In a nutshell

Many Arab countries have dualistic labour markets. This means they are essentially split into two core groups in terms of economic opportunities and outcomes.

Workers in public sector (insiders) jobs enjoy far more benefits and job security than their private sector counterparts (outsiders). Those with state jobs are protected from labour market reform by incumbent governments, who rely heavily on the middle class support to remain in power.

Unless governments are willing to challenge the status quo, economic growth will be hampered to the point of systemic collapse, plunging both insiders and outsiders into dire circumstances.

The Arab world is changing. Outside the wealthy and oil-rich Gulf states, the old social contract in the MENA region has been in decline for some time now. Fiscal crises and partial economic liberalisation since the 1980s have led to a gradual decline of the state-supported middle class (El-Haddad, 2020; Hinnebusch, 2020). States have withdrawn from guaranteeing public employment to graduates and the standard of living of incumbent public sector employees has stagnated or declined.

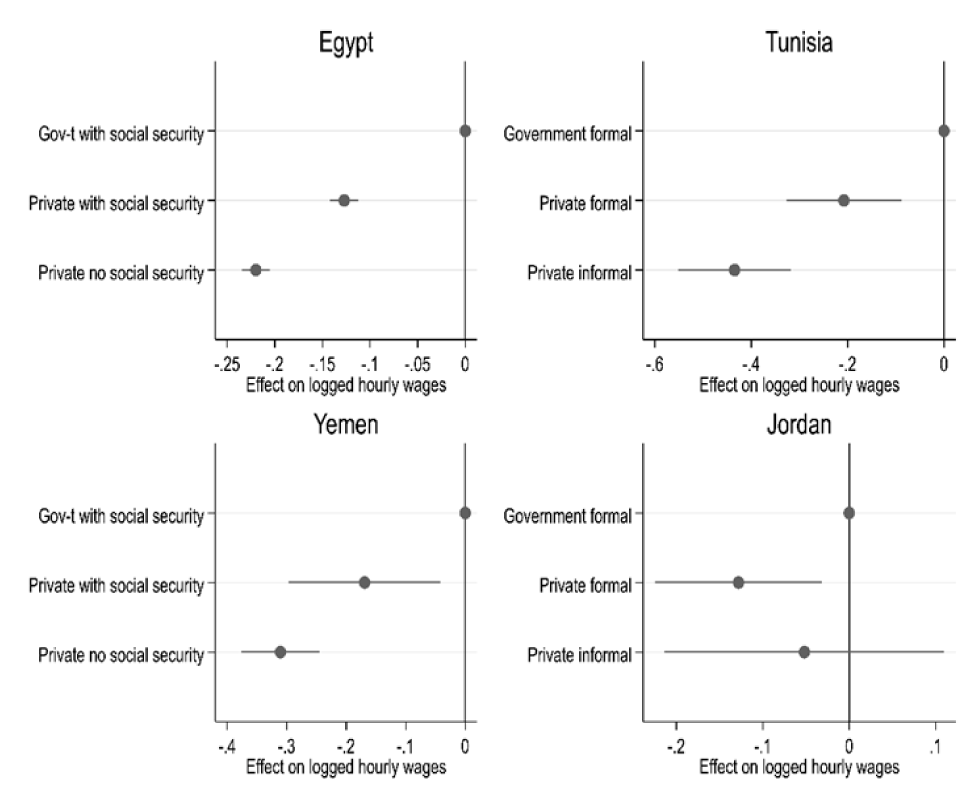

Yet, available data show that government employment remains the most attractive proposition for several key Arab labour markets (see Figure 1 below). While bureaucrats are not doing well, the growing numbers of labour market ‘outsiders’ in the private sector – especially those in informal employment – do substantially worse. Public sector jobs in the Arab region may no longer be what they used to, but the alternative is worse.

Figure 1: Effect of sector and formality on logged hourly wages

Source: Surveys obtained from Economic Research Forum (ERF). http://erf.org.eg/

data-portal/; various years from 2013 to 2018

NB: The coefficient plots are derived from regressions that take logged hourly wages as dependent variable and which control for age, age squared, urban versus rural residence, gender, occupation and, where available, region/governorate, marital status, and union membership. Survey weights were applied in all cases but Yemen, where the original data contain no weight variable.

This situation is nothing new. The persistent gap between publicly employed ‘insiders’ and private sector labour market ‘outsiders’ has been analysed extensively by economists who have pointed to the deep inefficiency of such segmentation in the Arab world (Assaad, 2014; Gatti et al., 2014). But in contrast to dual labour markets in Europe or Latin America, the phenomenon in the Arab context has barely been addressed from a political economy perspective. What keeps this dualism in place? What are its political consequences? And how is it linked to structures of exclusion in other parts of the economy?

