In a nutshell

The devaluation of the Egyptian currency and the Russia-Ukraine conflict have worsened the economic situation in Egypt, leading to a surge in inflation rates on food items.

Children living in vulnerable households are at high risk of food insecurity and malnutrition; Egyptian officials urgently need to ensure that benefits reach poor households, especially those with children.

The country needs to make a priority of developing a child-focused national, multisectoral action plan to prevent the rise in malnutrition rates and reduce undernutrition.

The Russia-Ukraine crisis is hitting the global economy at a time when the world is struggling to recover from the economic repercussions of the Covid-19 pandemic. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 added fuel to the fire for a global economy already suffering from the pandemic’s slowdown of the global flow of commodities and the disruption of supply chains (Santacreu and LaBelle, 2022).

Wars leave their marks on the global economy in the form of rising inflation rates, service restrictions, increasing debts and more obstacles in people’s daily economic lives. Yet the negative impacts of the Russia-Ukraine crisis have been more pronounced, particularly for low- and middle-income countries. This article highlights the dire consequences of the crisis for food security in Egypt, which is likely to result in higher risks of malnutrition in children.

The Russia-Ukraine crisis and the Egyptian economy

Egypt has historically had strong economic ties and deep-seated trading relationships with both Russia and Ukraine. Due to its vulnerable economic position – with low foreign exchange reserves, high interest payments, quickly rising inflation rates and an unstable tourism sector – Egypt’s economic struggles are expected to worsen with the continuation of the crisis.

The economic implications of the crisis have impinged on already high inflation rates, the imports of wheat and other necessary products, and the dwindling influx of tourists. The threat of food insecurity is particularly palpable since Egypt relies heavily on food imports. During the five years prior to the crisis, Egypt sourced an average of approximately 85% of its wheat imports from Ukraine and Russia (UN Comtrade, in: Abay et al, 2022).

This wheat is an essential and strategic crop because it is a main component of traditional Egyptian baladi bread, which households depend on heavily in their daily food consumption. In addition, the global spikes in food prices, coupled with a frequently rising domestic inflation, have raised concerns about food security among the country’s most vulnerable households.

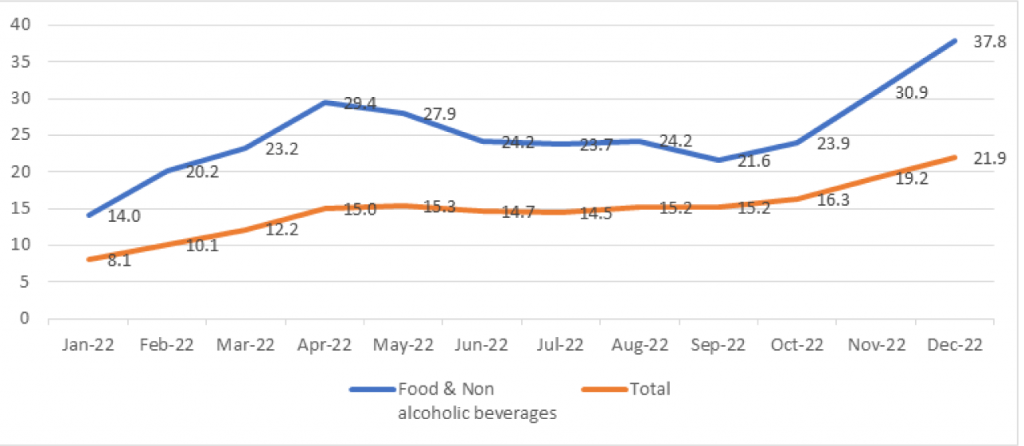

Shortly after the crisis began, in March 2022, the inflation rate in Egypt increased to 12.1% compared with March 2021. The rate continued to escalate, reaching a peak of 15.3% in May 2022. After the devaluation of the Egyptian pound in late October 2022, the rate again rose, reaching 21.9% by December 2022.

Figure 1: Total inflation rates and food inflation rates in 2022 compared to the corresponding month in 2021

Data source: CAPMAS, 2022b, 2022c

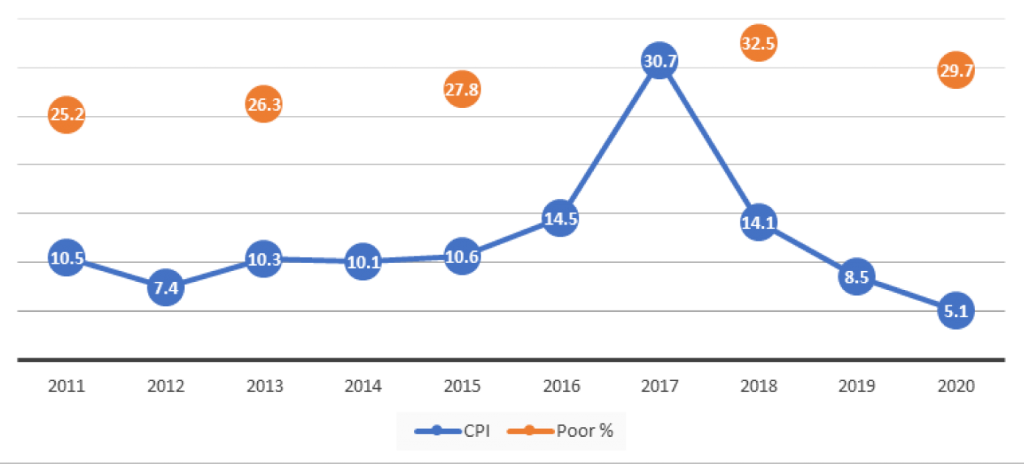

Figure 2: Annual inflation and poverty rates, from 2011 to 2020

Data source: CAPMAS, 2022b

As Figure 2 shows, the number of poor increases when inflation rates rise, especially when net incomes do not increase, or they increase at lower rates. The rise in poverty rates usually implies a decrease in spending on, and consumption of, essential food and non-food items, which is indicative of food insecurity.

