration, mobility between regions and governorates

Notes. This figure features internal migration rates by decades of migration. This figure features mobility between regions (left panel) and mobility between governorates (right panel).

Moreover, we find that rural-urban migration has remained very low and that similarly, it has witnessed a decline over time. Migration rates from urban to rural areas have been almost equal to rural to urban migration rates over the past few decades. Taking into account urban to rural migration explains the very low and stable urbanisation rate in Egypt.

While internal migration has been very low, Egypt has been experiencing a steady flow of temporary international emigration, predominantly to other Arab countries and particularly to the Gulf States. We find that in 2018, almost 2% of individuals between 15 and 59 years old were international migrants and 7% were return migrants.

Furthermore, when we consider the rates of international and return migration experiences at the household level, we find that in 2018, 11% of Egyptian households either have or had an international migrant. We also find that these rates were even higher in 2012, which is likely to be a reflection of the impact of more restrictive immigration policies in destination countries.

Given the low rate of internal migration relative to international migration in the broad picture of mobility in Egypt, we explore the relationship between internal and international migration. More specifically, we examine whether international and internal migration substitute or complement each other.

Indeed, we find that in both 2012 and 2018, less than 1% of individuals aged between 15 and 59 years old were both internal and return migrants. These figures suggest that most individuals who engage in either internal or international migration do so solely without engaging in both types of mobility. It is also worth noting that we find that in 2018, the share of individuals who migrated overseas and returned is higher than the share of individuals who moved internally.

Urbanisation is key for economic development. While most North African countries have made major advances in this respect in recent decades, Egypt is still lagging behind and urbanisation rates have been stagnant since 1970. We find evidence that the lack of urbanisation in Egypt is partly explained by very low internal migration rates and that international migration prospects are likely to have dampened internal migration in Egypt.

Further reading

David, Anda, Nelly El-Mallakh and Jackline Wahba (2019) ‘Internal versus International Migration: Together or Far Apart’, ERF Working Paper (forthcoming).

UNDP, United Nations (2019) World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.

UNDP, United Nations (2018) World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.