In a nutshell

Elites in Lebanon must commit to a new reform agenda to increase citizens’ trust in its government, including taking on corruption and abuse of public offices.

Strong and universal social safety nets must decrease the dependency of citizens on communal elites.

International actors need to learn from past experiences by proposing aid and support programmes contingent on a set of reforms that are actually implementable and generate a purpose for citizens’ struggle.

Lebanon is facing a perfect storm. Long in the making, overlapping economic, financial and banking crises have come to threaten Lebanon’s political, economic and social stability.

This stability relied on an elite-level consensus for inter-sectarian power-sharing, distributing patronage and excessive economic rents to the respective clients. Eventually, this social contract became too costly to sustain (Mahmalat and Chaitani, 2020; Diwan and Chaitani, 2015).

As poverty rates soar, purchasing power plunges and foreign funds dry up, Lebanon’s political elites now face the ruins of a 30-year political legacy of heedless over-appropriation of rents. And it is the disaster in neighbouring Syria, despite the countries’ differences, which provides insights for Lebanon into how grievances can accumulate to a point at which single events can trigger conflict.

Uncanny parallels

Three of the main challenges that plagued Syria in 2010 and Lebanon today are awkwardly similar: worsening socio-economic grievances; decreasing life satisfaction; and a deep distrust into state institutions. In Lebanon, these grievances precipitated the eruption of the October 2019 popular uprisings, which, amid periodic mass protests since then, illustrate the widespread dissatisfaction with the prevailing social order.

In Syria, these challenges pushed millions onto the streets in the early days of 2011, demanding, among many other things, better living conditions and just governance. As the ties between citizens and elites eroded, protests ultimately became uncontrollable. Eventually, elites calculated that they had few choices other than a flight forward by using war to maintain their grip on power.

In the absence of a credible reform programme that redistributes wealth, increases trust in governments and opens economic opportunities, Lebanon’s elites too might come to see its alternatives diminished.

Socio-economic grievances

Socio-economic grievances in Syria in 2010, as well as in Lebanon in 2020, were and are horrendous (Brück et al, 2007). Syria’s poverty rates of about 30% (upper bound based on real consumption) in 2010 appear almost desirable against recent projections of 42% in Lebanon – even before the Covid-19 crisis hit and the lockdown exacerbated a projected recession of more than 12% in 2020. Vertical and horizontal inequalities will increase in what is already one of the most unequal societies worldwide (Assouad et al, 2018).

Large and unsustainable budget deficits threaten macroeconomic stability in both countries. Syria’s non-oil budget deficit amounted to 10.2% of GDP in 2006. As oil revenues continued to decline, Syria had to end massive subsidies, especially for fuel. The reduction of these subsidies in turn raised prices for bread as Syria literally had grown wheat in the desert, using cheap fuel to irrigate its fields.

Lebanon’s perennial budget deficit of an estimated 11.3% in 2019 places similar strains on transfers to the country’s energy company, Electricité du Liban. After Lebanon’s first formal default in history in March 2020, external financing via private sources is similarly constrained as in sanctioned Syria. Projections for inflation have reached long-avoided levels of 53% in 2020 due to the relative scarcity of imports, adding another regressive tax on top of an already unfair taxation system (Mahmalat and Atallah, 2018).

Speaking of taxation, widespread corruption and inefficiencies in revenue collection deprive citizens in both states of opportunities to ensure a fair distribution of wealth and income. In Syria, tax revenues only represented roughly 10% to GDP, while Lebanon’s similarly small 13.6% in 2015 still ranks well below the average of peer countries worldwide (16.4%).

Not only does unfair taxation and large-scale tax evasion benefit the already wealthy, it places additional burdens on the poorer and middle classes by depriving them of opportunities to formalise their businesses, to benefit from social protection schemes or to receive quality public services such as health and education.

Over time, mechanisms for compensating citizens for such systematic disenfranchisements – in particular the use of public sector employment and the redirection of public resources for clientelist services – became unsustainable. But when connections trump merit in public hiring, quality and adaptivity decline.

In Syria, the public sector snapped up some 28% of the working population before the war, placing a heavy burden on public expenditures and inhibiting efficient service delivery. In Lebanon, the public sector employs roughly 30% of the working population for delivering public services that necessitate privatisation in virtually every domain of social life, from electricity to education (Sanchez, 2018).

