In a nutshell

The EU’s decision to relax origin requirements for certain goods produced in Jordan for a 10-year period might help to address the Syrian refugee crisis by boosting Jordanian exports to Europe.

Products with relaxed requirements include petroleum products, fertilisers, some chemical and plastic products, articles of leather, textiles and apparel.

Manufacture from fabric is sufficient to confer origin on Jordanian apparel, which amounts to a temporary replacement of the double transformation rule by a single transformation rule.

The crisis in Syria has resulted in Jordan hosting about 1.47 million refugees, equivalent to nearly 20% of the nation’s population. One of the responses from the European Union (EU) has been to improve market access for Jordanian exports, including a qualified simplification of ‘rules of origin’ (RoO) requirements. This was announced in August 2016 and became effective in 2017 for a period of 10 years for activities in qualifying zones.

Our recent study (Brunelin et al, 2018) compares Jordan’s current utilisation of EU preferences under the EU-Jordan free trade agreement (EUJFTA) with its use of US preferences under the Jordan-US FTA (JUSFTA). The results indicate that this initiative might help to address the Syrian refugee crisis by boosting Jordanian exports to the EU.

The study focuses on apparel exports, a labour-intensive sector that faced different RoO requirements between the two FTAs prior to the recent EU decision. From a broader perspective, simplification of RoO requirements may be the easiest way to restore preferential market access, especially for the EU and the United States, which have extended preferences to many trading partners.