These questions are addressed in a new book Locked Out of Development (Hertog, 2022). The core message of the text is that the Arab world’s economic development challenge is not simply one of ‘too much state’, as many pro-market reformers argue, or ‘state withdrawal’, as left-leaning critics argue, but is instead the state’s very uneven presence. By over-protecting some (insiders), while neglecting and marginalising others (outsiders), who are exposed to raw market forces with little protection and support, many Arab countries are unable to fulfil their growth potential. And it is not just labour markets but also private sectors which are deeply divided by insider-outsider cleavages – between politically connected firms on one hand and informal outsider firms on the other. These divides in different spheres then reinforce each other, further undermining economic progress in the region.

These patterns of exclusion are kept in place through the vested interests of insiders. Outsiders, by contrast, are much less well recognised as a political constituency. Bringing together evidence from across the Arab world’s core countries, the book shows that the insider-outsider divides across various Arab capitalist countries are deeper and more rigid than anywhere else in the Global South. This, I argue, contributes to the region’s disappointing economic outcomes.

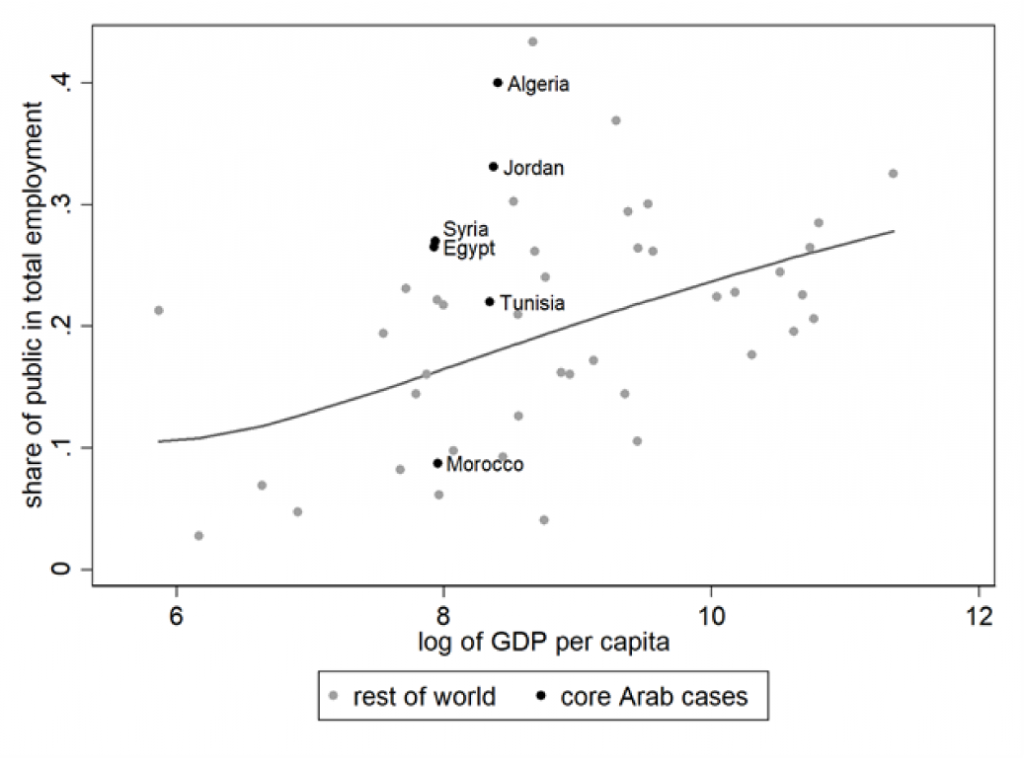

Divided labour markets

The dual nature of Arab labour markets has shaped politics for decades. Government employees are a core historical constituency of Arab regimes and their relative privileges have survived successive rounds of austerity surprisingly well. The shares of public sector workers in both the total workforce and among workers with a formal contract remain above the levels found in other developing regions (see Figure 2 below). And, unusually, across the Arab world most formal jobs are in government, not the private sector, where informal employment dominates.

Figure 2: Share of public in total employment

Sources: ILO, national sources

Insider jobs in government offer modest pay. In some cases, public sector workers have experienced substantial declines in real incomes. Yet, as shown above, hourly wages remain higher than in the private sector – even for the small number of private employees with formal contracts – which is unusual in global comparison. Job security and welfare benefits, especially pensions, remain much better than in the private sector.

But politically driven insider employment can impose large efficiency costs in the public sector (Tamirisia and Duenwald, 2018). Instances of ‘overemployment’ are staggering. For example, in 2021 Tunisair, which is primarily state-owned, had a fleet of 26 aircraft, of which only seven were operational. At this point in time the airline employed 7,600 individuals – more than 1,000 per functioning plane (AFP, 2021). This is clearly deeply inefficient.

