In a nutshell

MENA countries have lower levels of taxation, as indicated by tax-to-GDP ratios, than those in other regions; they also rely more on indirect taxes with particularly low reliance on income, profits and capital gains taxes.

GCC countries experienced higher volatility in tax revenues in the 2008 recession compared with other parts of the region, which was driven by a decline in tax revenue from international trade.

For the post-pandemic period, the region needs tax reform to build better tax capacities to respond to crises, to address rising inequality by increasing reliance on income taxes (and lowering consumption taxes), to lower reliance on international trade taxes that cause revenue volatility especially in oil-exporting countries, and to decentralise tax systems while improving coordination between central and local governments.

The global pandemic has had a profound impact on the countries of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). While some responded relatively well in mitigating impact and limiting the spread of Covid-19, there will still be immense, long-lasting economic shock in the region.

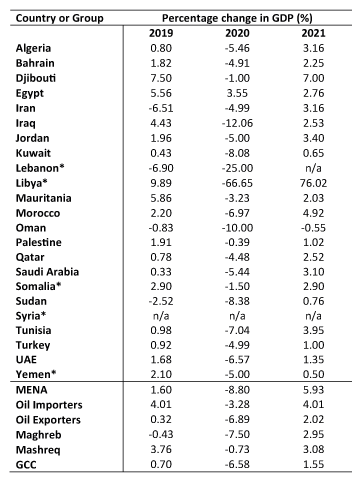

As data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) October 2020 World Economic Outlook Database projections in Table 1 show, the MENA economies are expected to contract by 8.8% in 2020 – compared with 1.6% growth in 2019 – due to the economic implications of the pandemic. While many of the oil-exporting countries in the region are expected to experience some economic rebound in 2021, other MENA countries lacking significant oil reserves and economic buffers will have a longer road to recovery.

A number of countries in the region, especially the members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), have significant oil resources. This characteristic affects the tax structure by allowing many governments to depend disproportionately on oil income to maintain government revenue levels and form narrow tax bases (Mansour, 2015). As a result, many governments in this region lack resilience in their tax structure and risk being disproportionately affected by any shocks to the global oil market, such as with the current pandemic and economic crisis.

Much as with the 2008 Great Recession, governments will have the ability to help or hinder their economic recovery process through crafting fiscal policy measures. But government responses in MENA will be significantly limited by funding and whether or not governments manage to maintain reasonable levels of revenue throughout this crisis.

A recent commentary on Covid-19 and taxation in the region (Gaspar et al, 2020) stresses that ‘it is important that we do not lose sight of the imperative to support longer-term tax capacity building, and the importance of mobilising revenues in the aftermath of the crisis… needed to restore fiscal sustainability… Taxes will play a role in shaping the “new normal”.’

Composition of tax revenues

A good first step in understanding the tax structures in the MENA region is to examine the composition of tax revenues (see Tosun, 2005, for an analysis of the changes in the tax composition of MENA countries in response to trade liberalisation).

Given the difficulty in obtaining complete, consistent tax revenue data in the region, we use averages over the 2010-15 period to include as many countries in the analysis as possible. The UNU-WIDER GRD Database served as the primary data source and the IMF Government Finance Statistics and the World Bank’s World Development Indicators were used to account for any additional available data not included in the UNU-WIDER database. We present data in Table 1.

Table 1: Recent and projected changes in GDP in MENA countries

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook Database, October 2020. * countries with serious conflicts and fragile states.

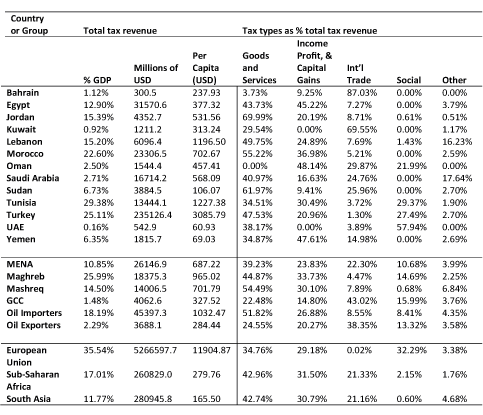

Largely due to its additional revenue sources from resource wealth, MENA maintains the lowest tax revenues as a percentage of GDP rate among its neighbouring geographical regions – see Table 2. Similarly, MENA has by far the smallest total tax revenue (in dollars), even though it maintains higher tax revenues per capita than South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

Table 2: Composition of tax revenues in the MENA countries and in neighbouring geographical regions (average shares for 2010-2015)

Source: UNU-Wider GRD Database (https://www.wider.unu.edu/project/government-revenue-dataset), International Monetary Fund (https://data.imf.org/?sk=a0867067-d23c-4ebc-ad23-d3b015045405), World Bank (http://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/).

