In a nutshell

Demographic pressures on Egypt’s labour supply have decreased.

The ‘youth bulge’ generation are young adults now, their labour market entry complete, while the ‘echo’ of the youth bulge is school-aged.

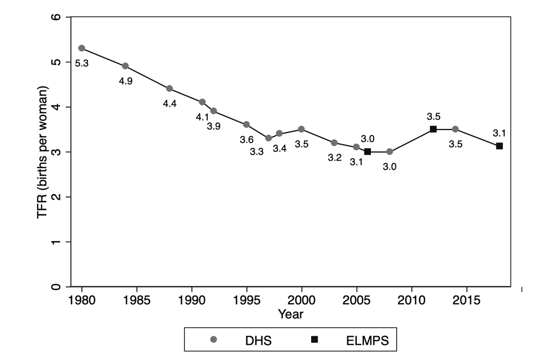

Fertility, which had declined in Egypt and then risen, has once again fallen. The total fertility rate (births per woman), which was 3.5 in 2012-2014, fell to 3.1 in 2018.

Egypt’s potential labour supply depends, first and foremost, on demographics – the growth and changing composition of its working-age population.

Historically, Egypt had experienced a large ‘youth bulge’, which placed substantial pressures on the labour market (Amer, 2009, 2015; Assaad and Krafft, 2015). By 2012, the cohorts of the youth bulge were largely young adults, beginning to form families of their own, creating a demographic ‘echo’. This echo was compounded by an increase in fertility (Krafft and Assaad, 2014).

New data from 2018 demonstrates that demographic pressures are easing; labour market entrants are fewer, due to the demographic ‘trough’ being at the age of entry to the labour market. Moreover, after rising, fertility has fallen back to lower levels (Krafft et al, 2019). But the echo generation is placing substantial pressures on the education system and will soon create new labour supply pressures.

The youth bulge has become older, but the echo has grown

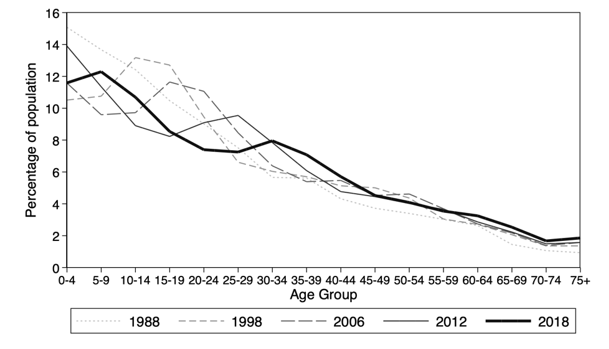

Since 1988, a key characteristic of Egypt’s changing demographics has been the development of a youth bulge, a disproportionate share of young people in the population (Figure 1). Egypt’s youth bulge occurred when mortality fell but there was a lag before fertility decreased (Assaad and Roudi-Fahimi, 2007; Miller and Hirschhorn, 1995; Rashad, 1989; Robinson and El-Zanaty, 2006).

In 1988, the youth bulge generation were children. By 1998, the peak of the youth bulge was aged 10-19 and began placing substantial pressure on the labour market. In 2006, the peak was aged 15-24, further pressuring the labour market. Yet by 2012, demographic pressures on the labour market began to abate, as the peak of the youth bulge was 25-29 and had largely entered the labour market. In 2018, the peak of the youth bulge was aged 30-34, and left a trough of reduced labour supply pressures with a smaller population aged 20-29.

Figure 1: Egypt’s youth bulge has become older, but the echo has grown

Population structure of Egypt (percentage in five-year age group), by wave

Source: Krafft et al (2019) based on data from the Labor Force Survey (LFS) 1988 and the Egypt Labor Market Panel Survey (ELMPS) 1998-2018

As the children of the youth bulge generation reached adulthood, they began to have children of their own, creating an echo generation. In 2012, we can see the beginning of an echo generation, with a second peak in the population aged 0-4. The growth of the echo was compounded by rising fertility rates (Figure 2).