Maintaining these insider constituencies is expensive (Tamirisia and Duenwald 2018). At the same time, fiscal constraints restrict new hiring, meaning young jobseekers have scant chances of getting a government job. Given weak job creation in the private sector, most young Arabs are either unemployed or stuck in precarious and badly paid informal work. Labour market data also show unusually low mobility between insider and outsider status (Hertog, 2022). Those who are informally employed or unemployed remain so for a very long time, while public sector insiders almost never leave their jobs. Crossing from one side of the labour market to the other is virtually impossible.

High spending on insider benefits leaves few resources to support outsiders on the private labour market side, who receive little or no social assistance. Spending on non-contributory social safety (i.e., benefits not tied to formal employment) is lower than in all other world regions, amounting to an average of only 1% of GDP across the Arab world (World Bank 2018). Non-contributory pensions, unemployment benefits and cash grant systems, while growing, remain underdeveloped, leaving the weakest behind.

The frustration of labour market outsiders has shaped Arab politics. In Tunisia in particular, this group has been prominent during social protests. Mohamed Bouazizi, the self-employed and unlicensed Tunisian street vendor, whose self-immolation triggered the Arab uprisings of 2010-11, was a quintessential outsider. Yet political feedback loops keep the current system in place: Regimes are afraid of touching insider privileges given their long-standing reliance on the state-employed middle class as core support basis.

To the extent that political mobilisation is possible, insiders also are better organised. This is most notable in Tunisia through the Tunisian General Labour Union (UGTT), which spends much of its political capital on defending insider interests and has a tense relationship with weaker organisations representing precarious workers and unemployed. Similarly, in Egypt, during its brief liberal window after the fall of Hosni Mubarak in 2011, newly emerging independent unions mostly represented state employees. Outsider groups stage occasional demonstrations, but they seldom demand systemic changes to labour markets or welfare systems. Instead, they tend to ask for government jobs – essentially demanding to be made insiders.

Divided private sectors

Dualism in the labour market is reinforced by dualism in the wider private sector across the Arab region. Politically protected insider firms contribute little to job creation (Diwan et al., 2020), and nepotism in private labour markets undermines mobility for outsiders (Gatti et al., 2013). At the same time, smaller outsider firms can typically only offer precarious and badly paid informal jobs. All this reinforces the reliance of the shrinking Arab middle class on government for secure employment. The system gives few incentives for skills formation: Insider firms are so secure that they do not need to invest in skills and training, while outsider firms do not have the resources to do so. Workers in turn face limited payoffs to skills acquisition given the limited mobility of labour markets. The system is in gridlock.

A new social contract?

The ‘Nasserist model’ of maintaining a broad middle class through state employment has become unaffordable and its shrinkage has led to deep social exclusion. But simply downsizing the state further is not a viable solution, given how few good jobs the private sector currently provides. What the region instead needs is an ‘egalitarian liberalisation’, under which insiders give up some of their privileges while the state steps up its support for outsiders. It should do so through more systematic investments into universal social security and safety mechanisms, entrepreneurship and skills.

Public sectors could also be downsized. This could take place through voluntary golden handshake policies, early pensions packages and assistance programmes for finding private jobs – all coupled with state wage support for lower earners in the private sector to reduce wage inequality, combat poverty more effectively and make private employment a socially viable proposition. The alternative to this is the economic collapse of the current system, which will impoverish both insiders and outsiders – an outcome which Egypt, long a bellwether of economic change in the region, has already veered dangerously close to.

Further readings

AFP. 2021. “Tunisia’s Debt-Laden Public Companies Edge toward Ruin.” March 7, 2021.

Assaad, Ragui 2014b. “Making Sense of Arab Labor Markets: The Enduring Legacy of Dualism.” IZA Journal of Labor & Development 3(1):6.

Diwan, Ishac, Philip Keefer, and Marc Schiffbauer. 2020. “Pyramid Capitalism: Cronyism, Regulation, and Firm Productivity in Egypt.” The Review of International Organizations 15(1): 211–246

Gatti, Roberta, Diego Angel-Urdinola, Joana Silva, and Andras Bodor. 2014. Striving for Better Jobs: The Challenge of Informality in the Middle East and North Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank

Gatti, Roberta, Matteo Morgandi, and Rebekka Grun. 2013. Jobs for Shared Prosperity: Time for Action in the Middle East and North Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank

El-Haddad, Amirah. 2020. “Redefining the Social Contract in the Wake of the Arab Spring: The Experiences of Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia.” World Development 127: 104774

Hertog, Steffen. 2022. Locked Out of Development: Insiders and Outsiders in Arab Capitalism. Cambridge Elements: Cambridge University Press

Hinnebusch, Ray. 2020. “The rise and decline of the populist social contract in the Arab world” World Development 129: 104661

Tamirisa, Natalia, and Christoph Duenwald. 2018. Public Wage Bills in the Middle East and Central Asia. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

World Bank. 2018. The State of Social Safety Nets 2018. Washington, DC: World Bank.