Within the region itself, oil importers are significantly more dependent on taxes to maintain general government revenue levels than oil exporters. Tax rates for importers comprise 18.19% of total GDP, but only 2.29% for exporters. Even more drastically, GCC countries collect just 1.48% of their GDP in total tax revenue, compared with the Maghreb region’s 25.99% and the Mashreq region’s 14.50%.

It is important to note, however, that this wide disparity shrinks somewhat when tax size is compared in real US dollars. Oil-exporting countries tend to have much larger economies, so while importers’ tax revenues as a percentage of GDP are nearly eight times higher than exporters, they still only take in roughly 4.25 times more tax revenue in real US dollars.

Despite this, the over-reliance on resource revenue is a distinct vulnerability within the government revenue structures of MENA countries. Exporter countries have very low levels of taxation due to their resource wealth, but even the taxes they do have still share strong dependency on the hydrocarbon industry.

While international trade taxes account for just 8.55% of total tax revenue for oil importers, they comprise nearly 40% of total tax revenue for exporters – much of which is built around additional taxes on oil exports. This is especially worrying because oil exporters are already extremely vulnerable to an often-volatile oil market to maintain non-tax government revenues.

Although many oil-exporting countries have been reluctant to diversify their government revenue structures, in the wake of the pandemic, the rapid decline of the oil industry is causing total government revenue numbers in MENA countries to plummet. The global crisis has produced simultaneous supply and demand shocks in the oil market, presenting a worst-case scenario for the risks that oil exporters in particular have taken in their over-reliance on hydrocarbon revenue.

In response to the economic uncertainty created by Covid-19, taxes will be a vital revenue stream to help to maintain the stability and presence of governments in the region as they face the repercussions of this global pandemic. Furthermore, as MENA countries rebuild their countries in a post-Covid-19 world, many are more likely to begin earnestly considering how to diversify their revenue sources and increase their tax bases.

Presently, the general tax structure in the MENA region most heavily relies on the goods and services category, which comprises 39.23% of total tax revenue, followed by income, profit and capital gains, which sits at 23.83%.

At 22.30% for the general region, international trade is oil-exporting countries’ largest source of tax revenue, but it also sits at only 8.55% for oil importers. Social taxes make up an additional 10.68% of revenue, followed by other taxes at 3.99%. Property taxes, which are combined into the other category in Table 1, make up a near-negligible percentage of total tax revenue.

The region’s tax structure mainly differs from its neighbouring country aggregates with its consistently lower income, profit, and capital gains tax percentage, especially among oil-exporting countries. The international trade tax percentages rank similarly among MENA, sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, but the EU almost entirely lacks tax revenue in that category. Furthermore, while the MENA countries do not meet the EU’s 32.29% in the social security contributions category, their reliance on those taxes is still higher than sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia’s near-zero numbers.

Tax revenue changes during the 2008 recession

The 2008 recession is a good historical comparison for tax revenue contraction in a Covid-19-like situation of rapid, global economic contraction. Mirroring the current crisis, MENA countries were forced to weather this recession from late 2007 through 2009 while also experiencing plummeting oil prices, most notably manifested in the 2007/08 oil shock. Because of the parallels of these two crises, historical data from the 2008 recession could illuminate possible contractions, volatility and patterns that might reoccur in the wake of the pandemic and economic crisis.

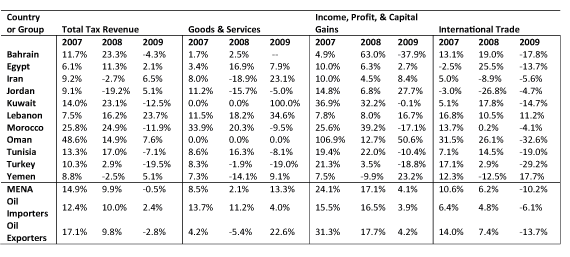

Table 3 shows that of all the tax categories, the international trade tax experienced the sharpest decline in revenue during this period. Revenue contraction reached as high as -13.70% among oil exporters and -6.06% among oil importers in 2009, averaging -10.23% for the region as a whole.

Table 3: Percentage change in tax revenue for MENA during the 2008 Great Recession

Source: UNU-WIDER GRD Database (https://www.wider.unu.edu/project/government-revenue-dataset), International Monetary Fund (https://data.imf.org/?sk=a0867067-d23c-4ebc-ad23-d3b015045405).

This volatility is especially worrying for oil exporters, which are already over-dependent on the international trade tax for almost 40% of total revenue. If the hydrocarbon market falls – as is the case in the economic crisis from Covid-19 – exporters experience a double-whammy of revenue loss from both general resource revenue and the largest revenue stream in their tax base.

Due in part to this large vulnerability, Table 3 shows that oil exporters experienced revenue contraction more immediately than importers. In 2007, oil importers experienced a 12.35% increase in total tax revenue, followed by 10.03% in 2008, and finally a large decrease in growth down to 2.38% in 2009.

In contrast, oil exporters had a downturn earlier, going from 17.08% growth in 2007 to 9.84% in 2008, followed by a further contraction of 2.84% in 2009. The income, profit, and capital gains tax follows a similar pattern, as does the international trade tax.

