In a nutshell

The role of the unofficial economy in mitigating political unrest during an economic downturn suggests the need to reconsider calls for its elimination: informal activities serve as an implicitly or explicitly integral part of social risk management strategies.

Attempts at the reduction or abolition of the shadow economy should be complemented by an increase in or establishment of other risk management pillars, such as social security payments and unemployment insurance.

Industrial diversification strategies can serve as an important complement to strategies aimed at reducing the role of the shadow economy; accompanying deregulation and structural adjustment strategies must be designed carefully.

Resource-rich countries are subject to severe commodity price swings that can significantly affect their macroeconomic fundamentals, including political unrest (see Bazzi and Blattman, 2014 for a survey).

Widespread political instabilities are associated with a higher risk of investment and capital flight, displacement of population, and destruction of infrastructure and social capital. These may have significant negative effects on economic growth. For example, in the case of the Arab Spring protests in Tunisia, Matta et al (2019) estimate the income lost to range between 5.5% and 6.4% of GDP over the period 2011-13.

But little is known about whether fluctuations in international oil prices can induce political instability in oil-dependent countries with sizable shadow economies. In the context of oil-producing countries, investigating such a role is particularly appealing not only because of the vulnerability of those economies to external shocks, but also because of the considerable share of informal economies in their official GDP.

According to Medina and Schneider (2018), the average share of the shadow economy to GDP in oil-producing countries ranges from 11% to 62%, with an average of approximately 31%. This points to the significant role of the informal sector in those economies.

In our new study (Ishak and Farzanegan, 2021), we focus on protest events, as measured by the number of anti-government demonstrations, general strikes and riots (drawing on Banks and Wilson, 2018). Our indicator for the shadow economy comes from Medina and Schneider (2018) and covers the production of legal goods and services that goes unregistered for variety of reasons such as tax and regulatory evasions.

How are oil rents, protests and the shadow economy interconnected?

A sudden decline in oil rents may increase pressure on the state to cut subsidies, reduce the size of the public sector and increase the tax burden. For example, the oil-rich countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) have started to introduce value added taxes and other fees as a result of negative oil shocks (Edwards, 2020).

These developments, especially in oil-rich economies, may increase the risk of social unrest. A reduction in subsidies and cash payments can also have adverse effects on inequality and poverty indicators. It can negatively affect the size of the middle class and shift them to lower income deciles, thus reducing the opportunity cost of joining anti-state protests.

But shadow economies can act as a countercyclical device to buffer social unrest by providing an alternative source of income for disgruntled citizens during an economic downturn (for example, Eilat and Zinnes, 2002).

Furthermore, shadow economies may offer leeway from the distortionary activities of the state in the formal economy, such as administrative corruption, leading to enhanced economic activities in the formal sector (for example, Choi and Thum, 2005). In this setting, the existence of a shadow economy may increase the opportunity cost of protesting during periods of sluggish growth following a decline of oil rents in oil-dependent economies.

