In a nutshell

The sanctions on Iran are expected to cause a significant increase in the country’s emissions of carbon dioxide by 2028, ranging from 12.5% to 30% compared with the baseline scenario; the extent of the rise depends on various factors, including energy intensity and economic growth.

Prolonging sanctions could significantly hinder improvements in Iran’s energy intensity, use of clean technologies and reduction of carbon emissions.

The growing use of sanctions for political goals could be costly for the global environment; policy-makers should assess carefully the duration and intensity of sanctions, promoting more effective and environmentally responsible methods to achieve diplomatic objectives.

Extensive research has documented the economic consequences of sanctions on Iran (see Farzanegan and Batmanghelidj, 2023, for a recent survey). But the environmental impacts, which could exacerbate social conflicts (Farzanegan and Gholipour, 2023), have received relatively little attention in empirical work.

Existing studies examining the effects of sanctions on environmental indicators in Iran typically employ descriptive or time series analysis methods (for example, Fotourehchi, 2020; Madani, 2021; Hakim and Makuch, 2022). While these studies offer valuable insights, they do not incorporate causal loop diagrams, feedback mechanisms or dynamic interactions among variables across various policy scenarios.

Sanctions can have a significant impact on the environment, particularly by restricting imports of clean technologies and reducing energy efficiency (Jabari et al, 2024). This can lead to increased pollution and potential breaches of international environmental obligations, which mandate financial, technical and scientific support to sanctioned countries.

Assessing the environmental effects of sanctions is a complex endeavour, involving multiple variables interacting within dynamic frameworks that include various causal loop diagrams and feedback structures.

Our new study (Balali et al, 2024) investigates the environmental impacts of international sanctions by focusing on energy-related carbon emissions using system dynamics modelling.

System dynamics has become increasingly popular as a method for understanding policy issues and guiding decision-making across diverse fields such as health, sustainability and defence (Malbon and Parkhurst, 2023). Our research aims to augment existing time series-based findings by exploring and constructing scenarios related to sanctions. These insights can offer policy-makers a more nuanced perspective on the potential impacts of different sanction scenarios on environmental performance.

The model developed in this study identifies economic growth and energy intensity as pivotal factors influencing energy consumption and carbon emissions. Our initial hypothesis suggests that while sanctions may lead to economic disruptions and a slowdown in growth, they might also contribute to an uptick in energy-related carbon emissions. This could be due to the expansion of the informal economy under sanctions (Farzanegan, 2013; Zamani et al, 2021). Economic activities in the informal economy increase emissions, which is then amplified by higher levels of public corruption (Biswas et al, 2012).

Scenarios development

To establish a meaningful analysis, it is essential to define a counterfactual trend or baseline scenario, which represents a situation without socio-technical constraints on carbon emissions and without imposed sanctions – referred to as ‘business as usual’. This scenario considers the current conditions of growth, energy consumption and carbon emissions without the influence of sanctions.

From the body of previous research, we identify two critical factors that have a significant impact on carbon emissions and the development of mitigation policies: growth and energy intensity. These factors are heavily influenced by international economic sanctions.

We then identify six scenarios based on different assumptions about sanctions and growth.

International economic sanctions are a primary factor affecting Iran’s growth and the variations in energy intensity across different sectors. The scenarios in this study are based on different periods of sanctions in Iran: before the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action or JCPOA (2008-15), during its implementation (2016-17) and after the reinstatement and intensification of sanctions (2018-20), alongside two patterns of energy intensity change.

Based on sensitivity analysis, model validation and current growth classifications, seven policy scenarios are identified within these three phases, as Table 1 shows. The first scenario examines the effect of sanctions in a context where energy intensity remains unaffected. These scenarios are calculated using real data from the World Bank (2021).

In Scenario 2, representing the pre-2016 sanctions period, the average annual growth rates in various sectors are as follows: agriculture at 3.43%, industry at 4.29% and services at 3.78%. Additionally, the average annual change in energy intensity across all sectors is 2.3%.

In contrast, Scenario 6, which corresponds to the post-2018 sanctions period, shows different average annual growth rates: agriculture at 4.12%, industry at 1.68% and services at -0.25%. The average annual change in energy intensity across all sectors is significantly higher at 7.96%.

Our study aims to capture the real impact of sanctions during the analysed periods and highlights the disparities between these two sanction periods.

Table 1. Definitions of different scenarios

Findings

The findings reveal that under the baseline scenario of business as usual, both fossil fuel energy consumption and carbon emissions are projected to increase steadily until 2028. Additionally, the temporary lifting of economic sanctions, as observed during the implementation of the JCPOA, could potentially reduce carbon emissions by approximately 5%.

