In a nutshell

While digital technologies have spread rapidly in MENA countries, the broader development benefits from using them – the ‘digital dividends’ – have lagged behind: the opportunities offered by e-government are much wider than current usage.

Digital technologies are no shortcut to sustainable development: the digital economy also requires strong analogue components consisting of regulations, skills and institutions. Not undertaking necessary reforms in terms of digital complements will raise the opportunity cost.

The full benefits of the digital revolution will not be realised unless MENA countries continue to improve their business climate, invest in education and health, and promote good governance through strong institutions.

Both electronic governance (e-gov) and good governance have been widely discussed in the national and international arena. Digital technologies are some of the most transformational factors of our time, including their impact on effective governance and the process of sustainable development.

Public digital transformation has considerable potential for modernising public administration, improving public service delivery and promoting good governance. It may contribute to achievement of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set by the United Nations. In that regard, e-government initiatives remain an important driving force for realising this transition (EGOV4SD). It is becoming a viable alternative to the traditional bureaucratic means of public service delivery as it promotes open governance.

Digitalisation underpins every aspect of our daily life. Digital technologies – the internet, mobile phones and all the other tools to collect, store, analyse and share information digitally – have spread quickly and we find ourselves in the middle of the greatest information and communications revolution in human history (WDR, 2016).

The Covid-19 pandemic, which requires social distancing and quarantine measures such as lockdowns, has accelerated the role of digital government both in conventional delivery of digital services as well as new innovative efforts in managing the crisis. Digital solutions have become vital to address isolation and keep people informed and engaged (UN, 2020). E-governance ensures the delivery of services remotely, thereby reducing the economic, social and environmental costs associated with service delivery to the public.

Developing countries, including in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), have made efforts to leverage information and communications technologies (ICTs) over the past decade. Concerted efforts have been made to digitalise (fully or potentially) government services to the public.

But digital government efforts in the MENA region are still perceived as technical support activities and not as a core strategic component of public sector activities (OECD, 2017). The alternative would be that e-governance is value-driven instead of technology-driven.

Some stylised facts

In the MENA region, the level of achievement of SDGs, governance system performance and investment in advanced technologies are different from one country to another, including sometimes within the same state.

In terms of achievement of the SDGS, the region is facing many challenges in creating decent jobs, building constructive social dialogue and improving social justice. The uprisings in half a dozen countries in the region brought to light key challenges that had existed for some time such as low job creation, pervasive corruption and lack of accountability and transparency. The uprisings and their truncated aftermath raise many important questions about political reforms, especially in terms of institutional structures. Individuals are seeking to become active citizens.

Recently, the pandemic has exposed serious vulnerabilities in MENA societies, institutions and economies. The consequences of the pandemic are likely to be deep and long lasting and the region’s economy is expected to contract by 5.7% (UN, 2020).

