In a nutshell

Cultural populism involves favouring a particular race, nationality, religion, sect, or class as the ‘real people’, at the expense of others.

Rapid and drastic changes in a country’s demographic and socio-economic structure often lead to cultural populism.

When different types of populism occur simultaneously, they interact and feed each other.

Changes in a country’s demographic make-up are one of the factors that trigger cultural populism. When the proportion of foreign-born people in the population rises, especially when the newcomers differ from the natives in terms of race, ethnicity, religion, sect and language, and are concentrated in particular regions, we encounter a cultural populism that pits the natives against the migrants.

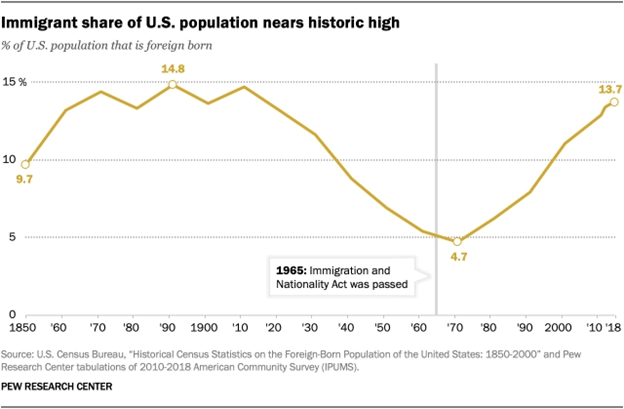

For example, recent rise in anti-migrant sentiments in the United States can be attributed to the rise in the proportion of foreign-born people in the population from 5% in 1965, when the country quota system was ended, to 14% now (Figure 1). When the US-born children of migrants are included, the latter proportion rises to 28%.

Figure 1

In addition, of the immigrants who arrived after 1965, half were from Latin America and a quarter from Asia. This, and the drop in the birth rate of the natives of European ancestry, caused the share of non-Hispanic whites in the population to drop to 61% from 84% in 1965. During the same period, the proportion of Hispanics increased from 3% to 18%, and of Asians from 1% to 6%.

A similar situation occurred in the United States towards the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, and elicited similar responses. The share of foreign-born people in the population reached 15% in 1890. Also, as a result of new migration from countries such as Ireland, Poland, Italy, Austria and Hungary, the proportion of Catholics in the population rose to 17% in 1906 from 5% in 1850. This created the anti-Catholic ‘Know Nothings’ movement, akin to the anti-Muslim and anti-Hispanic movements we observe today.

This led to the country-quota system, which severely restricted migration from southern and eastern Europe. Although it was relatively small, migration from Asian countries stirred anti-migrant sentiments as well because it was concentrated on the west coast. As a consequence, all migration from Asia (except Russia), including the Middle East, got banned. This remained in effect until 1952 and the quota system until 1965.

Now, in many European countries, the proportion of foreign-born people is even higher than in the United States and is rising much faster. As a result of rapid migration from the Middle East and North Africa, Muslims now account for 5% of the European population. No doubt, the sudden jump in the number of racist and anti-migrant parties in Europe is related to that. Syrian refugees in Turkey, who, in a very short time, became 4-5% of the country’s population, generated milder but similar reactions.

The presence of ethnic and religious minorities in a society presents populists with opportunities similar to those from high migrant numbers.

Rural versus urban

In most countries, internal migration has sorted people into urban, suburban, ex-urban and rural segments with different lifestyles and wealth. This has provided cleavages for populists to exploit. Indeed, the US Populist movement, which coined the term, emerged from the rural-urban divide.

Results of the last two US presidential elections can be taken as one manifestation of this. In 2016, the 472 mostly urban counties in which Hilary Clinton came first accounted for 64% of US GDP, whereas the 2,584 mostly rural counties in which Donald Trump came first accounted for only 36% of it. In 2020, 509 counties won by Joe Biden accounted for 71% of US GDP, whereas 2547 counties won by Donald Trump accounted for only 29% of it.

Political manifestations of the rural-urban divide can also be observed in the results of the UK Brexit referendum and the 2017 French presidential election.

In developing countries such as Turkey, which went through radical modernisation, a divide is also created between those who modernised (mostly metropolitan) and those who remained traditional (mostly rural). This became another area ripe for exploitation by the populists.

