In a nutshell

During the Covid-19 crisis, one-third of Tunisians were mildly depressed, one-fifth of them suffered from moderate depression and almost 41 in 1,000 people experienced severe depression.

People’s age and the size of their household can influence their mental health; and having a higher level of education can strengthen individuals’ resilience against damaging effects on mental health of experiences like the Covid-19 crisis.

There is clear evidence that instability of household income caused by job loss has contributed significantly to the worsening of people’s mental health.

Following the World Health Organization’s (WHO) recommendations and to slow the rapid spread of Covid-19 across and within countries, many governments responded with strict measures, including lockdown with border closures, restrictions on travel, self-isolation, social distancing and school and workplace closures (Schomaker et al, 2021; Nasri et al, 2021).

These measures resulted in a significant rise in unemployment in many countries (Blustein et al, 2020). According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), losses of working hours in 2020 were approximately four times greater than those during the global financial crisis of 2009 (ILO, 2021).

Job loss means not only the loss of income and financial benefits for many people but also a loss of identity. Hence, it can also be a major reason why they may experience symptoms of depression more than those maintaining their status in the labour market. It is increasingly being recognised that in addition to economic costs, the health costs of Covid-19 are not limited to physical health but include the effects of the pandemic and restrictions on people’s psychological wellbeing (Petersen et al, 2021).

Tunisia, like most countries, used various measures to prevent the spread of Covid-19 across the country as once the disease circulates, authorities are forced to adjust their strategy to reduce the burden on the health system. On 22 March 2020, total population containment was imposed on Tunisia for two weeks and it was extended twice (Nasri et al, 2021).

The lockdown made job search more difficult or impossible in certain cases, and many workers lost their jobs (Krafft et al, 2021). Being worried about the indefinite duration of the disease was associated with severe symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Indeed, fear, worry and stress are normal responses to perceived or real threats and also when dealing with uncertainty or the unknown. It is therefore understandable that people have experienced fear and depression in the context of the pandemic. Using Tunisian micro-data from the ERF Covid-19 MENA Monitor Household Survey (OAMDI, 2021) fielded primarily in November 2020, we have analysed how the mental health in Tunisia was affected during crisis.

Mental health indicators and symptoms of depression

People’s mental health was measured using the WHO-5, introduced in the survey questionnaire under the ‘Mental Health’ module (OAMDI, 2021). The WHO-5 is a short questionnaire consisting of five simple items that tap into the subjective wellbeing of respondents:

- ‘I have felt cheerful and in good spirits.’

- ‘I have felt calm and relaxed.’

- ‘I have felt active and vigorous.’

- ‘I woke up feeling fresh and rested.’

- ‘My daily life has been filled with things that interest me.’

Respondents are asked to rate how well each of the five statements applies to them over the past 14 days. Each of the five items is scored from 5 (all of the time) to 0 (none of the time). The raw score ranges from 0 to 25, where 0 represents the worst possible mental health and 25 represents the best possible mental health. This raw score is generally compared to the mean score of the population.

From the WHO-5 items, we identify the following three syndromes: depressed mood (B1), reduced energy (B2) and loss of interest (B3). If the individual scored 0-2 on item 1, they were considered in a depressed mood (B1); they were categorised as having decreased energy (B2) if they scored 0-2 on either item 3 or 4 and as having loss of interest (B3) if they scored 0-2 on item 5.

These three syndromes allow us to classify people into three depression types (mild, moderate and severe). We assume that individuals suffered from mild depression if they manifest syndrome B1 or syndromes B2 and B3. We consider those with the syndromes (B1 and B2) or (B1 and B3) as people with moderate depression. Conversely, depression is considered severe if people had all three syndromes (B1, B2 and B3).

Individual characteristics influencing mental health during Covid-19 crisis

Of the people in the sample, 37.75% had overall mental health scores lower than the mean population score (16,921). This rate varied according to the socio-demographic characteristics of the individuals: 41.7% of people living in rural areas had scores lower than the average score of the total population, while this rate was 36.06% for those in urban areas.

There was a slight difference between the rate for men (38.52%) and that for women (36.65%); but this rate varied considerably depending on the age group. A total of 31.65% of people aged 18-29 had scores lower than the mean score of the population, while this rate exceeded 44% for people aged 50-64.

