In a nutshell

Development aid remains a critical source of financing for developing countries, particularly low-income countries, to meet their development goals.

Budget support, where resources flow from an external financing agency to the recipient government’s national treasury, is a key instrument to scale up support for both critical country-based reforms and to address global challenges, such as climate change and pandemics.

Getting the balance right between funding conditionality and country-level ownership is a key policy challenge for governments and multilateral development banks, as well as aid agencies around the world.

To meet their development goals, policy-makers in developing countries must prioritise a major funding push, together with policy reforms grounded in a sound macroeconomic framework. A new book – Retooling Development Aid in the 21st Century: The Importance of Budget Support – argues that reforms at the national level will need greater cross-border cooperation and a substantial expansion in financing from the global community, with multilateral development banks (MDBs) and other donors playing an increasingly important role.

Based on an extensive body of previous evidence, as well as the results of new research and evaluation, the book shows that budget support by MDBs can and should play a key role in helping developing countries to meet their economic, social and political challenges over the coming decade.

Development challenges

According to the United Nations, at the midpoint to 2030, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are in ‘deep trouble’. In fact, if the current concerning trend continues, nearly 580 million people will still be living in extreme poverty by 2030.

A series of global shocks have made the situation very challenging. The adverse effects of the global financial crisis of 2007-09, the Covid-19 pandemic and the continuing commodity crisis following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have increased the estimated annual investment gap in developing countries from $2.5 trillion to about $4 trillion. This includes the mounting costs of making the transition to clean energy in response to climate change.

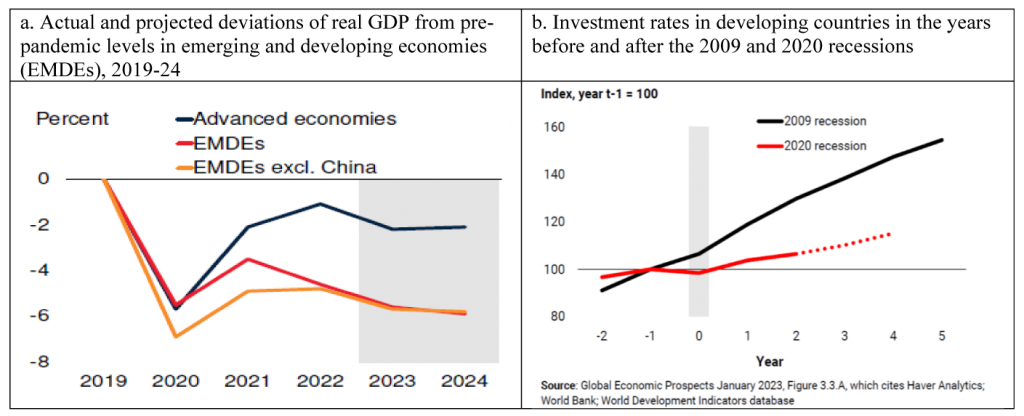

Slow post-recession recovery has exacerbated the resource deficit (Figure 1a), leading to a very tough set of conditions for policy-makers in these countries.

Figure 1. A deep recession followed by a slow recovery

Source: World Bank (2023) Global Economic Prospects, June.

At the same time, a structural growth slowdown is underway across the globe (World Bank). In the absence of either deep policy reforms or a substantial increase in development aid and private investment, global potential growth is expected to fall to a three-decade low over the remainder of the 2020s. Investment growth has been declining (see Figure 1b), and the labour force is ageing or growing more slowly in many countries. This only serves to make things harder.

The changing global aid architecture

Global aid architecture has changed substantially over the last two decades. Development aid has become more fragmented with the emergence of new donors (such as China), vertical funds and philanthropies.

But official development assistance and non-concessional lending by MDBs continue to play a critical role for developing countries. These official flows are often counter-cyclical – increasing following shocks such as financial crises, climate-related disasters and pandemics (see Figure 2a). By contrast, private flows, which dominate official flows to developing countries, have been pro-cyclical, declining when they are most needed (see Figure 2b).

Figure 2. Capital flows to developing economies remain anaemic

Sources: Authors for Figure 2a, based on financial statements, and OECD-DAC data on official lending; Figure 2b is based on KNOMAD-World Bank (2022) Migration and Development Brief 36.

Net official financial lending to developing countries, including budget support, is much smaller than private flows. But budget support, which on average constitutes about 20% of total official lending, punches well above its weight. It plays a key role in addressing critical economic reforms, supporting structural transformation in debt-stressed and other vulnerable countries, and facilitating the implementation of policy and institutional reforms that help to leverage private capital for development needs.