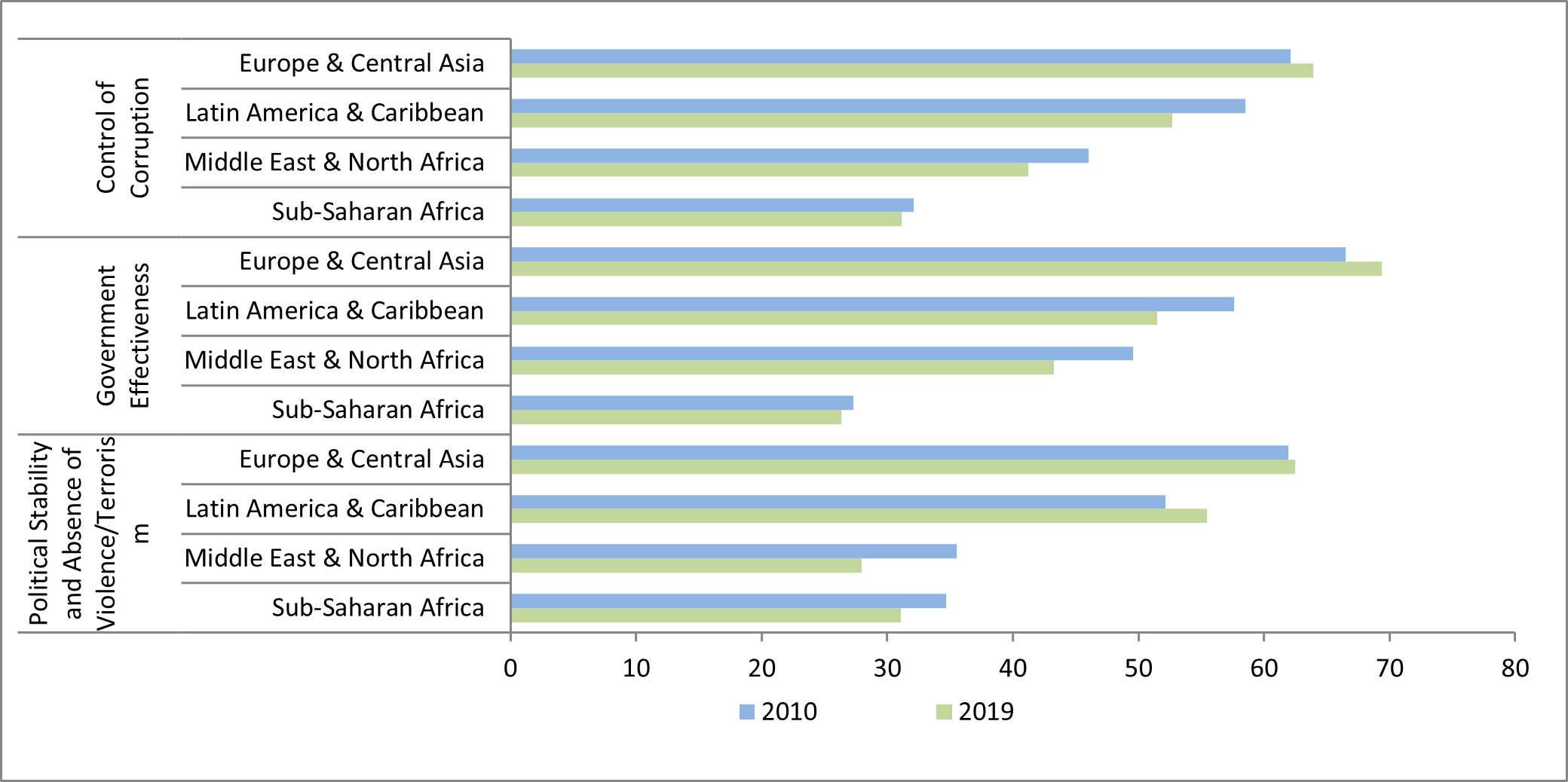

In terms, of governance system performance, adequate governance for innovation, and specifically ICTs, is severely lacking in most MENA countries (Göll and Zwiers (2018). There is a substantial cross-country variance in the related indicators, as well as variance in the responses to each of the indicators for individual countries.

Figure 1: Worldwide Governance Indicators (percentile rank*)

*Percentile rank (0-100) indicates rank of country among all countries in the world. 0 corresponds to lowest rank and 100 corresponds to highest rank.

Source: Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI).

Corruption remains a central challenge despite the work of many governments across the region to focus their national priorities on fighting corruption and increasing transparency. The corruption perceptions index, which ranks countries by their perceived levels of public sector corruption according to experts and business people, uses a scale of 0 to 100, where 0 is highly corrupt and 100 is very clean. With an average score of 39, the MENA region falls behind both the Americas and Asia Pacific regions (score: 44) and does only slightly better than Eastern Europe and Central Asia (score: 35) and sub-Saharan Africa (score: 32).

In terms of e-governance, the MENA countries are characterised by large public sectors and complex regulatory structures. The implementation of ICTs to modernise public institutions has emerged and is growing. But dividends seem to be limited. Digital and data skills are also still scarce and unevenly disrupted across territories. The budgetary constraint is another challenge for the implementation of digital government strategies (OECD, 2017).

The difference in levels of digital development in the MENA region is significant (Thunert 2009, UNDP 2012, ESCWA 2015, Chambers 2015). Indeed, the region encompasses a wide variety of trajectories within the economy (general preconditions, differences between oil-exporting countries and oil-importing countries, outsourcing, start-up cultures, etc.). Factors such as the distribution of basic infrastructure, enabling business culture, and supportive economic and education policies are very different between as well as within most countries (Göll and Zwiers, 2018).

According to the International Telecommunications Union (ITU), internet use ranges from 30% to 80% across the region, and there is a gender gap in favour of men in many countries. The gap is also between rural and urban areas in almost all countries of the region.

High-speed internet penetration is low compared with emerging regions in Europe and Asia. With the exception of Gulf countries, where internet access is available to broad segments of the population, in many countries of the Arab world fewer than a quarter of households have access to this essential tool. Millions of people cannot afford internet services and are therefore excluded from the ICT revolution that is shaping the modern world (Gelvanovska et al, 2014). Table 1 highlights the state of e-governance development by geographical region.

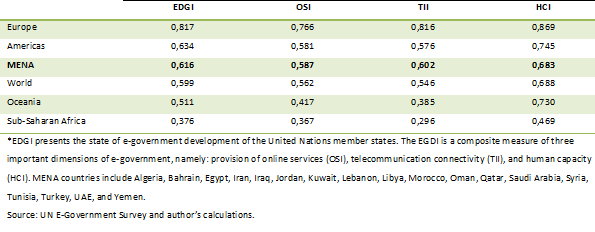

Table 1: Breakdown of EDGI* per geographical region (2020)

Europe continues to lead e-governance development as indicated by the highest EGDI (0.817) it enjoys, followed by the Americas (0.634), MENA countries (0.616), Oceania (0.511) and sub-Saharan African countries (0.376) respectively.