Still, personnel costs in public administration were the fastest rising budget item after 2008 (Mahmalat and Atallah, 2018) and came to consume more than a third of total expenditures in 2019. While even two hiring freezes in 1996 and 2017 could not halt the abuse of public sector employment via alternative schemes (Salloukh, 2019), inflation as well as the inability of Lebanese state institutions to pay its dues and wages came to place a natural limit on the attractiveness of public employment as a patronage tool.

In addition to these developments, the continuous presence of large refugee communities (Iraqis for Syria in 2010, and Palestinians and Syrians in Lebanon today) significantly increase communal tensions and distributional conflict over scarce public resources, with little prospect for improvement.

In Syria in the late 2000s, Iraqi refugees were both welcomed as ‘brothers’ and simultaneously expected to return home swiftly (Brück et al, 2007). Given the insecurity in Iraq at the time, a return of refugees was unlikely and only changed after the war started in Syria itself. Likewise, the prospects of Syrian refugees in Lebanon returning any time soon will remain unrealistic unless security in Lebanon becomes worse than in Syria.

Decreasing life satisfaction

The outlook for economic opportunities is similarly bleak. Inefficient bureaucracies mean high costs to start and maintain businesses. Dismal labour productivity in key sectors, persistently low investment rates, lack of access to finance and unfair competition from connected firms depressed beliefs in a better future for Syrians in 2010, as they now do for Lebanese people in 2020.

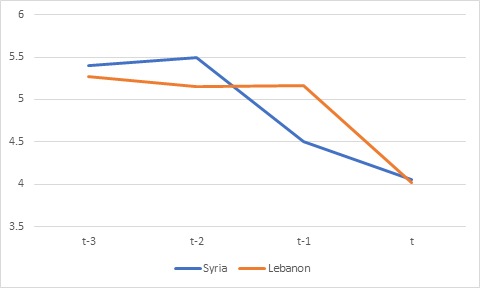

A Gallup poll in November 2019 finds that only 5% of respondents in Lebanon perceive living conditions to be improving. Accordingly, life satisfaction decreased significantly. On the so-called ‘Cantril ladder’, a widely used ten-point scale to measure satisfaction where 10 represents the best possible life for an individual, life satisfaction dropped for Syrians from 5.4 in 2008 to 4 in 2011 (Devarajan and Ianchovichina, 2018), while it dropped similarly from 5.3 in 2016 to 4 in 2019 for Lebanese (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Life satisfaction in Lebanon from 2016 to 2019 and Syria from 2008 to 2011.

(Source: Gallup)

Lack of trust in institutions

It is this bleak outlook that constitutes the potentially even more important challenge. The lack of belief in a positive future has undermined the credibility of politicians and led to a significant decline of trust into governmental institutions.

In Syria, few investors and international institutions bought into the sustainability of the reform agenda prior to 2011 in light of the deep entrenchment of the regime with the rentier economy of the state. In Lebanon, the same can be said about elites’ willingness to reform (Mahmalat and Atallah, 2019), as continuous inertia to reform deprives its citizens from reaping the benefits of multi-billion donor programmes (LCPS 2019).

Accordingly, trust in governmental institutions has plummeted in Lebanon (Fakih et al, 2020). The Arab Barometer from 2018 finds that less than 20% of citizens trust governmental institutions to a great or medium extent, while the same Gallup poll from November 2019 finds this ratio to have decreased to only 15% for Lebanon.

The magnitude of socio-economic crises is not only assessed based on the deterioration of purchasing power or poverty rates. It is fundamentally the frustration about leadership and lack of opportunities that drives protests and eventually makes them unpredictable (Devarajan and Ianchovichina, 2018).

In Syria, budget constraints have constrained elites from distributing rents to constituencies in the late 2000s that could have offered economic opportunities. Lebanon’s clientelist networks will not remain unscathed either.

As traditional means of rent extraction and allocation ceased in effectiveness or simply stopped to function all together (Mahmalat, 2020), maintaining networks based on economic benefits, such as via healthcare or public sector projects and employment, will reduce its marginal value over time. Fear-based mechanisms (Paler et al, 2018) are likely to fill the void, as they did in Syria.

Covid-19

The pandemic only accelerates these developments. Covid-19 and the lockdown have increased poverty, weakened public finances, exposed government corruption, reduced life satisfaction and prevented refugees from returning home. And in doing so, it will further reduce trust in political institutions, even as political leaders in Lebanon rush to exploit the crisis to cement the dependency of their constituencies, opening the door for further polarisation and exclusion.