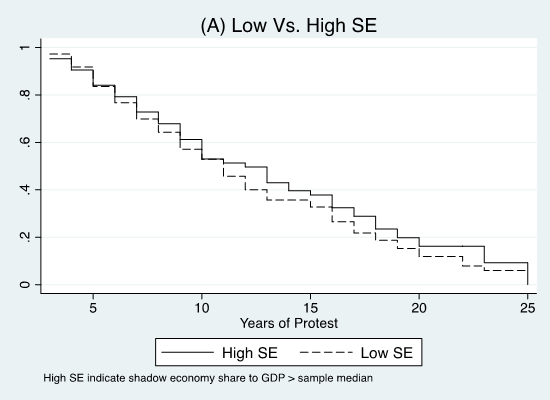

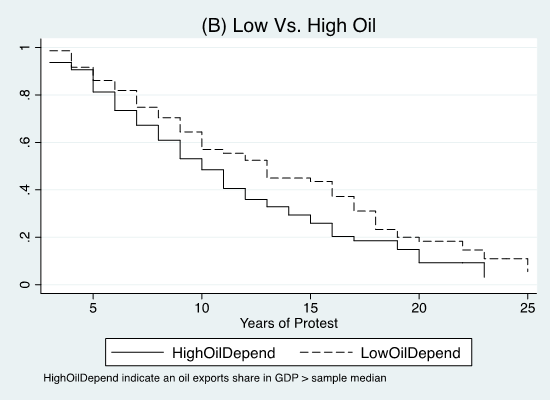

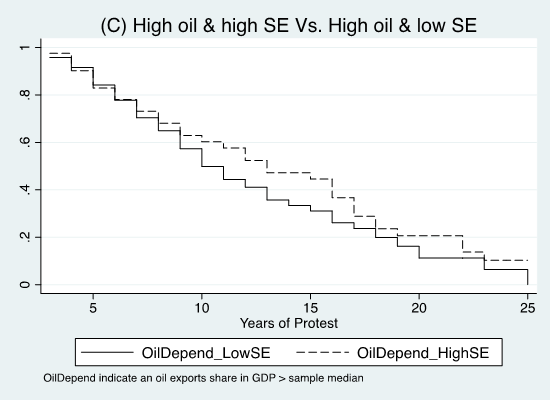

To get an initial snapshot of this relationship, Figure 1 shows the life table survival estimates for country groups classified based on the degree of their dependency on oil revenues and the size of their shadow economies.

The graph of the protest survival function in Figure 1(A) indicates that the average survival rate for experiencing protests is slightly higher for countries where the share of the shadow economy to GDP is greater than the sample median (‘high shadow economy countries’) compared with the rest (‘low shadow economy countries’).

Put differently, high shadow economy countries may have a slightly lower likelihood of witnessing protests than low shadow economy countries. But the log-rank test for equality of survivor functions fails to reject the null hypothesis that both groups are equal. This means that there is no statistically significant difference for the likelihood of witnessing protests between small and large shadow economy countries.

Figure 1(B) plots the protest survival function for countries whose share of oil exports to GDP is greater than the sample median (‘high oil-dependent countries’) against countries with lower dependency on oil (‘low oil-dependent countries’).

It shows that the average survival rate for experiencing protests is lower for high oil-dependent countries and that there is a higher likelihood of witnessing protests in high oil-dependent countries compared with low oil-dependent countries. The log-rank test for equality of survivor functions rejects the null hypothesis that both groups are equal.

Finally, Figure 1(C) plots the protest survival function for high oil-dependent countries with large shadow economies against high oil-dependent countries with small shadow economies.

It suggests that the average survival rate for experiencing protest is higher for high oil-dependent countries with large shadow economies relative to those with small shadow economies. The log-rank test for equality of survivor functions rejects the null hypothesis that both groups are equal.

Figure 1: Protest survival functions

Key results

Using panel data on 144 countries, covering the period from 1991 to 2015, we (Ishak and Farzanegan, 2021) first find that negative oil price shocks increase the incidence of protests.

We also show that the shadow economy significantly reduces the incidence of protests and that negative oil price shocks cease to have any significant impact on protests in countries with sizable shadow economies (representing more than 35% of GDP).

This can be attributed to the safety net provided by the shadow economy as an alternative market to avoid the distortionary interventions of the government in the formal economy.

Policy conclusions

This finding has several implications. First, such a mitigating role should allow for reconsiderations of permanent calls to eliminate the unofficial economy, by depicting it as a source of evil, a stance that simply conflates causes with symptoms. Governments must recognise that the existence of a shadow economy serves as an implicitly or explicitly integral part of social risk management strategies.

Second, even with the justified objective of eliminating inefficiencies in allocating goods and factors in the economy, deregulation and structural adjustment strategies must be designed carefully. Specifically, strategies must be implemented in such a way that a reduction or abolition of the shadow economy will be complemented by an increase in or establishment of other risk management pillars (social security payments, unemployment insurance, etc.).

Third, diversification of production will reduce state dependency on oil revenues and therefore, economic vulnerability to shocks. Thus, industrial diversification strategies can serve as an important complement to strategies aimed at reducing the role of the shadow economy. Ultimately, the existence of the shadow economy is a response to unsound economic policies and inefficient economic structures that fail to shield the economy against shocks, aspects that should be addressed in advance.

Further reading

Banks, AS, and KA Wilson (2018) ‘Cross-national time-series data archive’, Databanks International.

Bazzi, S, and C Blattman (2014) ‘Economic shocks and conflict: evidence from commodity prices’, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 6(4): 1-38.

Choi, JP, and M Thum (2005) ‘Corruption and the shadow economy’, International Economic Review 46: 817-36.

Eilat, Y, and C Zinnes (2002) ‘The shadow economy in transition countries: Friend or foe? A policy perspective’, World Development 30(7): 1233-54.

Ishak, PW, and MR Farzanegan (2021) ‘Oil price shocks, protest and the shadow economy: is there a mitigation effect?’, Economics & Politics, forthcoming.

Matta, S, S Appleton and M Bleaney (2019) ‘The impact of the Arab spring on the Tunisian economy’, World Bank Economic Review 33(1): 231-58.

Medina, L, and F Schneider (2018) ‘Shadow economies around the world: what did we learn over the last 20 years?’, IMF Working Paper No. 18/17