Similarly, the highest rate among individuals living in large families was around 40%. This rate dropped to 36.64% for people living in households of three to four people and to 33.33% for households of one or two people.

The rate decreased each time the level of education increased: over 40% for people with basic and less than basic levels, and 27.7% for those with higher education levels. This rate was also 39.15% for married people and 32.85% for unmarried people (never married, divorced or widowed), while those living with children under the age of six at home had the highest rates (39.18%).

We analyse the proportion of people suffering from depressed mood, decreased energy and loss of interest. Our results show that 29.2% of individuals had a depressed mood after the first wave of Covid-19. The highest rates were among those aged over 50 (34.9%), those with a less than basic educational level (37.5%), those living in families of at least five people (32.05%), married people (30.89%) and women (29.5%). The second symptom was decreased energy, the highest rates of which were for men (34.86%) and people aged over 40 (37%).

Furthermore, 41.66% of individuals with less than a basic educational level suffered from this second symptom. For people living with children under the age of six, this rate was 38.5%. As for the third symptom, only 10.5% of individuals experienced a loss of interest. Unlike the other two symptoms, loss of interest was more common in those aged 30-39, those living in households of one or two people, and unmarried people, with rates at 11.28%, 11.25% and 13.6%, respectively.

Based on these three symptoms, we classify people as having three types of depression: mild, moderate and severe. Of those in the sample, 31.6% suffered from mild depression and the highest rates were among men (32.14%), those aged 50-64 (37.92%), married people (33.09%) and those who did not have a basic educational level (40.83%). The mild depression type included those who had either depressed mood symptoms or both decreased energy and loss of interest at the same time.

Moderate depression was identified in those with two symptoms at the same time, namely either depressed mood and decreased energy or depressed mood and loss of interest: 20.2% of people had moderate depression, with those over 50 (24.90%) and women being the most affected (20.87%) compared with men (19.72%).

The rate of young people aged 18-29 affected by moderate depression was 14.78% and that for those who had completed a higher educational level 12.74%. The lowest rates were for unmarried people (16.75%) and those living in a family of no more than two people (15.83%).

People were considered to have severe depression if they experienced a depressed mood, decreased energy and loss of interest at the same time. We find that 4.1% of people had severe depression. Similar to the other two types of depression, the highest rates were among those aged 50-64 (5.47%), those living in large families (4.6%) and those with a less than basic educational level (6.04%). This rate decreased when educational level increased.

Symptoms of depression and labour market status

We follow the same identification strategy as Krafft et al (2021) to identify individuals who lost jobs following the social distancing measures applied in Tunisia during the first wave. Workers who lost their jobs were working in the private sector, in the public sector or as self-employed in February 2020 and became unemployed (self-reported) by October 2020.

People were grouped into two sub-populations: the first one, denoted G_1, included those who had lost their jobs; the second group, denoted G_2, included those whose status in the labour market had remained unchanged. Workers who switched positions or activity sectors were excluded.

