In a nutshell

Rates of internal migration in Egypt are low: in 2012, only 21% of adults lived in a different village or neighbourhood from the one in which they were born.

Internal migration rates peak at around the age of 25, at a migration rate of slightly less than 0.7% per year.

The children of rural to urban migrants stay in school longer and are more likely to complete secondary or higher education than the children of those who remain in rural areas.

Internal migration can provide new and better educational opportunities, but it can also interrupt education (UNESCO, 2019). Whether internal migration helps or hinders education depends on educational policies, the availability and quality of schools, and the social and economic changes that migrants may experience. Egypt is a country with low internal migration rates; out of 61 countries, Egypt has the second lowest rate of internal migration (Bernard et al, 2019).

Migration in Egypt is predominantly from rural to urban areas (Wahba, 2007; David et al, 2019). Migrants tend to settle in informal urban areas (slums), areas which have challenges in access to and quality of services (Zohry, 2002; Sieverding et al, 2019).

But legally, children can access services such as education so long as they have an identification card (Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, 2019). An important question we investigate is how internal migration ultimately affects educational outcomes (Krafft et al, 2019a).

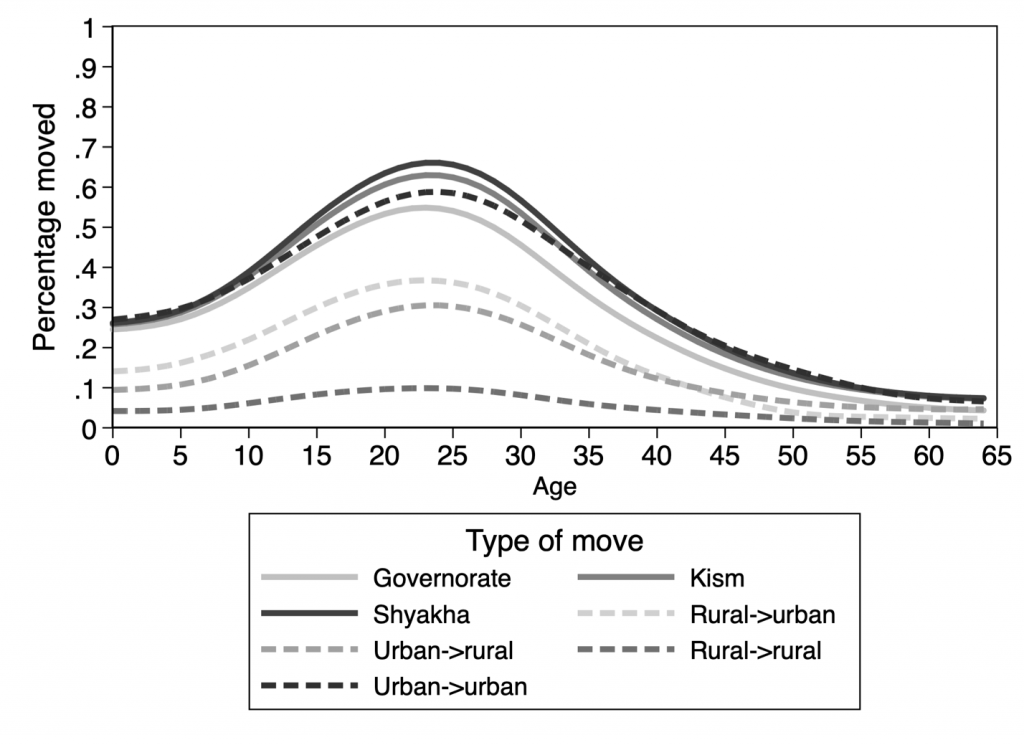

Internal migrants in Egypt are primarily adults. Figure 1 shows annual migration rates by age and type of move. In Egypt, the first level of administrative geography is a governorate, the second a ‘kism’ (district) and the third a ‘shyakha’ (village or neighbourhood).

Moves are, of course, more common when we look at lower levels of geography. We also measure dynamics between urban and rural areas, for those who started in a particular location (for example, rural to urban migration is based on those initially in rural areas). Migration rates are low for children and peak around the age of 25, when slightly less than 0.7% of individuals migrate per year.

Figure 1: Annual migration rates (percentage) by age and type of move

Source: Krafft et al (2019a) based on Egypt Labor Market Panel Survey (ELMPS) 2012.

Source: Krafft et al (2019a) based on Egypt Labor Market Panel Survey (ELMPS) 2012.

Education is rarely the reason for internal migration. Primarily, Egyptians migrate to be with family, to marry (especially women) and to work (especially men) (Krafft et al, 2019a). But migration can still affect education, even if it is not the reason for migration. In particular, when adults migrate to work and marry, their subsequent children may face different educational opportunities.