In April 2022, the World Food Program (WFP) estimated that the Russia-Ukraine crisis would increase the number of those suffering from acute hunger by about 47 million people to 323 million people. The estimates include six million people in the Middle East and North Africa (WFP, 2022b). Additionally, around 60 million children worldwide will be acutely malnourished in 2022, rising from 47 million in 2019 (WFP, 2022a).

Implications for the food insecurity of children in Egypt

During previous economic crises, vulnerable families in Egypt frequently resorted to reducing food consumption to cope with financial difficulties (CAPMAS, 2020a, 2020b, 2022a). The inflation of food prices, and the resulting reductions in food consumption are difficult for children of poor households, leading to malnutrition and affecting physical and cognitive development. Based on previous data, the rising inflation rates caused by the crisis are likely to lead to changes in food consumption patterns.

Escalations in inflation rates from January 2022 to December 2022 mostly affected the prices of bread and cereal, which increased by 58.3%. The prices of milk, cheese and eggs also increased by 48.9% in December 2022. These ingredients are crucial for children’s growth.

In a CAPMAS phone survey (2022a), 74% of the households interviewed had reduced their food consumption due to the spikes in food prices that resulted from the crisis. Most households, 93%, reduced their protein consumption, 69% reduced egg consumption, while 57% reduced vegetable consumption and 69% reduced fruit consumption.

According to HIECS 2019, more than 92% of poor households have children. Since poverty is more prevalent among households with children, these reductions in food consumption are likely to hinder children’s nutrition.

Government mitigation and policy recommendations

The children of vulnerable households in Egypt face greater risks of food insecurity and malnutrition as the Russia-Ukraine crisis continues. There are several short- and medium-term interventions that the Egyptian government can make to address these detrimental risks.

The government currently has several programmes that protect vulnerable households with children. These include the Takaful and Karama Program (TKP), food subsidies, and the National School Feeding Program (NSFP). Households that include at least one TKP beneficiary are less likely to fall back from vulnerable status to poverty status (UNICEF, 2020).

Food subsidies also contribute to food poverty reduction, as extremely poor households are highly dependent on food cards (around 92% in HIECS 2019/20). Finally, the NSFP, which aims to improve children’s nutrition and promote school enrolment, also supports poor families by providing children with nutritious school lunches.

In the short term, officials should ensure that TKP benefits reach extremely poor households, especially those with children. They should expand school meal programmes to ensure that more vulnerable children receive the nutrition they need for healthy growth.

Officials can also develop a child-focused, national, multisectoral action plan to prevent a rise in malnutrition rates. It is important to diversify sources of wheat imports while considering wheat alternatives for affordable staple foods. In addition, expert officials can implement social behaviour change interventions to promote a diversified diet and the consumption of locally available nutritious foods to replace wheat.

In the medium term, social protection programmes such as the TKP, school meals and the ration card system need to be evaluated and developed to have broader reach. Additionally, each stage of the bread supply chain needs to be effectively managed to reduce food waste. Finally, Egypt should invest in more food fortification programmes.

Further reading

Abay K, F Abdelradi, C Breisinger, X Diao, P Dorosh, K Pauw, J Randriamamonjy, M Raouf and J Thurlow (2022) ‘Egypt: Impacts of the Ukraine and Global Crises on Poverty and Food Security’, International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

CAPMAS, Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (2019) ‘Households Income, Expenditure and Consumption Survey 2017/2018’.

CAPMAS (2020a) ‘The Impact of COVID-19 on Egyptian Households till May 2020’.

CAPMAS (2020b) ‘The Impact Of COVID-19 On Egyptian Households till September 2020’.

CAPMAS (2022a) ‘The Impact of Russia-Ukraine Crisis on Egyptian Households 2022’.

CAPMAS (2022b) ‘Monthly Bulletin of Consumer Price Index (CPI) Aug 2022’.

CAPMAS (2022c) ‘Monthly Bulletin of Foreign Trade Data May 2022’.

Santacreu AM, and J LaBelle (2022) ‘Global Supply Chain Disruptions and Inflation During the COVID-19 Pandemic’, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 104(2): 78-91.

UNICEF, United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (2020) ‘In and out of Poverty: An Analysis of Egyptian Poverty and Vulnerability Dynamics Between 2015 and 2017/2018’.

WFP (2022a) ‘War in Ukraine Drives Global Food Crisis’.

WFP (2022b) ‘Projected Increase in Acute Food Insecurity Due to War in Ukraine’.