What is budget support?

Budget support refers to a method of financing a recipient country’s budget through the transfer of resources. These resources are moved from an external financing agency to the recipient government’s national treasury, with the funds then managed in accordance with the recipient country’s budgetary procedures. This differs from traditional project aid, which disburses resources against specific expenditures associated with a project (such as an educational programme or a large-scale infrastructure project).

Budget support is predicated on a policy dialogue between donors and recipients, and it is disbursed according to compliance with mutually agreed policy reforms. So, budget support is about policy dialogue, based on solid analysis, and it focuses on the development priorities of the recipient governments.

This idea is not new. Complementing traditional project lending, budget support emerged over a half century ago as an aid instrument to address macroeconomic imbalances conditional on key economic ‘reforms’ supported by the MDBs. It was widely used (and criticised) as an instrument for advancing the principles of the Washington consensus.

By the early 2000s, there was agreement that addressing the shortcomings of development assistance required greater country-level ownership, donor coordination, use of country systems, predictability and alignment with national poverty reduction strategies. Budget support, built on policy dialogue and conditioned on mutually agreed reforms, brought to the fore the importance of sound macroeconomic policies, good governance and institutional capacity (as well as recipient agency and control).

The Paris declaration and the Monterrey consensus incorporated a new vision for budget support, with measures aligned with recipient countries’ development strategies. Budget support was seen as the core instrument for macroeconomic policy dialogue and poverty reduction plans. Through this type of dialogue, coordinated donor engagement was supposed to bring the donor community and the government together around the recipient country’s own measures and development targets, especially in terms of eradicating extreme poverty.

What made budget support attractive were its promises to increase country-level ownership, build country capacity and strengthen country systems, rather than using parallel structures set up to satisfy donor requirements and coordination budgetary procedures. With increased ownership should come increased impact.

The evolving role of budget support

At the recent G20 meeting, the need for a substantial scaling-up of financing by MDBs was recognised by the heads of state. Such an increase is vital for helping developing countries to meet their development challenges.

MDBs are the most important financiers of budget support, accounting for about 85% of total funds, with policy conditionality becoming increasingly focused on medium-term institutional reforms (particularly public financial management reforms), and shifting towards fewer prior actions. But in several cases, early donor enthusiasm has given way to multiple agendas and fragmentation, with joint financing but disjointed ownership of conditionality. Getting the balance right between country-level agency and necessary conditionality remains a difficult task.

Meanwhile, new approaches to budget support have emerged over the last two decades. These include ‘deferred drawdown options’, which provide liquidity during times of crisis, and ‘policy-based guarantees’ to leverage private financing. Budget support has been deployed across countries at different income levels and different levels of institutional capacity, governance quality and political stability.

Recent budget support operations have focused on climate, social sectors and gender. Reforms to public sector governance continue to make up the largest share of policy actions. Budget support has been gradually extended to least developed countries, where poverty remains entrenched, institutions are weak and development prospects are uncertain.

As development challenges mount for countries around the world, it is as important as ever to ensure that aid programmes are effective. Budget support is a useful tool for development aid – and one that is likely to be increasingly relied on over the decade to come.

Further reading

Dieppe, Alistair (ed.) (2023) Global Productivity: Trends, Drivers Policies, World Bank.

Fardoust, Shahrokh, Stefan Koeberle, Moritz Piatti, Lode Smets and Mark Sundberg (2023) Retooling Development Aid for the 21st Century: The Importance of Budget Support, Oxford University Press.

Group of 20 (G20) (2023) ‘New Delhi Leaders’ Declaration’, September.

Irwin, Douglas, and Oliver Ward (2021) ‘What is the “Washington Consensus”?’, Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Landers, Clarence, and Rakan Aboneaaj (2022) ‘MDB Policy-Based Guarantees: Has Their Time Come?’, Center for Global Development.

World Bank (2015) ‘From Billions to Trillions: MDB Contributions to Financing Development’.

World Bank (2021a) ‘2021 Development Policy Financing Retrospective: Facing Crisis, Fostering Recovery’.

World Bank (2021b) ‘Deferred Draw-Down Option: Terms and Conditions’, Product Note, Treasury Department.

United Nations (2023) The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023: Special Edition.

https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2023/ United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) (2023) ‘SDG Investment Trends Monitor’, September.