This historical pattern of oil importers having a lag in economic contraction in tax revenue is consistent with predictions for MENA countries in the pandemic. For oil-exporting countries, Jihad Azour, writing at The Forum, anticipates that ‘lower export receipts [from the falling oil market] will weaken external positions and reduce revenue… Oil importers, on the other hand, will likely be affected by second-round effects, including lower remittance inflows and weaker demand for goods and services from the rest of the region.’

This expectation concerning the goods and services category also holds with the historical data. While oil exporters were hit with a -5.42% contraction for goods and services in 2008, oil importers maintained a stable 11.30% growth in 2008, compared with the 13.70% rate experienced in 2007. But this pattern changed in 2009, when growth dropped to 3.97% for oil importers but bounced back by 22.63% for oil exporters. This illuminates another economic aspect of the region: oil importers will probably have a harder road to economic recovery and may maintain sluggish levels of growth in a post-Covid-19 world.

MENA importers had this very issue in their recovery from the 2008 recession because they lacked (and still do lack) ‘a sufficient number of export partners and are now vulnerable to the slowdown in advanced countries,’ particularly the GCC and the EU. While importers will likely experience a lag in direct economic contraction from the Covid-19 pandemic, their dependency on other countries’ economic conditions will also create a lag in their recovery process (Achy, 2010).

Tax policy options

The MENA countries have lower tax-to-GDP ratios than those in other regions including the EU, sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. This is mainly driven by a very low level of taxation in the GCC countries. There is significant variation across different parts of the MENA region with the highest tax-to-GDP ratio in the Maghreb region.

The three most important taxes for the MENA countries are taxes on goods and services, taxes on income, profits and capital gains, and international trade taxes, with significantly lower reliance on taxes on income, profits and capital gains compared with other regions. The reliance on social security taxes is also much smaller compared with the EU countries. There has been more volatility in tax revenues in response to the 2008 recession in oil-exporting (GCC) countries. This is mainly driven by changes in international trade tax revenue.

Moving forward, the MENA countries need to build better tax capacities to respond to crises such as the pandemic and rising debt levels. There is room for those countries to increase their taxes on income (and lower taxes on consumption) to raise more tax revenue and at the same time address the rising inequality in the region, which is likely to get worse due to the pandemic (Abdo and Almasri, 2020, United Nations, 2020).

A heavier reliance on income tax could significantly raise tax revenues especially if the MENA countries are successful in raising productivity through job opportunities for their relatively young populations and higher labour force participation of women in the region. Investing in workforce development will indeed help in terms of tax revenue generation. Oil-exporting countries would benefit from lowering their reliance on international trade taxes that cause revenue volatility for those countries.

Finally, the MENA region has a very centralised government structure, driven by its history, institutions and conflicts (Tosun and Yilmaz, 2010; Tosun, 2014). While the countries in the region have a variety of local governments, there is little fiscal autonomy at the local level, which limits any quick response by local governments (Tosun, 2011).

The region would benefit from fiscal decentralisation while strengthening coordination between central and local governments. There are examples where better central-local coordination has produced better outcomes in terms of government response to the Covid-19 crisis (Huynh et al, 2020).

Further reading

Abdo, Nabil, and Shaddin Almasri (2020) ‘For a Decade of Hope Not Austerity in the Middle East and North Africa: Towards a Fair and Inclusive Recovery to Fight Inequality’, Oxfam International.

Achy, Lahcen (2010) ‘MENA Oil-Importing Countries: Great Challenges Ahead’, Carnegie Middle East Center.

Gaspar, Vitor, and colleagues (2020) ‘Facing the Crisis: the Role of Tax in Dealing with COVID-19’, IMF.

Huynh, Dat, Mehmet Tosun and Serdar Yilmaz (2020) ‘All-of-Government Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Case of Vietnam’, Public Administration and Development.

Mansour, Mario (2015) ‘Tax Policy in MENA Countries: Looking Back and Forward’, IMF Working Paper, Fiscal Affairs WP/15/98.

Tosun, Mehmet (2014) ‘Centralization Government Structure in the Middle East and North Africa Region: A Historical Perspective’, The Maghreb Review 39(4): 458-65.

Tosun, Mehmet (2011) ‘Middle East and West Asia’, in Local Government Finance: The Challenges of the 21st Century, Second Global Report on Decentralization and Local Democracy, United Cities and Local Governments.

Tosun, Mehmet, and Serdar Yilmaz (2010) ‘Centralization, Decentralization and Conflict in the Middle East and North Africa’, Middle East Development Journal 2(1): 1-14.

Tosun, Mehmet (2005) ‘The Tax Structure and Trade Liberalization of the Middle East and North Africa Region’, Review of Middle East Economics and Finance 3(1): 21-38.

United Nations (2020) ‘Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on the Arab Region: An Opportunity to Build Back Better’.