In a nutshell

The effects of financial development and corruption on the shadow economy are contingent on the level of development in a country; indeed, these two factors play a significant role in nurturing informality in the middle- and low-income countries of the MENA region.

A set of policies targeting informality requires a multi-dimensional approach that considers the complex interactions between financial development, corruption and other factors such as trade openness and economic diversification.

By prioritising policies that promote formal economic engagement and transparency, MENA countries can effectively reduce the size of their informal economies and foster sustainable and inclusive economic growth.

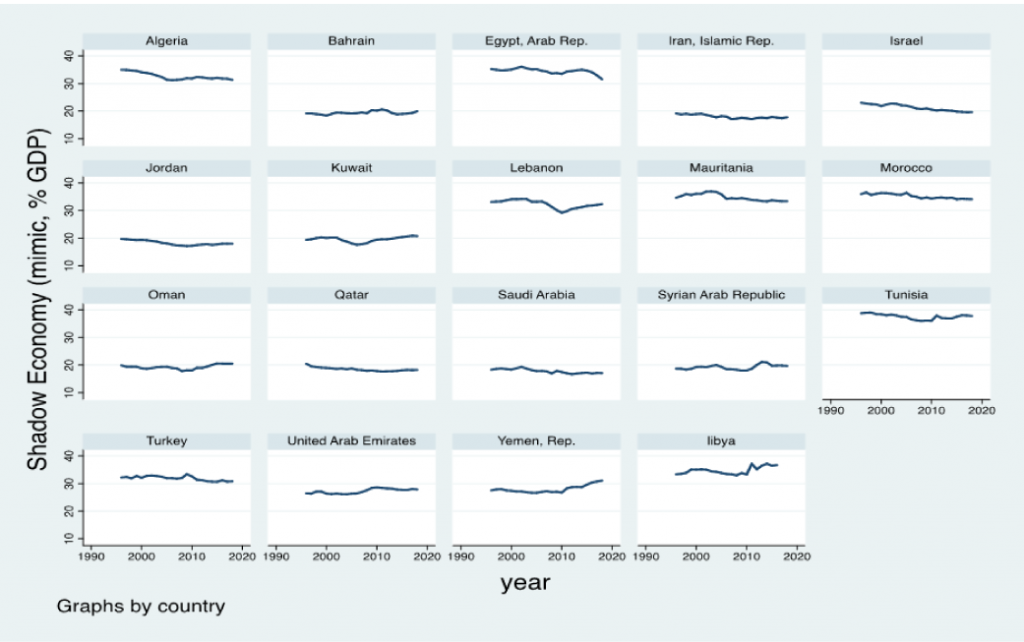

Informality is widely recognised as a key factor limiting growth in developing countries (La Porta and Shleifer, 2014). Estimates suggest that the share of the informal sector in the Middle East and North Africa over the last three decades has ranged between 20% and 40% of GDP (see Figure 1). Achieving a big shift of informal businesses into formality would help to release the region from the poverty and middle income traps, enhance inclusive growth, open further and wider opportunities for younger generations and boost tax revenues.

Figure 1. The size of informality as a percentage of GDP in MENA countries

Our study (Haffoudhi and Guizani, 2023) explores disparities in the extent of informality among MENA countries by examining how corruption and financial development influence the size of the shadow economy (also known as the informal economy, the underground economy or the unofficial economy).

Research on the relationship between corruption and the shadow economy has not as yet reached a consensus. While some authors argue that corruption and the shadow economy are complements, others suggest that the two are substitutes, notably in high-income countries.

Moreover, research on financial development and the shadow economy highlights a complex nexus between them. While a large body of this work reveals that the development of the banking sector is associated with a smaller size of the unofficial economy, some studies emphasise the potential existence of a non-linear relationship between them (Njangang et al, 2020).

More specifically, the effects of financial development on the shadow economy depend on several factors, such as the level of development and the size of remittances, as in the case of North African countries (Akçay and Karabulutoğlu, 2021). Additionally, many studies have confirmed that as the financial system in a country develops, the propensity to pay bribes fades away (Altunbas and Thornton, 2012; Jha, 2019).