Exports have grown faster under JUSFTA than under EUJFTA…

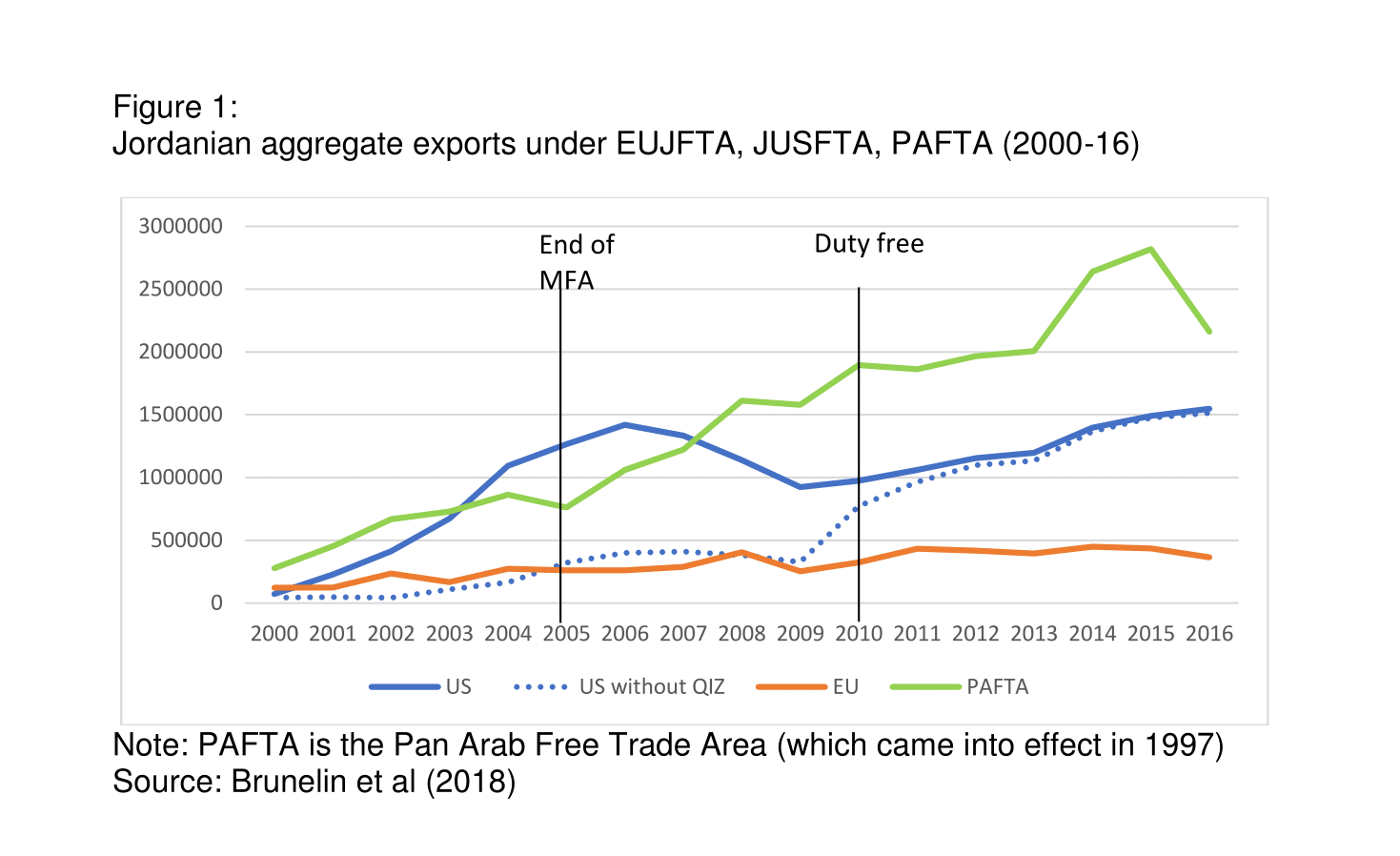

When exports to the United States include those from the ‘qualified industrial zones’ (QIZs), they show a sharp increase from 2001, the first year of JUSFTA implementation. This is because exports of apparel from the QIZs – which have very similar RoO requirements to those under JUSFTA – could enter the US market duty-free from the start while exports of apparel from Jordan as a whole could only enter duty-free starting in 2010.

If exports to the United States are excluded from the QIZs, Figure 1 shows that the growth rate of exports is the same for EUJFTA and JUSFTA until 2009. Then, exports from QIZs contract until virtually disappearing by 2014. Thus, over a similar period of preferential trade, Jordanian exports to the United States have grown faster than Jordanian exports to the EU.