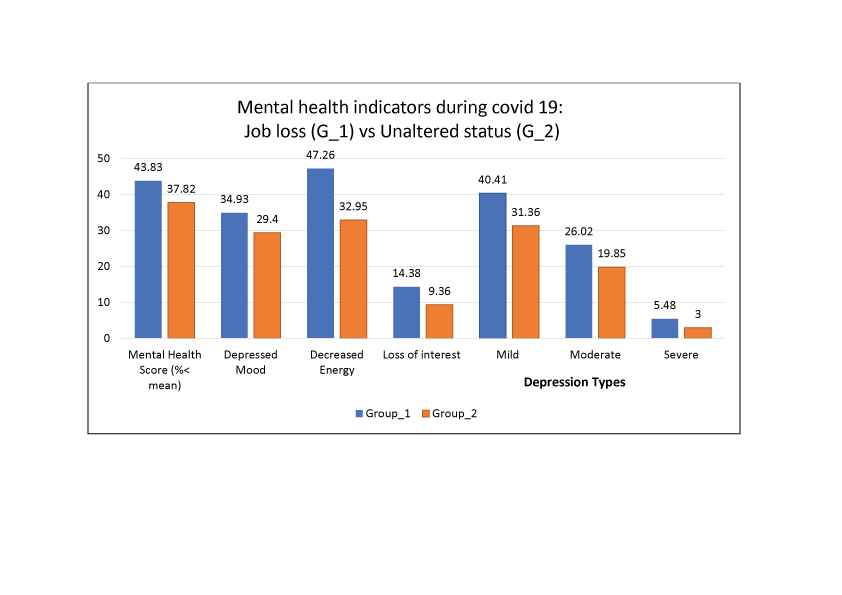

Figure 1: Comparison of mental health indicators between G_1 and G_2

Source: Author’s calculation

As Figure 1 shows, all the mental health indicators of individuals who had maintained their employment status were significantly better than for those who had lost their jobs. The percentage of individuals with mental health scores lower than the mean score of the total population was 37.83% in G-2, while this rate reached 43.83% in G_1. In addition, the three symptoms of depression were more prevalent in those in G_1.

Our results show that 34.93% of G_1 had a depressed mood, while this rate was 29.4% for G_2. In addition, 47.26% of G_1 felt a decrease in energy, while this rate was 32.95% in G_2. Regarding the loss of interest, this symptom was present in 14.39% of G_1 and did not exceed 10% in G_2.

On the other hand, more than 40% of individuals who had lost their jobs had mild depression; but this rate was 31.36% for G_2. More than a quarter of G_1 had moderate depression and about 5.5% had severe depression. But these two types of depression (moderate and severe) affected 19.85% and 3% of those in G_2, respectively.

Conclusion and policy recommendations

Our results show that three in ten people were in a depressed mood between October and November 2020. Decreased energy symptoms were present in four in ten people, particularly those aged 50-64 and those with less than basic education, regardless of their age.

Compared with the other symptoms, the loss of interest symptom was not dominant during the crisis. In addition, almost one-third of the sample were mildly depressed, one-fifth of them suffered from moderate depression and almost 41 in one thousand people experienced severe depression.

Our findings also show that age and size of the household can influence mental health, and having a higher level of education can strengthen people’s resilience against mental effects during the crisis. But we have not been able to observe that mental health indicators constantly differ according to sex or marital status. In addition, there is clear evidence that instability of household income caused by job loss has contributed significantly to the worsening of people’s mental health.

From this analysis, several policies are recommended. Other than financial aid to encourage firms to keep their workers, psychological support policies intended for vulnerable groups such as elderly people and those with a low level of education should have been implemented. These can strengthen the capacity to resist health shocks like Covid-19.

There is an urgent need to establish a job loss insurance system managed by an independent fund, bringing together employees made redundant for economic or technical reasons as well as graduates who have completed their higher education and have been unemployed for some time by supporting and accompanying them in the implementation of projects.

Even though such unemployment benefits may seem costly, their positive effects on social and economic conditions in the long run are highly important. They keep the unemployed linked to the labour market, avoiding more costly economic, social and mental health consequences in the future. In addition, informal workers are encouraged to participate in the social security system to receive benefits in the event of job loss or old age.

Further reading

Blustein, DL, R Duffy, JA Ferreira, V Cohen-Scali, RG Cinamon and BA Allan (2020) Unemployment in the time of Covid-19: A research agenda, Elsevier.

ILO, International Labour Organization (2021) ILO Monitor: Covid-19 and the world of work, 7th edition.

Krafft, C, R Assaad and MA Marouani (2021) ‘The impact of Covid-19 on Middle Eastern and North African labor markets: Vulnerable workers, small entrepreneurs and farmers bear the brunt of the pandemic in Morocco and Tunisia’, ERF Policy Brief No. 55.

Nasri, K, H Boubaker and N Dhaouadi (2021) ‘Dynamic governance of the first wave of Covid-19 in Tunisia: An interoperability analysis’, ERF 27th annual conference: SDGs and external shocks in the MENA region from resilience to change in the wake of Covid-19.

OAMDI (2021) Covid-19 MENA Monitor Household Survey (CMMHH), ERF.

Petersen, MW, TM Dantoft, JS Jensen, HF Pedersen, L Frostholm, ME Benros, TBW Carstensen, E Ørnbøl and P Fink (2021) ‘The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on mental and physical health in Denmark – A longitudinal population-based study before and during the first wave’, BMC Public Health.

Schomaker, RM, M Hack and A-K Mandry (2021) ‘The EU’s reaction in the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic between centralisation and decentralisation, formality and informality’, Journal of European Public Policy 28(8), 1278-98.