The Human Capital Index (HCI) is the highest contributing sub-index in MENA countries while the Telecommunication Infrastructure Index (TII) and online service (OSI) are the lowest. This suggests that the main hindrances to the further growth of e-government in the region are still the lack of infrastructure and the digital divide.

The question now is which of the three sub-indices the rise in EDGI in MENA countries comes from?

Figure 2: Contributors to the EDGI improvements

Source: Compiled by author.

Figure 2 indicates that the largest component of the rise in EDGI in the region comes from the improvement in TII. This implies that investment in telecommunication infrastructure is the fastest means of improving a country’s EGDI rankings. It is worth noticing also the importance of online services and human capital in the long run. Indeed, although improvements in both infrastructure and human capital have been slower, they are equally important for a healthy and functioning e-government system.

E-governance as an enabler of sustainable development

The issue now is how e-government initiatives can help MENA countries to achieve better results in their governance and therefore their development policy goals (EGOV4SD)?

EGOV4SD has been defined as the ‘use of ICT to support public services, public administration, and the interaction between government and the public, while making possible public participation in government decision-making, promoting social equity and socio-economic development, and protecting natural resources for future generations’ (Estevez and Janowski, 2013).

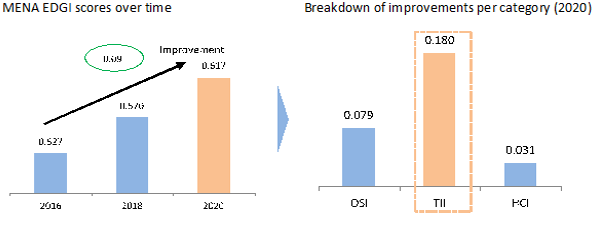

Policy-makers have two options: apply this strategy with or without implementation of good governance.

Figure 3: E-government, good governance and sustainable development nexus

Source: developed by the researcher.

The huge public investment in ICTs, in the absence of a good governance framework that embodies accountable institutions, enlarges the voice of the elite, which in turn can result in policy capture and greater state control. This situation can hinder the business climate by raising natural monopolies and therefore creating more concentrated markets.

In the absence of institutional reform, technology will fail to deliver the expected benefits in the region. E-government reforms face the risk of failure to be adequately embedded in public sector reform. As a result, progress on tacking social and environmental divides may be limited. E-government will exert an adverse effect on various aspects of sustainable development instead of being a catalyst for progress.

The digital governance framework in MENA countries still faces institutional difficulties despite the great achievements accomplished to date. Digital transformation also faces complex challenges from economic issues, social and political matters, to technology innovation and its diffusion patterns. These challenges remain heavily dependent on the development stage of each organisation and each country.

A conclusion that may emerge here is the inadequate impact of e-government on sustainable development in MENA countries (Dhaoui, 2020). Digital government efforts in the MENA countries are still perceived as technical support activities and not as a core strategic component for development corpus. As result, the impact of e-government initiatives on sustainable development will be limited in the region.

According to many studies and reports, and although ICTs have spread rapidly in much of MENA countries, digital dividends – that is, the broader development benefits from using digital technologies – have lagged behind. In many countries, the full potential of digital technologies is not being used. In many cases, e-government projects have enlarged opportunities and get better service delivery. But their aggregate impact has fallen short and is unevenly distributed. This proves the deficits in the adoption of new technologies in the MENA region vis-à-vis the major factors for success (Göll and Zwiers, 2018).

Adequate governance for e-government projects is severely lacking in most of the MENA countries. The region IS still unable to complement technology investments with appropriate economic reforms that reap digital dividends in the form of faster growth, better public services and adequate environmental management. These challenges are preventing the digital revolution from fulfilling its transformative potential in the region.

Access to ICTs and greater digital adoption is critical, but not sufficient. Thus, digital technologies are no shortcut to sustainable development; they can be an enabler by raising the necessary reforms. The digital economy also requires what the WDR (2016) calls ‘strong analog components’ which consisting of regulations that create vibrant businesses and let firms leverage digital technologies to compete and innovate, skills that allow workers to adapt to the demands of the new economy, and institutions that are accountable and that uses the internet to empower citizens.

Overcoming these challenges will require special awareness, commitment and a particular focus on ambitious and action-oriented strategies that contribute to bypassing e-government constraints and enhancing good governance, which in turn improves sustainable development and more inclusive societies.

