In a nutshell

Fertility rates in Egypt have dropped substantially: from 3.5 births per woman in 2014 to 2.2 in 2023, reducing demographic pressures on the labour market in the long term.

Unemployment has decreased, but this is driven primarily by falling labour force participation rather than improved job prospects. Rates of labour force participation continue to decline, particularly among younger men and educated women.

The echo generation of the youth bulge will enter the labour market within the next decade, creating new labour market pressures and challenges for policy-makers.

Egypt stands at a critical juncture in its demographic trajectory. After a period of demographic pressure due to the ‘youth bulge’, the labour market is experiencing temporary relief, as the peak of the youth bulge is now aged 35-39. But the sizable ‘echo’ generation – the children of the youth bulge, with a peak at ages 5-14 – will reach working age within the next decade, leading to a surge in labour market entrants (see Figure 1).

But one of the most striking trends in Egypt over the past decade has been the recent sharp decline in fertility rates; the total fertility rate dropped from 3.5 births per woman in 2014 to 2.2 in 2023. The decline in fertility is also visible in the much smaller group of children aged 0-4 in 2023 than previous years (see Figure 1). Fewer births in recent years mean less pressure on the health system, a smaller cohort entering the education system in the short run and, eventually, the labour market in the long run.

Figure 1: The population structure of Egypt (percentage in five-year age group), 1988-2023

The youth bulge is now prime age (35-39 in 2023) while the echo generation (the peak aged 5-14) is about to enter and put pressure on the labour market.

Labour force participation: a steady decline

Labour force participation in Egypt has declined since 2012, with participation rates falling from 51% in 2012 to 45% in 2023. Both men and women’s participation have declined over time, from 80% in 2012 for men to 72% in 2023.

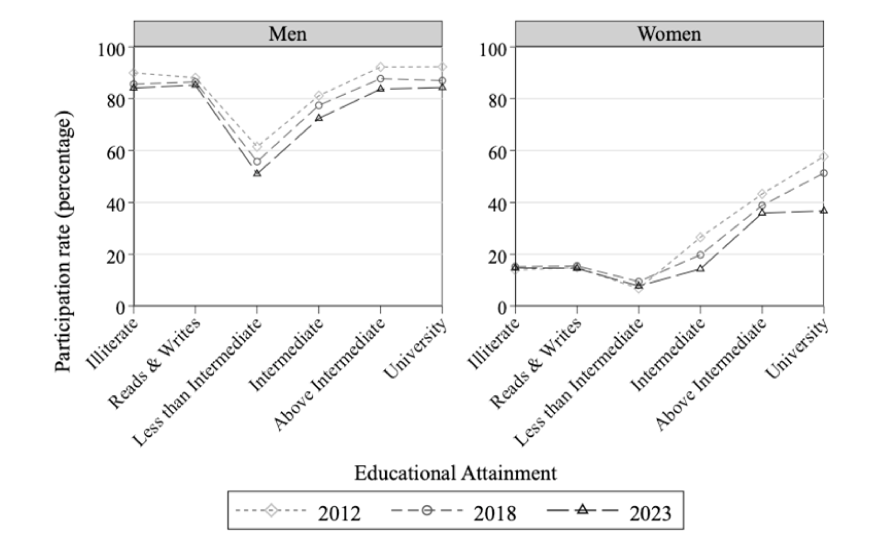

The drop in participation is particularly acute among younger men, who are increasingly staying out of the labour market longer even after completing their education. For women, participation rates were already low at 23% in 2012, but they have fallen further in 2023 to 18%. The drop has been especially sharp for educated women (see Figure 2) who are increasingly withdrawing due to shrinking public sector opportunities (Assaad, Hendy et al, 2020).

Figure 2: Labour force participation rates (percentage) by sex and education level, ages 15-64, 2012-23

Men have had declining participation across education levels, while there has been a sharp decline in participation among university-educated women.

Unemployment trends and future labour market challenges

Unemployment in Egypt has historically been influenced more by structural factors than by cyclical conditions, with a central role played by the influx of educated labour market entrants (Assaad, 2019; Assaad and Krafft, 2023; Krafft and Assaad, 2014). Between 2012 and 2023, unemployment rates (standard, search required definition, as a share of the labour force) declined from 8.7% to 6.3%, despite a simultaneous fall in employment (from 47% to 42% as a share of the working age population).