Our study uses data on a sample of 21 countries in the MENA region over the period from 1996 to 2018 to investigate the nature of both the separate and interactive effects of the financial development and corruption on the size of the shadow economy. The innovation in our research is to explore the potential interplay between the development of the financial system and the corruption in shaping informality.

Our analysis reveals a number of insights. First, the econometric findings show that the development of the financial system in the region represents a significant incentive for firms to make the transition from informality to formality.

Second, corruption also provides incentives for entrepreneurs in the region to stay in the formal sector instead of going underground. By functioning as ‘grease for the wheels’ for businesses,smoothing the burden of complex regulation and inefficient public services, corruption inadvertently attracts more informal entrepreneurs to the official economy, For them, paying bribes becomes an opportunity to escape regulatory and judiciary punishment and, at the same time, to benefit from the advantages that the formal sector brings, notably in terms of access to bank funding.

Third, this effect of corruption on the unofficial economy depends on the levels of financial development. In fact, our econometric analysis shows positive and statistically significant coefficients of the interaction between financial development and corruption. This evidence demonstrates that these two variables are substitutes in reducing informal economic activities – that is, the marginal impact of increasing along one dimension is higher when the other dimension is low. Overall, we can assert that the efficiency of the financial sector in MENA economies reduces the corruption incentive (the grease for the wheels effect) for firms to seek to join and stay in the formal sector.

Fourth, the impacts of financial development and corruption on the shadow economy are contingent on the level of development in a country; indeed, these two factors play a significant role in nurturing informality in the group of middle- and low-income countries of the region. Clearly, informal activities in the high-income cohort of countries are derived from factors other than the level of financial development and corruption. For this category of countries, openness to international trade and the low level of diversification of their economies play more significant roles in fuelling underground activities.

Fifth, comparing low corruption countries to high corruption countries, we make the unexpected finding that financial development in the former is associated with larger sizes of the informal economy. This result underlines our theoretical analysis illustrating the ambiguity and complexity of the connection between the development of the financial system and the informal sector.

Sixth, the reducing effects of financial development and corruption on the size of the shadow economy are more important and remarkable in countries with relatively lower levels of financial development.

To conclude, a set of policies targeting informality requires a multi-dimensional approach that considers the complex interactions between financial development, corruption and other factors such as trade openness and economic diversification. Our study shows that to reduce unofficial economic activities to a manageable size, MENA countries need to promote financial sector development to provide incentives for formal economic ventures and implement anti-corruption measures to create a level playing field for businesses.

Additional key measures include unblocking economic potential, fostering transparency and accountability in governance, and enhancing openness to international trade to diversify the economy and mitigate informal practices. By prioritising policies that promote formal economic engagement and transparency, MENA countries can effectively reduce the size of their informal economies and foster sustainable and inclusive economic growth.

Further reading

Akçay, S, and E Karabulutoğlu (2021) ‘Do remittances moderate financial development-informality nexus in North Africa?’, African Development Review 33(1): 166-79.

Altunbas, Y, and J Thornton (2012) ‘Does financial development reduce corruption?’, Economics Letters 114: 221-23.

Haffoudhi, H, and B Guizani (2023) ‘Financial Development, Corruption and Shadow Economy: Evidence from MENA Countries’, ERF Working Paper No. 1687.

Jha, CK (2019) ‘Financial reforms and corruption: Evidence using GMM estimation’, International Review of Economics and Finance 62: 66-78.

La Porta, R, and A Shleifer (2014) ‘Informality and development’, Journal of Economic Perspectives 28(3): 109-26.

Njangang, H, LN Ndeffo and JP Ngameni (2020) ‘Does financial development reduce the size of the informal economy in sub‐Saharan African countries?’, African Development Review 32(3): 375-91.

Schneider, F, and A Buehn (2018) ‘Shadow economy: Estimation methods, problems, results and open questions’, Open Economics 1(1), 1-29.