In a nutshell

Jordan has good statistical capacity and a nearly complete list of the indicators of progress on the sustainable development goals (SDGs).

Comparing Jordan’s current status of and progress on the SDGs, global, regional and national assessments are similar in some obvious cases (such as SDG 8 on employment and growth); but in many cases, they differ, at times significantly on important indicators (such as SDG 1 on poverty).

The SDGs are designed to be universal and they serve their global purpose well; but they should be used with caution at the country level, when national statistics are accurate and timely.

When it comes to statistics monitoring progress towards the sustainable development goals (SDGs), Jordan is among the world’s leaders. A Sustainable Development Unit at the country’s Department of Statistics (DOS) collects the 169 nationally adopted indicators, 102 from domestic sources and 67 from international sources. DOS has created a dedicated Jordan Development Portal that makes information on the SDGs available to the public.

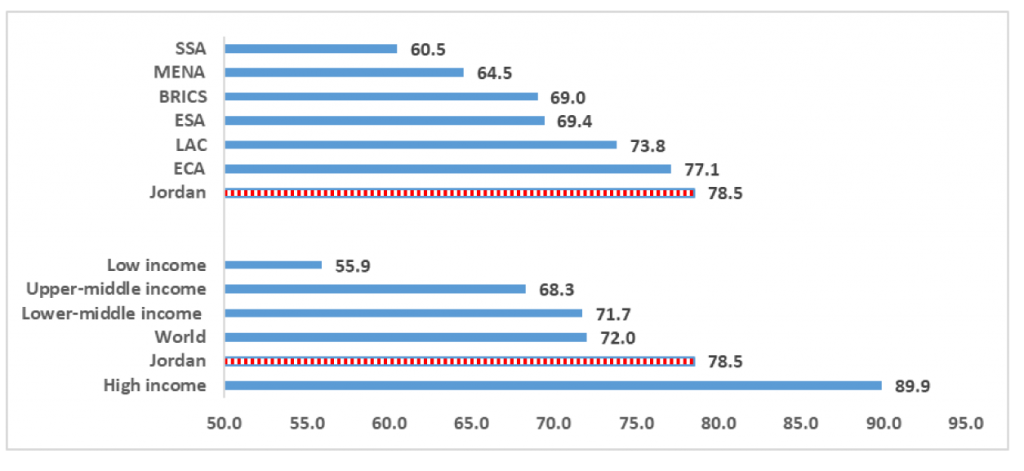

The United Nations (UN) Statistical Performance Index for the SDGs ranks Jordan only second to the group of high-income countries, and gives the country a score of over 79, which is 10% above the global average (see Figure 1, lower panel). Jordan exceeds the average score of all country regions and is 24% above the average score in MENA (upper panel). Among Arab countries, Jordan is practically on par with Egypt and by far above its neighbours Iraq (56), Lebanon (59), Syria (32) and Yemen (34), and the Maghreb countries, namely Tunisia (75), Morocco (72), Algeria (63) and Mauritania (59).

Figure 1: SDG statistical performance index (0-100)

Source: Sachs et al (2024).

Since assessments of progress towards the SDGs are primarily based on information provided by the relevant authorities in individual countries, regional and international assessments should show considerable uniformity with national assessments. Yet there are several significant discrepancies across the three assessments as we show in the case of Jordan, with the qualification that the cited years refer to when the assessments were published and they may not capture the current status and latest progress on the SDGs.

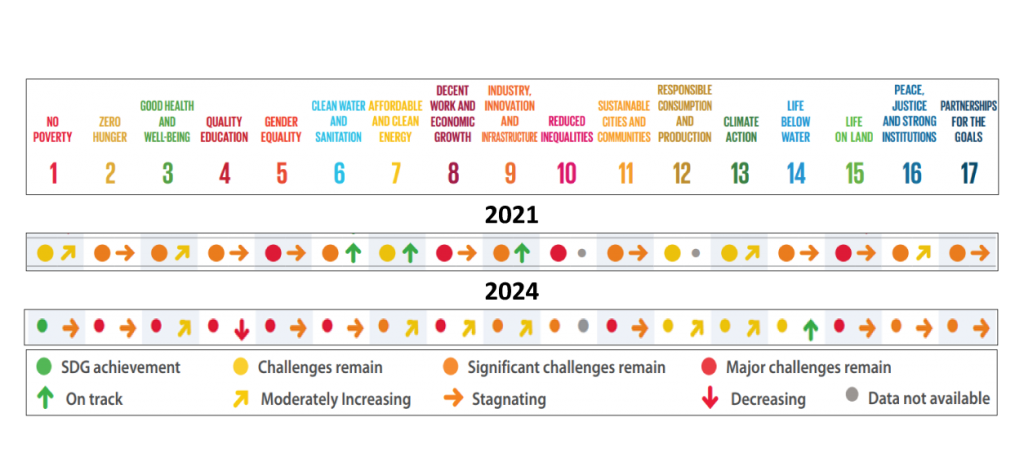

International assessments: 2021 and 2024

Noting the lack of data in Jordan for SDG 10 and SDG 12, a 2021 global review reported no missing information for the other SDGs. It found that Jordan had achieved none of SDGs by then, but was ‘on track’ with respect to three SDGs (6, 7 and 9) and had made moderate progress in another four (1, 3, 13 and 16). Among the remaining SDGs, none was assessed to be regressing (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Jordan: global assessment of status and progress towards the SDGs, 2021 and 2024