The unemployment decline is thus due primarily to reduced labour market participation and a temporary reduction in demographic pressures, rather than improvements in job creation. The echo generation, who are set to enter the labour market in the coming decade, may reverse this trend. Gender disparities remain, with the unemployment rate for women much higher than for men (12.8% for women versus 4.8% for men in 2023), though the gap has narrowed over time as more women opt not to enter the labour force altogether.

Education and youth joblessness

Despite impressive gains in educational attainment, Egypt’s educated workforce is facing appreciable challenges in securing employment. Youth, in particular, are struggling to make the transition from school to work (Amer and Atallah, 2022; Assaad et al, 2023), with a sizeable proportion classified as ‘not in education, employment or training’ (NEET).

The share of young people aged 15-29 who are NEET, along with the share who are jobless (not in employment or training, among those not in school) show concerning trends. While the NEET rate fell from 40% in 2012 to 35% in 2018, it did so primarily because women were remaining in school longer. The NEET rate rose for men, from 14% in 2012 to 19% in 2023. Joblessness increased after 2012 for men and women, rising from 20% in 2012 for men to 33% in 2023, and from 86% to 89% for women.

These trends indicate that addressing education alone may be insufficient to resolve the persistent issue of difficult-school-to-work transitions. Policy interventions targeting job creation and labour market integration are crucial to reducing NEET and joblessness.

Policy recommendations

To address Egypt’s labour market challenges, the findings from the ELMPS 2023 suggest the need for targeted and meaningful interventions.

Job creation in high-demand sectors

The focus must be on creating quality jobs, particularly in sectors that can absorb large numbers of young and educated workers as the echo generation enters the labour market. Green jobs show high growth potential (Assaad and Krafft, 2024), as does the information and communication technology sector (ICT), with the latter being particularly promising for women’s employment (Selwaness et al, 2023; Yasser et al, 2024).

Ensuring a competitive private sector will be an important part of facilitating robust job creation (Assaad, Krafft et al, 2020; Chekir and Diwan, 2015).

Reinvigorating women’s labour market participation

Policies should support women who have been increasingly discouraged by creating an enabling environment for women to participate in the workforce. This includes recognising, reducing and redistributing care work (Atallah and Hesham, 2024; ERF and UN Women, 2020; Krafft and Li, 2024), promoting flexible work arrangements (Ho et al, 2024; Jalota and Ho, 2024) and addressing social norms that discourage women’s labour market participation (Keo et al, 2022; National Council for Women et al, 2023).

Interventions may need to be multi-faceted to tackle the many constraints women face; for example, child care or child care alone may not be sufficient to increase women’s participation without addressing restrictive gender norms (Caria et al, 2022; Krafft and Li, 2024).

Improving labour market institutions

Strengthening labour market institutions is key to ensuring the efficient matching of job-seekers with available employment. But programmes that simply match the unemployed with existing jobs are unlikely to be effective, as existing jobs tend not to meet the expectations of the unemployed (Caria et al, 2022; Groh et al, 2015).

More promising interventions include better signalling between education systems and the labour market (Assaad et al, 2018), for example, improving labour market information systems (Angel-Urdinola et al, 2013; El-Kogali and Krafft, 2020).

Further reading

Amer, M, and M Atallah (2022) ‘The School to Work Transition and Youth Economic Vulnerability in Egypt’, The Egyptian Labor Market: A Focus on Gender and Vulnerability edited by C Krafft and R Assaad, Oxford University Press.

Angel-Urdinola, DF, A Kuddo, A Semlali, S Belghazi, A Hilger, R Leon-Solano, M Wazzan and D Zovighian (2013) Building Effective Employment Programs for Unemployed Youth in the Middle East and North Africa, World Bank.

Assaad, R (2019) Moving beyond the unemployment rate: Alternative measures of labour market outcomes to advance the decent work agenda in North Africa, International Labour Organization and ERF.

Assaad, R (2022) ‘Beware of the echo: The evolution of Egypt’s population and labor force from 2000 to 2050’, Middle East Development Journal 14(1): 1-31.

Assaad, R, R Hendy, M Lassassi and S Yassin (2020) ‘Explaining the MENA Paradox: Rising Educational Attainment, Yet Stagnant Female Labor Force Participation’, Demographic Research 43(28): 817-50.