It is precisely these ingredients – increasing inequality, intercommunal antagonism, dependency on elites that aim to maintain their popular support, and decreased opportunity costs of violence due to the reduction of purchasing power – that can lead to armed conflict (Cederman et al, 2013). Despite the lockdown, the Lebanese police have already had to disperse protests over poor living conditions and lack of economic relief measures.

Looking ahead

Another lesson from the Syrian crisis is this: once the genie is out of the bottle, running him down is tough. As leaders start playing the fear-card to structure interactions with their constituencies, negative shocks leave them with limited political space for manoeuvre.

In Syria, the reduction in fuel subsidies deprived millions of subsistence income, creating socio-economic repercussions that the social welfare systems were ill-equipped to cope with and easing the way for blame-shifting and polarisation. To the extent that Lebanese farmers are unable to till their fields due to confinement or exchange reserves drying up, additional food price shocks threaten to hit in several months’ time.

In the absence of a credible silver lining that offers political and economic opportunities, such as a credible reform programme supported by the International Monetary Fund, elites might calculate that they are left with little alternative than another flight forward into violence.

The longer the economic crisis lasts, the more the opportunity costs of violence will decrease and the cheaper it gets for warlords to pay militias. The Lebanese army might abstain from shooting down peaceful protesters, as the Syrian army did in 2011. But as protests turn violent, fear ultimately makes the interaction between communities unpredictable.

To spare Lebanon Syria’s fate, three points are crucial by which Lebanon’s elites – with the help of international actors – must create a silver lining to give citizens hope and an object to legitimise their struggle:

- First, elites must give costly signals about committing to a new reform agenda to increase citizens’ trust in their government, such as by taking a stand against corruption and abuse of public offices.

- Second, strong and universal social safety nets must decrease the dependency of citizens on communal elites.

- Third, international actors need to learn from past experiences (Atallah et al, 2018) to propose aid and support programmes contingent on a set of reforms that are actually implementable and generate a purpose for citizens’ struggle.

If there is only one lesson from the Syrian disaster, it’s that it is better be serious about reform.

Further reading

Lydia Assouad, Lucas Chancel and Marc Morgan (2018) ‘Extreme Inequality: Evidence from Brazil, India, the Middle East, and South Africa’, AEA Papers and Proceedings 108: 119-23.

Sami Atallah, Mounir Mahmalat and Sami Zoughraib (2018) ‘CEDRE Reform Program: Learning from Paris III’, Lebanese Center for Policy Studies Policy Brief.

Tilman Brück, Christine Binzel and Lars Handrich (2007) ‘Evaluating Economic Reforms in Syria’, Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung, Berlin.

Lars-Erik Cederman, Kristian Skrede Gleditsch and Halvard Buhaug (2013) Inequalities, Grievances, and Civil War, Cambridge University Press.

Shantayanan Devarajan and Elena Ianchovichina (2018) ‘A Broken Social Contract, Not High Inequality, Led to the Arab Spring’, Review of Income and Wealth 64(S1): 5-25.

Ali Fakih et al (2020) ‘Confidence in public institutions and the run up to the October 2019 uprising in Lebanon’, Working Paper.

LCPS, Lebanese Center for Policy Studies (2019) ‘The Government Monitor No. 7: Lebanese Government: A Dismal Performance’.

Mounir Mahmalat (2020) ‘Balancing Access to the State: How Lebanon’s System of Sectarian Governance Became Too Costly to Sustain’, Lebanese Center for Policy Studies, forthcoming.

Mounir Mahmalat and Sami Atallah (2018) ‘Why Does Lebanon Need CEDRE? How Fiscal Mismanagement and Low Taxation on Wealth Necessitate International Assistance’, Lebanese Center for Policy Studies Policy Brief.

Mounir Mahmalat and Sami Atallah (2019) ‘Recession without Impact: Why Lebanese Elites Delay Reform’, The Forum.

Mounir Mahmalat and Youssef Chaitani (2020) ‘Post-Conflict Power Sharing Arrangements and the Volatility of Social Orders – The Limits of Limited Access Order in Lebanon’.

Laura Paler, Leslie Marshall and Sami Atallah (2018) ‘The Fear of Supporting Political Reform’, Lebanese Center for Policy Studies No. 31.

Bassel Salloukh (2019) ‘Taif and the Lebanese State: The Political Economy of a Very Sectarian Public Sector’, Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 25(1): 43-60.