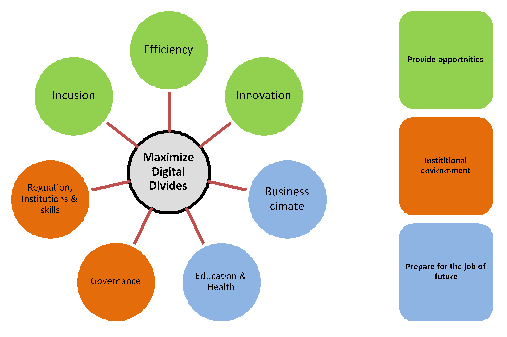

Figure 4: Digital governance components

Source: developed by the researcher.

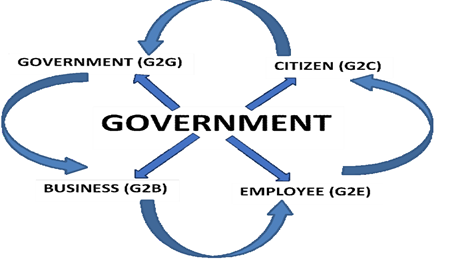

The role of governments is not only to act as facilitators and leaders; but also as enablers and regulators. Given the limited resources of governments, the involvement of stakeholders through transparent cooperation is crucial. Governments are consistently interacting with diverse interest groups across society such as citizens (G2C), employees (G2E), businesses (G2B) and various state agencies (G2G), cohesively.

Figure 5: The various interactions in E-government

Source: Alhassan, 2020. E-governance for sustainable development in Ghana: Issues and prospects.

Roadmap for successful e-government initiatives

In order to achieve economic, social and environmental sustainability for MENA countries, it is crucial to establish good governance by forming an institutional environment capable to enabling the government with more effective and efficient tools for more successful development plans. But the region suffers from a lack of adequate training and knowledge about the technology, access to it, and knowledge of how to best apply it.

Policies on the use of digital technologies need to be adequately embedded in public sector reform. MENA countries should promote competitive business environments, enhance accountability, and upgrade education and skills development systems to prepare people for the jobs of the future. The race is between skills and technology, while the outcome will settle on whether the dividends from ICTs are realised and the benefits widely shared.

Bringing digital technology and governance practices together at the forefront of sustainable development strategies and providing new and innovative technological options leading to improve governance strategies may contribute to achieving sustainable development in all dimensions.

A particular emphasis on building a digitally inclusive society is needed. The increase in access to digital technologies should bring more choice and greater convenience in the region. This can be done through inclusion, efficiency and innovation that are capable to provide opportunities that were previously out of reach to the poor and disadvantaged.

The full benefits of the ICT revolution will not be realised unless MENA countries continue to improve their business climate, invest in education and health, and promote good governance through strong institutions.

Figure 6: Pre-requisites for maximising digital dividends

Source: developed by the researcher.

The challenge is to start adequate reforms to maximise digital dividends and to prepare for any disruptions. The digital economy is changing rapidly. Not undertaking the necessary reforms in terms of digital complements such as regulation, skills and institutions will raise the opportunity cost. Any failure to reform will lead to a situation of falling farther behind those who do reform. Strengthening the interaction between technology and its complements is more urgent than ever before.

Further reading

Chambers, J (2015) ‘How Technology Is Transforming the Middle East’, World Economic Forum.

Dhaoui I (2020) ‘E-Government for Sustainable Development in MENA Countries’, ERF Working Papers No. 1424.

ESCWA (Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia) (2015) ‘Role of Technology in Sustainable Development in the Arab Region’.

Estevez E, T Janowski and Z Dzhusupova (2013) ‘Electronic Governance for Sustainable Development – How EGOV Solutions Contribute to SD Goals?’, Proceedings of the 14th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research.

Gelvanovska, N, M Rogy and CM Rossotto (2014) ‘Broadband Networks in the Middle East and North Africa: Accelerating High-Speed Internet Access. Directions in Development–Communication and Information Technologies’, World Bank.

Göll E, and J Zwiers (2018) ‘Technological trends in the MENA region: the cases of digitalization and Information and Communications Technology (ICT)’, MENARA Working Papers No. 23.

OECD (2017) ‘Benchmarking Digital Government Strategies in MENA Countries’, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing.

Thunert, M (2009) ‘The Information and Decision Support Centre (IDSC) of the Egyptian Cabinet: A Think Tank in the Making’, in Zeitschrift für Politikberatung 2(4): 679-84.

UN (United Nations) (2020) ‘The Impact of COVID-19 on the Arab Region: An Opportunity to Build Back Better’, Policy brief.

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme) (2012) ‘Arab Knowledge Report 2010/2011: Preparing Future Generations for the Knowledge Society.

WDR (World Bank Development Report) (2016) ‘Digital Dividends’, World Bank.