Nationalist versus globalist; middle class versus rich

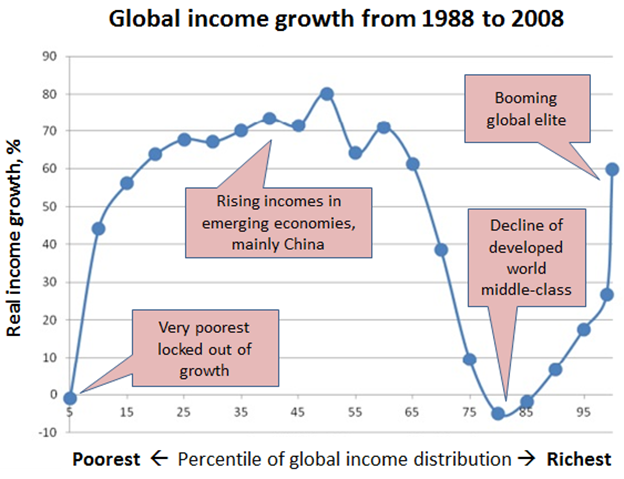

Globalisation and automation, by altering the world’s income distribution, played key roles in the recent rise of populism. Branko Milanovic’s famous Elephant curve (Figure 2) shows that, while the poorest of the developing countries and the lower and middle income groups of the industrialised countries realised only very little increase in their incomes since 1988, the middle and lower income classes of the developing world and the richest 1% of the world saw a big jump in theirs.

Figure 2: The Elephant curve

This gave rise to two new kinds of cultural populism, one pitting nationalists against globalists and the other pitting the middle class against the wealthy.

To get their support, both Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders relied on making the middle class feel like victims. Trump drew their attention to the back of the elephant; Sanders to the tip of its raised trunk. Trump presented Mexico, India and China, and immigrants from these countries as the victimisers, and Sanders the ultra-rich. To help the middle class, Trump offered reducing foreign trade and immigration, and Sanders proposed raising taxes on the incomes and wealth of the rich. In other words, Trump practiced right-wing populism and Sanders left-wing populism.

Several types of populism together

The conditions that give rise to different kinds of populism are different. But when these occur simultaneously, we observe more than one kind of populism. In particular, when one type of populism is insufficient to remain in power, leaders practice two or three populisms together, if the conditions are suitable.

For example, right now, governments in Hungary, Poland, Mexico, Turkey and many MENA countries are practicing economic, political and cultural populism, in Venezuela and Philippines, economic and political populism, and in Brazil, Russia, China, India, Myanmar and the UK, political and cultural populism.

Sometimes a factor can trigger or embolden more than one kind of populism. For example, economic populists used the Covid-19 pandemic as an opportunity to transfer funds to their supporters; political populists, to become more authoritarian and to discredit institutions and experts; cultural populists, to fan anti-globalist and anti-migrant sentiments.

Different types of populism feed each other, when they occur simultaneously, For example, when income inequality rises, the presence of migrants, minorities and large urban centres make it easier to practice not only economic populism but also cultural populism.

Then, natives and rural communities experience, in addition to feeling being surrounded by cultures alien to them, also a decline in their social status. This enables the populists to easily turn migrants, minorities and city dwellers into scapegoats for the real and imagined problems. The rise in income inequality, especially if it occurred unfairly, shakes people’s trust in the institutions. This too makes the practice of political populism easier.

Income inequality has been rising in the United States and Europe for some time. In the former, it has now reached a level almost the same as a century ago when anti-migrant, anti-minority and anti-foreigner feelings peaked, and resulted in severe restrictions being placed on immigration and foreign trade. This made it easier for leaders like Donald Trump and Boris Johnson to practice populism.

Let’s note that one type of populism may trigger another type. We know how authoritarian regimes have to use economic populism to stay in power. Now, we can state that economic populism often leads to political and cultural populism. Because the return from economic populism, to those who practice it, is positive in the short run but negative in the long run for staying in power, they eventually have to resort to authoritarianism. Often, they restrict the media and the opposition, and blame the migrants, minorities, international institutions and foreign powers for the declining economy.

What lies ahead?

The conditions for the growth of populism – such as the proportion of foreign-born people in the population, income inequality and lack of institutions that provide checks and balances – are not likely to change much in the short run. Thus, we should expect the current populist movements to be followed by other ones, left and right, as happened in the United States during the second half of 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century.