… despite similar (and low) preferential margins…

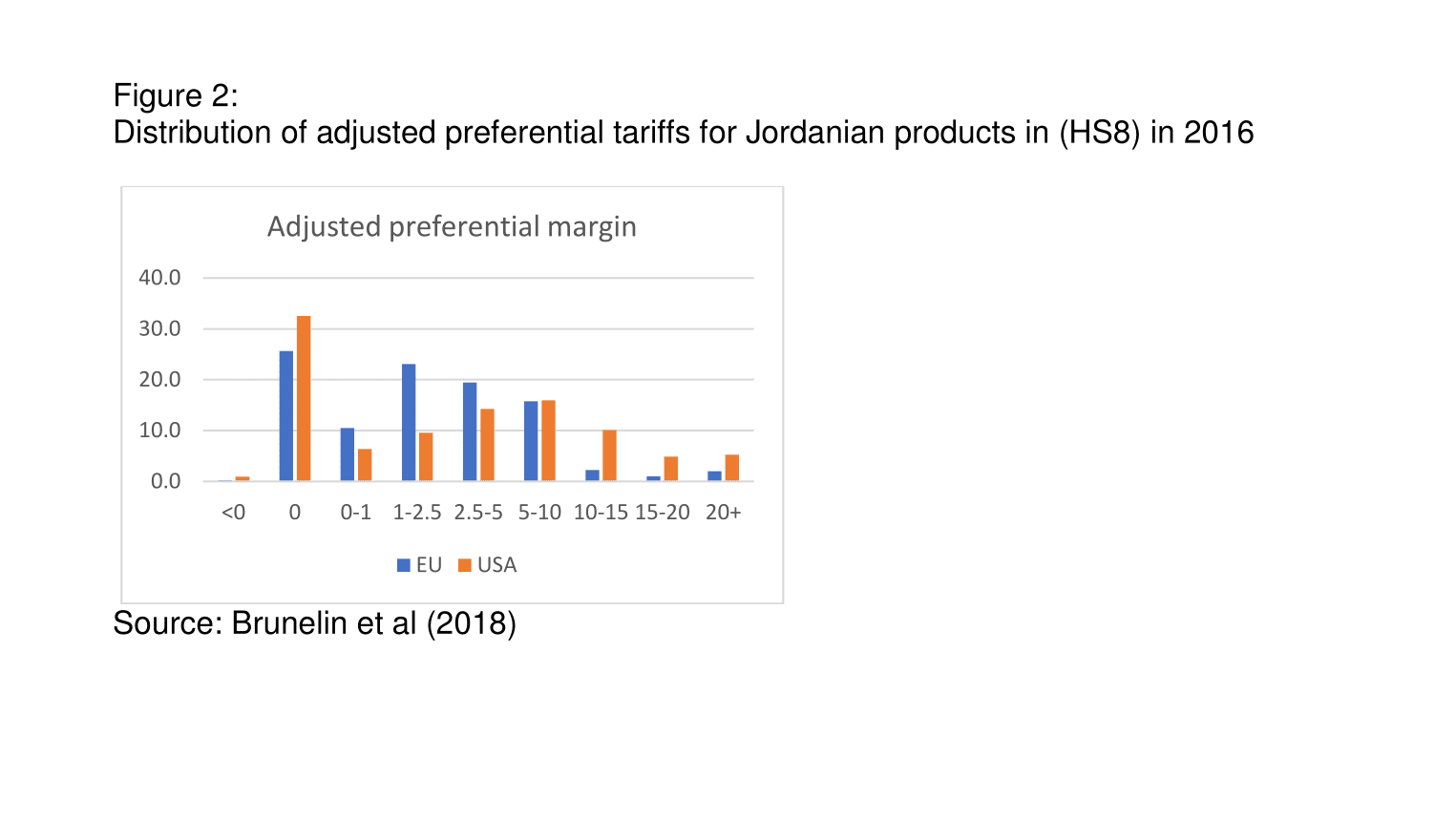

Adjusted preferential margins provide a first rough measure of potential market access because they exclude from preferences the trade-weighted preferences extended to other partners. These adjusted margins are shown in Figure 2 at the most disaggregated (HS8) product level (the difference between unadjusted and adjusted margins are reported for apparel in Table 1).

Figure 2 shows a similar distribution of preferences for both countries. Around 25-30% of Jordanian exports to the EU and the United States have no preferential margin, a reflection of zero ‘most favoured nation’ tariffs.

Both the EU and the United States only have 15% of their margins for Jordanian imports in the 5-10% range. The EU has a lower share of tariff lines with preferential margins in the 10-15% range and beyond (around 2%-3% compared with 5% for the United States). All in all, both the EU and the United States still have non-negligible access to offer to Jordan.

Origin requirements to qualify for preferential access in apparel are stringent under EUJFTA…

Effective market access must take account of the costs of complying with RoO requirements and other compliance procedures (such as certification methods). RoO requirements ensure that products involve a certain level of production within the Contracting Party to qualify for preferential treatment, thereby excluding goods produced elsewhere but simply shipped via the Contracting Party to benefit from preferential access.

A high ‘preference utilisation rate’ (PUR) is the first yardstick for assessing the intended effects of any FTA. Three factors are important in accounting for differences in utilisation rates across sectors and eligible countries:

- The depth of effective preferential access captured by the unadjusted and the adjusted preferential margins.

- The complexity of the RoO requirements.

- The size of the shipment because of the fixed costs of complying with the RoO requirements.

