In a nutshell

Populists identify a segment of the society as the ‘real people’ and present themselves as their sole and genuine voice, fighting on their side against the elites and others who usurp their rights and benefits.

There are three kinds of populism: economic, political and cultural: although these have common characteristics, the conditions that give rise to each and their consequences are different.

Populism originated in the second half of the 19th century in the United States and Russia.

Economic populism involves pursuing social and economic policies that transfer resources from the wealthy to middle and lower income groups. These are initially popular with the public because, for most people, their benefits exceed their costs in the short run. But they are hard to sustain in the long run because their costs eventually exceed their benefits even for those who benefited from them in the beginning.

Political populism involves disregarding, undermining, capturing or getting rid of institutions in an authoritarian manner because they are viewed as barriers to ‘the will of people’ rather than providing checks and balances.

Cultural populism involves favouring a particular race, nationality, religion, sect or class, especially natives, as the ‘real people’, at the expense of others, especially migrants.

Although each of the three types of populism has different causes, they have many common characteristics. We will discuss the latter here and leave the former to two subsequent columns.

Characteristics common to all types of populism

Populists typically divide society into two groups, such as rich and poor, urban and rural, majority and minority, the proletariat and the bourgeoisie or natives and migrants. They label one of these as the ‘people’ and treat the rest as the ‘others,’ who usurp the rights of the people. They envisage these groups as being homogeneous and in conflict with each other.

Populists present themselves as the true voice of the real people, fighting for their rights and benefits against others and the elites who, for their own benefit, are aligned with others. Populists have an easier time convincing people of this when there are social groups with serious grievances. Common hostility towards ‘the other’ increases cohesion within the populist group.

Because populists see others as their enemy, and the economy as a ‘zero-sum game’, they refuse to compromise. They tend to gather under a charismatic and authoritarian leader and reject intermediary institutions between the people and their leader. They blindly follow the leader rather than letting a deliberative process guide them.

Similarly, populists do not trust experts and the media, and accuse them of trying to fool the people. Whenever it is possible, populist leaders restrict or control the mainstream media. When it is not, they reach the people directly through social media, bypassing the mainstream media.

For all of these reasons, populists tend to be anti-pluralist, illiberal, polarising and prone to believing and spreading conspiracy theories.

As in the cases of Donald Trump in the United States and Silvio Berlusconi in Italy, populist leaders may emerge from among the elites. Then, by acting crude, using vulgar and derisive language, and presenting their wealth as self-made, they try to appear as being part of the common people and not of the establishment.

Since it would be contradictory to claim to be the only legitimate representative of the people and to fail to win a majority at the ballot box, when that happens, as Trump experienced, populist leaders claim that corrupt elites have manipulated the vote behind the scenes.

Populism has a very thin ideology. To get it thicker, it has to be attached to an ideology with more depth. That is why we can talk of both right-wing and left-wing populism.

Although populists are a threat to democracy, they also serve a purpose by drawing attention to serious and long neglected problems, dysfunctional institutions and segments of the society that have been left behind.

But the simplistic solutions they offer are no remedies for these problems. Actually, their aim is not to solve problems but to exploit them in an opportunistic manner to attract supporters and to weaken institutions that check and balance their power.

Populist administrations and leaders may lose steam, often due to not delivering what they promised and the backlash they have generated. But by the time they leave office, they are likely to have caused severe damage to the economy, democratic institutions and unity of their countries, and have infected mainstream political parties with populism.

Origins of the term

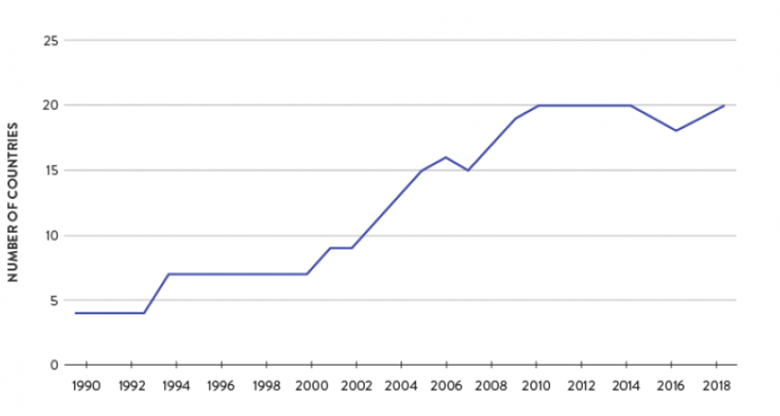

Populism is not something new. It emerged in the second half of the 19th century in the United States and Russia. But now, it is far more widespread and in power in many countries (see Figure 1).

The origin of the term ‘populism’ goes back to the People’s Party or the Populist Party, as it was called by the public. This party was established in the United States in 1892 and lasted until 1908. It practiced left-wing populism and fought the federal government, east coast banks and railroad companies to serve the interests of Midwestern farmers.

To end the recession and to reduce the real debt of farmers, the party advocated an inflationary monetary policy, and to accomplish that, abandonment of the gold standard. The party received 8.5% of the votes in the 1892 presidential election. After supporting the Democratic Party’s candidate in the 1896 presidential election, who offered similar policies, the party began its decay.

Until the mid-1950s, the word ‘populist’ was used by historians to refer to the Populist Party, but later, it became a term used by social scientists to describe all anti-elite and anti-establishment movements. Now, populists refrain from referring to themselves as populist because the word became a derogatory term used by others.

The Populist Party was not the first populist movement but the first one to call itself that. During the period 1849-60, a right-wing populist movement emerged in the United States, known as the ‘Know Nothings’, which was anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant and believed in white Protestant supremacy.

The Know Nothings operated as a secret society until 1854 and legally after that date, as the American Party. The party won five Senate and 43 House seats in the 1854 congressional election and 21.5% of the popular vote in the 1856 presidential election. But it joined the Republican Party before the next presidential election.

The Greenback Party, which functioned during the period 1874-84, was another populist party. Its vision was inherited by the Populist Party.

In the 1860s and 1870s, a populist movement emerged in Russia as well, which was called the Norodniki (the people). It championed rural interests and encouraged villagers to revolt against the tsar to form a socialist regime.

In two columns that will follow this one, we will show that the conditions prevailing today bear a strong resemblance to those that existed in the United States more than century and a half ago and which led to several populist movements.