But the reimposition of previous sanctions, highlighted by the JCPOA’s collapse in 2018 and the introduction of new sanctions, hampers growth and increases energy intensity across all sectors. This leads to higher energy consumption and carbon emissions, particularly when sanctions are in effect and energy intensity rises significantly (as demonstrated in Scenario 6 in Table 1).

Our findings suggest that the reintroduction of earlier sanctions is likely to cause a substantial increase in carbon emissions by 2028, ranging from 12.5% to 30% above the baseline scenario. The extent of this increase depends on various factors, including energy usage efficiency and different growth possibilities.

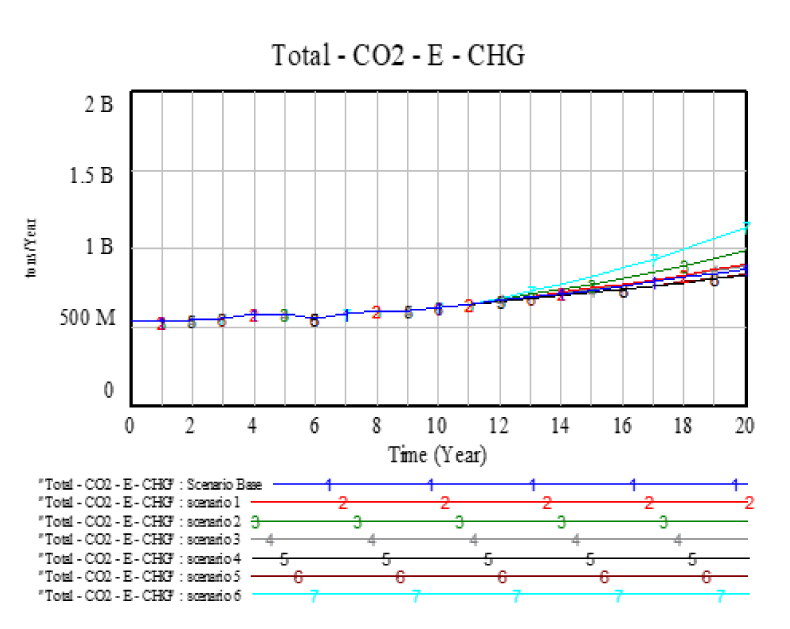

As Figure 1 shows, Scenario 6 (reflecting continuing economic sanctions) has the highest annual carbon emissions, reaching 1,135 million tons in 2028 due to worsening energy intensity. In contrast, Scenario 4, representing the JCPOA agreement with the highest growth rate, shows a reduction in carbon emissions.

Figure 1: Total annual carbon emissions in Iran under different scenarios

Conclusion

Sanctions costs extend beyond the sanctioned country, affecting the global community through negative externalities such as increased carbon emissions. The growing use of economic sanctions for political goals could become costly for the global environment. Policy-makers must carefully assess the duration and intensity of sanctions, promoting more effective and environmentally responsible methods to achieve diplomatic objectives.

Further reading

Balali, H, MR Farzanegan, O Zamani and M Baniasadi (2024) ‘Economic sanctions, energy consumption, and CO2 emissions in Iran: A system dynamics model’, Policy Studies 1-30.

Biswas, AK, MR Farzanegan and M Thum (2023) ‘Pollution, shadow economy, and corruption: Theory and evidence’, Ecological Economics 75: 114-25.

Farzanegan, MR (2013) ‘Effects of international financial and energy sanctions on Iran’s informal economy’, The SAIS Review of International Affairs 33(1): 13-36.

Farzanegan, MR, and E Batmanghelidj (2023) ‘Understanding economic sanctions on Iran: A survey’, The Economists’ Voice 20: 197-226.

Farzanegan, MR, and HF Gholipour (2023) ‘Does satisfaction with amenities and environment influence the taste for revolt in the Middle East?’, Constitutional Political Economy.

Fotourehchi, Z (2020) ‘Are UN and US economic sanctions a cause or cure for the environment: Empirical evidence from Iran’, Environment, Development and Sustainability 22: 5483-5501.

Hakim, S, and KE Makuch (2022) Conflicts of interest: The environmental costs of modern war and sanctions, Royal United Services Institute.

Jabari, L, A Salem, O Zamani and MR Farzanegan (2024) ‘Economic sanctions, energy efficiency, and environmental impacts: Evidence from Iranian industrial sub-sectors’, MAGKS Joint Discussion Paper Series in Economics No. 03-2024.

Madani, K (2021) ‘Have international sanctions impacted Iran’s environment?’, World 2: 231-52.

Malbon, E, and J Parkhurst (2023) ‘System dynamics modelling and the use of evidence to inform policymaking’, Policy Studies 44: 454-72.

Zamani, O, MR Farzanegan, J Loy and M Einian (2021) ‘The impacts of energy sanctions on the black-market premium: Evidence from Iran’, Economics Bulletin 41(2): 432-43.