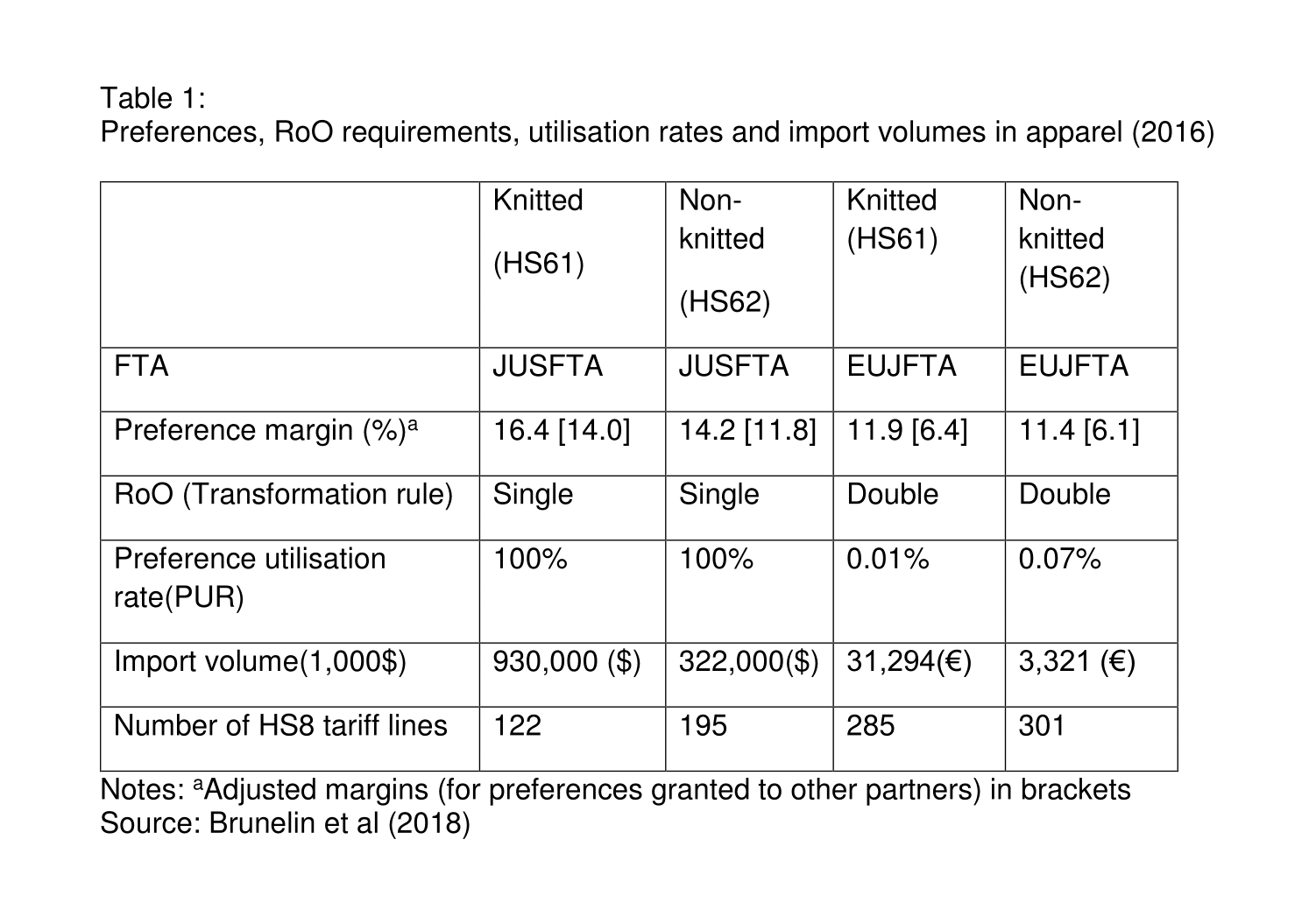

Table 1 summarises the importance of these inter-related factors for PURs in apparel imports under JUSFTA and EUJFTA. Preferences are higher under JUSFTA, especially when effective preferential access is measured correctly by the adjusted margin (a comparison of the unadjusted and adjusted margins shows that the EU extends preferences to a greater number of partners than the United States).

But adjusted preferences under EUJFTA are still over 5%, which is relatively high, since the worldwide trade-weighted preference margin is barely over 1% (Carpenter and Lendle, 2011). Excluding intra-European trade, WTO (2011) estimates that, for the 20 largest importers accounting for 90% of world trade, only 16% of their imports from partners qualify as preferential trade (on the assumption that all preferences are fully utilised).