A different picture emerged in a short period of three years. By 2024, none of the three previously ‘on track’ SDGs were still on track. Rather unexpectedly, an important one was achieved (SDG 1 on poverty). A new one was added as being on track (SDG 14), referring to the narrow stretch of land in Aqaba (26 kilometres) along the coastline of the Red Sea.

All other SDGs were ‘moderately increasing’ or ‘stagnating’ except for SDG 4 on education, which was assessed as regressing. Four were facing ‘major challenges’ including the SDGs that have far-reaching effects such as those for hunger, health, sustainable cities and life on land. SDG 8 on economic growth and the labour market was noted as ‘moderately increasing’ although, according to national assessments, it has (at best) been moderately decreasing (see below).

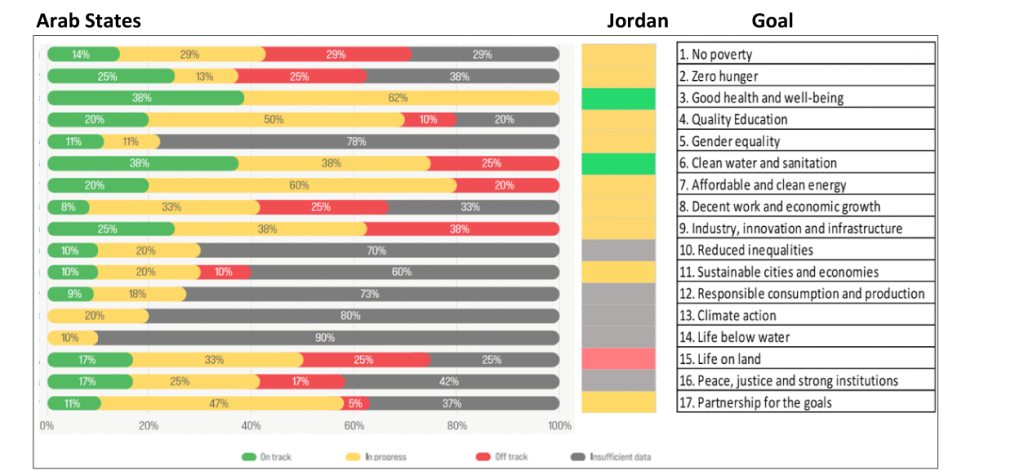

A regional assessment, 2023

Between the two dates of the global assessments, a regional assessment was carried out by the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) in 2023. Unlike the 2024 global assessment, which noted unavailability of data only for SDG 10 on inequality, ESCWA reported that Jordan has insufficient data for no fewer than five SDGs (see Figure 3). At variance with the 2024 global assessment, SDG 3 on health and SDG 6 on water were found to have been achieved.

Figure 3: Regional assessment of Jordan’s SDG progress, 2023 or latest

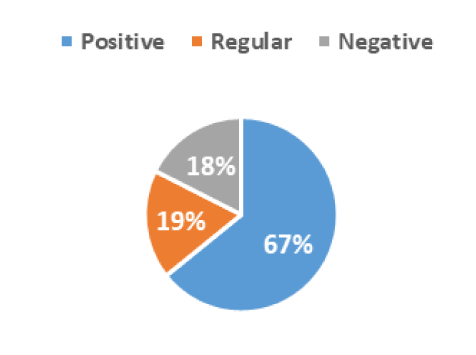

Domestic assessments, 2022 and 2023

The latest national assessment was presented in the Third Voluntary National Review (VNR2022). According to the review, Jordan has made progress on nearly 63% of the SDG indicators – a significant achievement (see Figure 4). Among the remaining indicators, 18% were regressing and the rest were reported as ‘regular’ (sic).

Figure 4: National assessment of progress in SDG indicators, 2022

The review noted most progress on SDG 9 (infrastructure and industry innovation), SDG 6 (clean water and sanitation), SDG 12 (responsible consumption and production), and SDG 14 (life under water). Least progress was reported for SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth) and SDG 10 (reduction in inequality). Another national report (Economic Modernization Vision 2023-33) reported that Jordan is at or below the fourth (lowest) global quartile with respect to foreign direct investment, quality of life and global knowledge, and in the third global quartile in terms of environmental performance, food security and social progress. These areas relate to most of the SDGs.

A selective comparison of the different assessments

There is agreement among the three assessments about SDG 8 on employment and growth. There is also agreement between the global and regional assessments that SDG 15 (life on land) is ‘off track’. But there are few similarities concerning many of the other SDGs. For example, the global assessment shows that SDG 3 on health is stagnating, while ESCWA reports it as being on track by 2030. This also is the case for SDG 6 on water, receiving a negative assessment in the global assessment but a positive one by ESCWA.