The Demographic and Health Surveys (DHSs) demonstrated a decrease in fertility over time, to a total fertility rate of 3.0 births per woman in 2008. Yet the 2012 Egypt Labor Market Panel Survey (ELMPS) and the 2014 DHS both indicated a rise in fertility to 3.5 births per woman. The new 2018 wave of the ELMPS provides important new evidence that fertility is once again declining, having fallen to 3.1 births per woman.

Figure 2. After a rise in fertility in 2012-2014, fertility fell by 2018

Total fertility rate (births per woman) over time

Source: Krafft et al (2019) based on data from DHSs and ELMPS 2006-2018

Why has fertility resumed its decline? After a period of rising ages at marriage, women had, more recently, been marrying at somewhat earlier ages, especially from ages 20-28. This shift may have contributed to rising fertility rates. There are some signs of this trend now stabilising (Krafft et al, 2019).

Fertility declines between 2012 and 2018 were concentrated at older ages (25 and up). Contraceptive prevalence rates increased. Among currently married women aged 15-49, 62.6% were taking steps to prevent pregnancy in ELMPS 2018 (Krafft et al, 2019), compared with only 58.5% in the DHS 2014 (Ministry of Health and Population, El-Zanaty and Associates, and ICF International, 2015).

Whether this demographic trend of falling fertility continues, stalls and stabilises, or reverses again will have enormous implications for the health and education systems in the near term and the labour market in the long term. The echo generation was aged 5-9 in 2018, placing intense pressures on the education system. By the end of the 2020s, these same children will reach working age, bringing another wave of labour supply pressures.

Egypt must take advantage of the window of reduced demographic pressures. The youth bulge has grown up and the echo is still school-aged. This provides an important window of opportunity with reduced demographic pressures to try to address long-standing structural labour market challenges.

Further reading

Amer, Mona (2009) ‘The Egyptian Youth Labor Market School-to-Work Transition, 1988-2006’, in The Egyptian Labor Market Revisited edited by Ragui Assaad, The American University in Cairo Press.

Amer, Mona (2015) ‘Patterns of Labor Market Insertion in Egypt, 1998-2012’, in The Egyptian Labor Market in an Era of Revolution edited by Ragui Assaad and Caroline Krafft, Oxford University Press.

Assaad, Ragui, and Caroline Krafft (2015) ‘The Evolution of Labor Supply and Unemployment in The Egyptian Economy: 1988-2012’, in The Egyptian Labor Market in an Era of Revolution edited by Ragui Assaad and Caroline Krafft, Oxford University Press.

Assaad, Ragui, and Farzaneh Roudi-Fahimi (2007) ‘Youth in the Middle East and North Africa: Demographic Opportunity or Challenge?’, Population Reference Bureau Policy Brief, Washington, DC.

Krafft, Caroline, and Ragui Assaad (2014) ‘Beware of the Echo: The Impending Return of Demographic Pressures in Egypt’, ERF Policy Perspective No. 12.

Krafft, Caroline, Ragui Assaad and Caitlyn Keo (2019) ‘The Evolution of Labor Supply in Egypt from 1988-2018: A Gendered Analysis’, ERF Working Paper (forthcoming).

Miller, Peter, and Norbert Hirschhorn (1995) ‘The Effect of a National Control of Diarrheal Diseases Program on Mortality: The Case of Egypt’, Social Science & Medicine 40(10): S1-30.

Ministry of Health and Population, El-Zanaty and Associates, and ICF International (2015) ‘Egypt Demographic and Health Survey’, Cairo: Ministry of Health and Population and ICF International.

Rashad, Hoda (1989) ‘Oral Rehydration Therapy and Its Effect on Child Mortality in Egypt’, Journal of Biosocial Science 21(S10): 105-113.

Robinson, Warren, and Fatma El-Zanaty (2006) The Demographic Revolution in Modern Egypt, Lexington Books.