For apparel, different RoO requirements are the most important difference between the two FTAs. In the case of JUSFTA, satisfying origin requires minimum domestic content – the ‘single transformation rule’ (textilesapparel – see Table 1)). Under EUJFTA prior to the decision of August 2016, Jordan’s requirement for access required a ‘double transformation rule’ (yarntextilesapparel – see Table 1).

… have contributed to low preference utilisation rates in apparel under EUJFTA

Table 1 reports the sharp differences in PURs between EUJFTA and JUSFTA. The upshot is that for the market for imports of apparel (which is of comparable size in the EU and the United States), those under EUJFTA are negligible while they are from 100 to 300 times larger under JUSFTA.

This pattern does not extend to other products at the HS8 level where PURs are relatively similar for broad ranges of preferential margins. As expected, PURs are higher for products with higher adjusted preferential margins and, for given preference margins, higher PURs are observed for products with larger traded volumes, an indication of the presence of fixed costs associated with satisfying RoO requirements (Keck and Lendle, 2012).

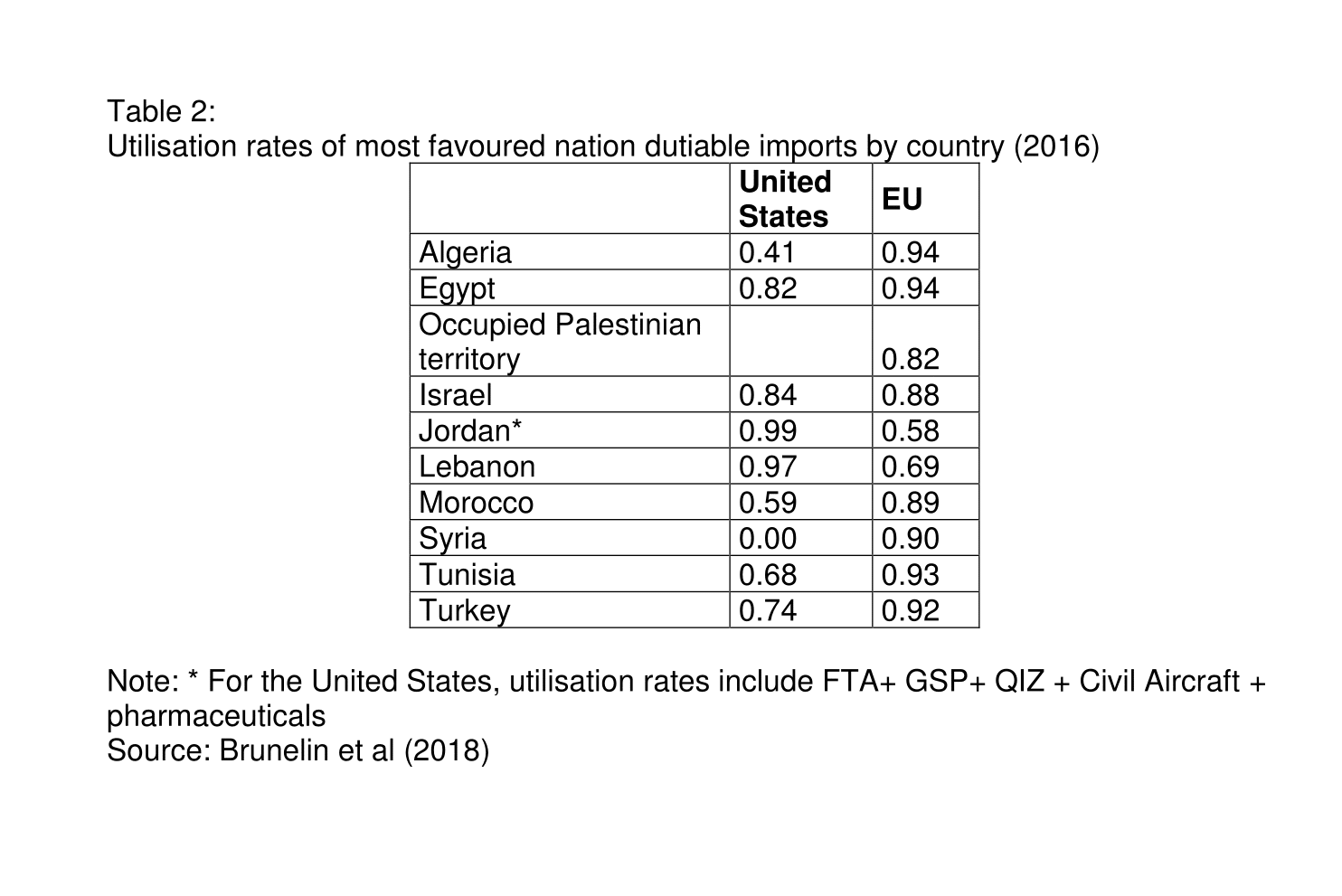

Further support is given in Table 2, which compares the aggregate PURs for EU and US FTAs with some MENA countries and, in some cases, for non-reciprocal preferences under the ‘generalised system of preferences’ (GSP) for the United States. Recall that, for each partner, unadjusted preferential margins are usually the same across FTA partners, so a comparison of PURs is a rough indication of the effects of RoO requirements.

For EU FTAs, if the Occupied Palestinian territory utilisation is omitted, PURs are high except for Jordan (and to a lesser extent Lebanon). Since RoO requirements are the same for all EU partners, differences in PURs could reflect composition effects and/or fixed costs playing out differently across shipment sizes.

By contrast, in the United States, RoO requirements vary across partners and for Jordan for apparel, they are most lenient compared with the other partners in Table 2. Among the US FTAs, utilisation rates are highest for Egypt, Jordan and Lebanon, which all have the single transformation rule for apparel.

It is noticeable that Morocco has a low PUR in the United States despite the same preferential margin as Jordan. Although it does not have an FTA with the United States, Tunisia has GSP with higher PURs than Morocco. This difference in utilisation rates is most likely due to Morocco facing much stricter RoO requirement for apparel.