Most importantly, the change in the global assessment for poverty being already achieved in 2024 is puzzling (not least as it comes after Covid-19, if not post-Ukraine and post-Gaza for which statistical updates may not be available at the time of the assessment). In fact, there has been no new official estimate of poverty since 2017-18.

To the contrary, in 2022 the Minister of Planning and International Cooperation stated that the poverty rate had ‘temporarily’ reached 24%, attributing the increase to the impact of the pandemic. In 2023, ESCWA used proxy indicators to report that the poverty rate had reached 27%. A similar discrepancy applies to SDG 10 (on inequality), with the global assessment showing improvement but VNR2022 noting the opposite. ESCWA states that information on inequality is unavailable.

The global assessment gives SDG 5 on gender lowest marks and stagnating. ESCWA indicates that gender equality is ‘in progress’: this is more accurate as there have been several legal improvements, education achievements for girls and employment gains for women (relative to men) since the early 2010s and especially since 2018.

For example, maternity benefits are now financed by social security, not employers; night work and sectoral restrictions for women have been removed; and women can now choose, with the consent of their employers, flexible working arrangement adapted to personal and family circumstances.

In addition, the Labor Law now includes the concept of ‘wage discrimination’, imposes penalties on employers in case of discrimination, and obliges employers to establish a daycare facility when there are 15 or more children under five years of age in a company’s female and male workforce (previously the obligation existed only in the case of women employees).

In education, there practically is no gender gap in enrolments, while learning outcomes of girls exceed those for boys. In the labour market, women’s employment gains have been higher and the increase in unemployment lower than for men.

Conclusion

Differences in the availability of data may be responsible for some of the reported discrepancies among different assessments of Jordan’s progress on the SDGs. In addition, some assessments may use more or fewer indicators, and therefore be based on different information. For example, the national database has 162 indicators while the UN’s latest assessment is based on only around 100 indicators.

In addition, the reporting style is different. The global assessment uses four codes for the current status of SDGs and four directions of change. ESCWA uses three traffic lights (green, yellow, red) for progress or lack of it. National reports in Jordan at times are less detailed and presented in a narrative form instead of numbers. Finally, there are discrepancies concerning the indicators for which there is no information.

The SDGs are designed to be universal and serve this purpose well. They tend to be more accurate at the local level when there is ‘an elephant in the room’. SDG 8 on employment and growth in Jordan is a case in point.

In other words, global and regional assessments should be used in a qualified way when they are applied to different country realities that also have different development priorities. An overemphasis on quantitative indicators can neglect qualitative aspects of development, as it can be inferred from progress on SDG 5 on gender. These issues should be taken into account by donors regarding where to direct their advice and aid to Jordan.

On their side, countries should endeavour to conduct scientifically based surveys, use them in their policy-making and disseminate them in an accurate and timely manner. For example, in Jordan, there are no recent estimates of the poverty rate and the extent of inequality since 2017-18 when the latest survey on household expenditures and incomes (HEIS) was conducted, while there is no information on the poverty line since the early 2011. A follow up HEIS began in October 2021 and its results were expected by 2023. But this has been delayed due to technical reasons and the results of a new survey are now expected in 2026. In the meantime, a local newspaper has misreported that, according to the World Bank’s Atlas of the Sustainable Development Goals 2023, Jordan’s poverty rate has increased to 35%, something that cannot be found in the Bank’s database or publications. Such misinformation when fed to the citizens can potentially be more dangerous than the discrepancy between global and regional assessments of the SDGs.

Further reading

ESCWA (2023) ‘Counting the world’s poor: Back to Engel’s law’, Economic and Social Commission for West Asia.

Government of Jordan, Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation (2022) Third Voluntary National Review: Weaving Possibilities.

Government of Jordan, Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation (2023) Economic Modernization Vision 2023-33.

Government of Jordan, Ministry of Social Development (2019) National Social Protection Strategy (2019-2025), with UNICEF.

Jordan News (2024) ‘More than one-third of Jordanians live below poverty line’, 12 July.

Sachs, JD, et al (2021) Sustainable Development Report 2021, Cambridge University Press.

Sachs, JD, et al (2024) Sustainable Development Report 2024, Dublin University Press.

Tzannatos, Z. and I. Saif (2023) Assessing the Sustainability of Jordan’s Public Debt: The Importance of Reviving the Private Sector and Improving Social Outcomes. Cairo: ERF Working Paper Series No. 1649. August.

World Bank (2023) Atlas of Sustainable Development Goals 2023. World Bank (2024) Jordan: Poverty and Equity Brief.

The work has benefited from the comments of the Technical Experts Editorial Board (TEEB) of the Arab Development Portal (ADP) and from a financial grant provided by the AFESD and ADP partnership. The contents and recommendations do not necessarily reflect the views of the AFESD (on behalf of the Arab Coordination Group) nor the ERF.