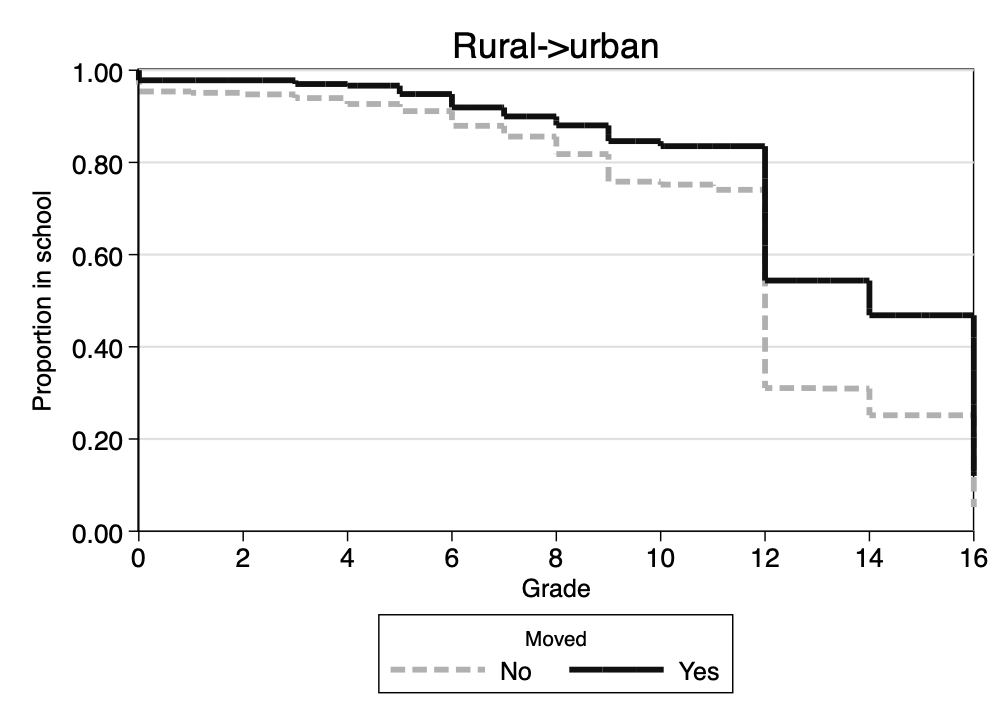

Figure 2 shows how persistence in school varies by mother’s migration status, for children whose mothers were born in a rural area. In Egypt, almost all children start school. The proportion of young people in school declines a bit through primary (grades 1-6) and preparatory (grades 7-9) education. Children whose mothers moved from rural to urban areas are slightly more likely to enter school and persist through primary and preparatory education than children whose mothers remained in rural areas.

There is substantially more dropout among children whose mothers remained in rural areas at the end of grade 9, the transition to secondary school (grades 10-12). There is a particularly large difference in continuing into higher education (grades 13-16); more than half of children whose mothers migrated to urban areas went on for higher education, but less than a third of those children whose mothers remained in rural areas. The outcomes for the children of rural to urban migrants are the same as other children in urban areas (Krafft et al, 2019a).

Figure 2: Proportion persisting in school by grade and mother’s rural to urban migration status, mother born in a rural area

Source: Krafft et al (2019a) based on ELMPS 2006 and 2012 panel.

Source: Krafft et al (2019a) based on ELMPS 2006 and 2012 panel.

Notes: Kaplan-Meier survival function.

Although Figure 2 shows that children whose mothers migrated stayed in school longer and attained higher levels of education, was this change caused by migration? We know that adults who are more educated tend to migrate more in Egypt (Krafft et al, 2019a), and more educated adults tend to have more educated children – regardless of migration.

To test whether there is a causal relationship between internal migration and children’s educational outcomes, we use information from the Egyptian Census on migration rates in the parents’ birthplace, which measures the networks that facilitate migration (as an instrumental variable). We find that the effect of parental migration is substantial and significant, reducing school dropout and increasing completed education.

Economic opportunities in urban locations may play a particularly important role in improving children’s educational outcomes. When we test whether physical school access – in terms of distance to schools – or economic factors – namely income and wealth – mediated the effect of rural to urban migration, we find that distance did not matter (Krafft et al, 2019a). Physical access to schools is nearly equitable in urban and rural areas, with just slightly longer travel times (zero to one minute longer for primary and preparatory, five minutes longer for secondary, on average (Krafft et al, 2019b).

Higher incomes and higher wealth for rural to urban migrant families do, however, explain a substantial part of the effect of rural to urban migration on education (Krafft et al, 2019a). When parents migrate, they access better economic opportunities, which allows them to support and sustain their children in school for longer.

Children in Egypt have the right to enrol in local schools regardless of their family’s migration status. Unlike other contexts, such as China, that restrict access to education for internal migrant children (UNESCO, 2018), Egypt requires only an identification card to enrol in school (Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, 2019).

The impacts of internal migration on children’s education are likely to be context-specific. But the results of our research in Egypt suggest that giving children the right to enrol regardless of family’s migration status can lead to equitable educational outcomes.

Further reading

Bernard, A, M Bell and J Cooper (2019) ‘Internal Migration and Education: A Cross-National Comparison’, paper commissioned for the Arab States 2019 Global Education Monitoring Report, Migration, Displacement and Education: Building Bridges, Not Walls.

David, A, N El-Mallakh and J Wahba (2019) ‘Internal versus International Migration in Egypt: Together or Far Apart’, ERF Working Paper No. 1366.

Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (2019) ‘Responses to Information Requests. Country of Origin Information’, retrieved 23 May 2019 from https://www.irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/country-information/rir/Pages/index.aspx?doc=456540&pls=1

Krafft, C, A Cortes Mendosa and S Thao (2019a) ‘Internal Migration and Education: Findings from Egypt’, paper commissioned for the Arab States 2019 Global Education Monitoring Report: Migration, Displacement and Education: Building Bridges, Not Walls.

Krafft, C, C Keo and L Fedi (2019b) ‘Rural Women in Egypt: Opportunities and Vulnerabilities’, ERF Working Paper No. 1359.

Sieverding, M, R Roushdy, R Hassan and A Ali (2019) ‘Perceptions of Service Access in A Context of Marginalization: The Case of Young People in Informal Greater Cairo’, ERF Working Paper No. 1289.

UNESCO (2019) Arab States Global Education Monitoring Report: Migration, Displacement and Education: Building Bridges, Not Walls.

Wahba, J (2007) ‘An Overview of Internal and International Migration in Egypt’, ERF Working Paper No. 703.

Zohry, GA (2002) ‘Rural-to-Urban Labor Migration: A Study of Upper Egyptian Laborers in Cairo’, Sussex at Brighton.