The relaxation decision should temporarily alleviate the refugee crisis

The EU’s decision relaxed origin requirements for certain goods produced in Jordan for a 10-year period up till 31 December 2026. Products with relaxed RoO requirements include petroleum products, fertilisers, some chemical and plastic products, articles of leather, textiles and apparel. Notably, manufacture from fabric is sufficient to confer origin on Jordanian apparel.

This amounts to a temporary replacement of the double transformation rule by a single transformation rule for apparel. The decision only applies to goods produced in development zones and industrial areas listed in the decision. In those qualifying zones, the total work force of each production facility should contain at least 15% refugees in the workforce during the first and second years and at least 25% from the third year on.

The decision states that the aim is to create 200,000 job opportunities for Syrian refugees. This may be an ambitious target:

- First, since beneficiaries must be located in designated special economic zones, this could be equivalent to a quota on exports eligible for preferential market access.

- Second, companies operating outside the designated areas will have to incur costs to move operations if they want to benefit from preferences.

- Third, less developed countries have had access to the EU market under the single transformation rule since 2011.

- Fourth, as noted in our study and elsewhere (Cadot and Melo, 2007; Mavroidis and Vermulst, 2018), further simplifications in RoO requirements are to be expected in coming years.

Further reading

Brunelin, Stéphanie, Jaime de Melo and Alberto Portugal-Perez (2018) ‘Improving Market Access for Developing Countries: A Case Study of Jordan’s Exports to the EU’, FERDI Working Paper No. 211.

Cadot, Olivier, and Jaime de Melo (2007) ‘Why OECD Countries Should Reform their Rules of Origin’, World Bank Research Observer 23(1): 77-105.

Carpenter, Theresa, and Andreas Lendle (2011) ‘How Preferential is World Trade?’, Vox.

Keck, Alexander, and Andreas Lendle (2012) ‘New Evidence on Preference Utilization’, ERSD-2012-12.

Mavroidis, Petros, and Edwin Vermulst (2018) ‘The Case for Dropping Preferential Rules of Origin’, Journal of World Trade 52(1): 1-14

WTO (2011) World Trade Report: The WTO and Preferential Trade Agreements: From Co-existence to Coherence, World Trade Organization.