Assaad, R, and C Krafft (2023) ‘Labour market dynamics and youth unemployment in the Middle East and North Africa: Evidence from Egypt, Jordan, and Tunisia’, LABOUR 37(4): 519-53.

Assaad, R, and C Krafft (2024) ‘Identifying and describing green occupations in Egypt: A first step in formulating effective education and employment policies to support the green transition’, ERF Policy Research Report (forthcoming).

Assaad, R, C Krafft and D Salehi-Isfahani (2018) ‘Does the type of higher education affect labor market outcomes? Evidence from Egypt and Jordan’, Higher Education 75(6): 945-95.

Assaad, R, C Krafft and C Salemi (2023) ‘Socioeconomic Status and the Changing Nature of School-to-Work Transitions in Egypt, Jordan, and Tunisia’, ILR Review 76(4): 697-723.

Assaad, R, C Krafft and S Yassin (2020) ‘Job creation or labor absorption? An analysis of private sector job growth in Egypt’, Middle East Development Journal 12(2): 177-207.

Atallah, M, and M Hesham (2024) ‘Unpaid Care Work in Egypt: Gender Gaps in Time Use’, ERF Working Paper (forthcoming).

Caria, S, B Crepon, H ElBehairy, N Fadlalmawla, C Krafft, A Nagy, L Mottaghi, N Zeitoun and S El Assiouty (2022) Child Care Subsidies, Employment Services and Women’s Labor Market Outcomes in Egypt: First Midline Results.

Chekir, H, and I Diwan (2015) ‘Crony Capitalism in Egypt’, Journal of Globalisation and Development 5(2): 177-211.

ERF and UN Women (2020) Progress of Women in the Arab States 2020: The role of the care economy in promoting gender equality, UN Women.

El-Kogali, SET, and C Krafft (eds) (2020) Expectations and Aspirations: A New Framework for Education in the Middle East and North Africa, World Bank.

Groh, M, D McKenzie, N Shammout and T Vishwanath (2015) ‘Testing the importance of search frictions and matching through a randomized experiment in Jordan’, IZA Journal of Labor Economics 4(7): 1-20.

Ho, L, S Jalota and A Karandikar (2024) ‘Bringing Work Home: Flexible Arrangements as Gateway Jobs for Women in West Bengal’, STEG Working Paper.

Jalota, S, and L Ho (2024) ‘What Works for Her? How Jobs from Home and Local Offices Affect Female Labor Force Participation in Urban India’, mimeo.

Keo, C, C Krafft and L Fedi (2022) ‘Rural Women in Egypt: Opportunities and Vulnerabilities’, in The Egyptian Labor Market: A Focus on Gender and Vulnerability edited by C Krafft and R Assaad, Oxford University Press.

Krafft, C, and R Assaad (2014) ‘Why the Unemployment Rate is a Misleading Indicator of Labor Market Health in Egypt’, ERF Policy Perspective No. 14.

Krafft, C, R Assaad and Z McKillip (2024) ‘The Evolution of Labor Supply in Egypt through 2023’, ERF Working Paper No. 1749.

Krafft, C, and R Li (2024) ‘The impact of early childhood care and education on maternal time use in Egypt’, ERF Working Paper No. 1751.

National Council for Women, Baseera, and World Bank (2023) Social Norms and Female Labor Force Participation in Egypt.

Selwaness, I, R Assaad and M El Sayed (2023) ‘The Promise of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Jobs in Egypt’, ERF Policy Research Report SPRR 2023-3.

Yasser, R, I Selwaness and C Poggi (2024) ‘The Use of Information and Communication Technology in the workplace in Egypt’, ERF Working Paper (forthcoming).

This column summarises the ERF policy brief ‘The Evolution of Labor Supply in Egypt: Current and Future Challenges’. We acknowledge the financial support of the International Labour Organization through the government of the Netherlands and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, the World Bank Poverty and Equity Global Practice supported by the UK-funded Strategic Partnership for Egypt’s Inclusive Growth Trust Fund (SPEIG TF), and the World Bank MENA Chief Economist’s office, the Agence Française de Développement, the Ministry of Planning, Economic Development and International Cooperation, Egypt, and UNICEF for the Egypt Labor Market Panel Survey 2023, on which this research is based. We appreciate the comments of discussant Dr Magued Osman in the ‘Egypt Labor Market Panel Survey First Drafts Discussion Workshop’, and the research support of Joy Moua.