In a nutshell

Flows of dirty and footloose products between countries decrease when regional trade agreements have environmental provisions that are legally enforceable and subject to dispute settlement; this especially holds for flows from non-OECD to OECD.

Most treaties and trade agreements with environmental provisions are more concentrated in advanced economies, confirming the ‘pollution haven hypothesis’ – the idea that developing countries are the repository for environmentally damaging production.

Deepening trade agreements to go beyond a simple reduction in tariffs is crucial for MENA; including environmental provisions in deeper trade agreements could make the region’s trade policy more in line with the ambitions of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Despite the fact that flows of international trade have contributed to deterioration of the global climate, trade policy has the potential to reduce carbon emissions through the environmental provisions that are included in regional trade agreements (RTAs). Indeed, over the last two decades, there has been an increase in the number of environmental provisions included in such agreements.

To date, these provisions have been more concentrated in agreements involving developed countries than those involving developing countries. Between 1956 and 2016, 295 RTAs were created and 93% of them included at least one environmental provision. Of that share, 143 were negotiated between developed economies, 108 between developed and developing economies, and 23 between developing economies.

Compared with other countries, those in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region tend to have fewer environmental provisions in the trade agreements of which they are signatories, with most of the provisions not legally enforceable. This indicates the extent to which most trade agreements involved MENA countries are rather shallow.

Research on environmental provisions and trade flows

In recent research, we distinguish between three types of products:

- Dirty-immobile products: those from pollution-intensive industries for which incurred pollution abatement and control costs are 1% or more of total costs. These include organic chemicals, inorganic chemicals, non-ferrous metals, petroleum products, fertilisers and construction materials.

- Dirty-footloose products: those from industries defined as for the non-resource-based pollution-intensive industries that use few raw materials and which do not need to locate near the sources of raw materials.

- Normal products: those that do not belong in the other two categories.

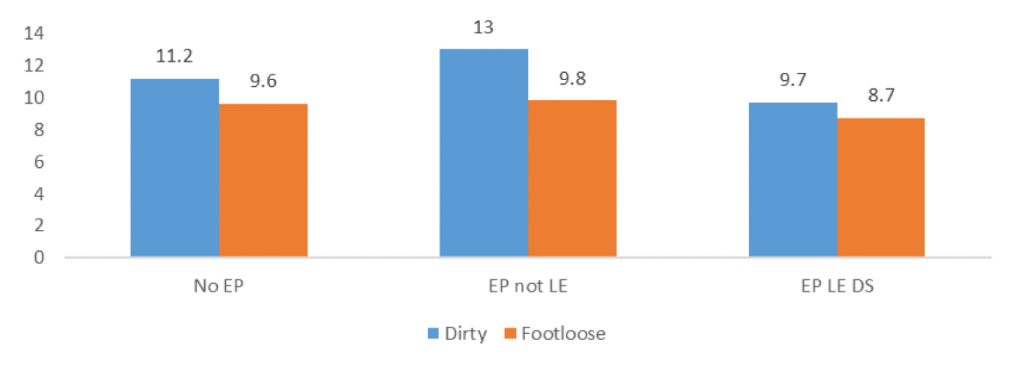

In general, evidence suggests that the existence of a treaty or the enforceability of the environmental provisions can lead to more trade in clean goods. Figure 1 shows that the more stringent the environmental provisions in a trade agreement, the lower the value of trade in dirty goods. Indeed, the shares of dirty goods and dirty-footloose goods decrease from 11.2% and 9.6% to 9.7 and 8.7%, respectively, when legally enforceable provisions subject to dispute settlement are introduced into a trade agreement. This is why it is important to consider the level of enforcement.

Figure 1: Legal enforcement and type of traded goods (%)

Source: Authors’ own elaboration using BACI and Deep Trade Agreement dataset.

Notes: EP stands for environmental provision, LE for legally enforceable and DS for dispute settlement.

Our results show that RTAs with environmental provisions increase trade in non-dirty and non-footloose goods slightly less than RTAs without these provisions by around 5% on average. In contrast, in the case of dirty and footloose categories, RTAs with environmental provisions reduce trade by 18% and 17%, respectively, with respect to RTAs with environmental provisions for non-dirty and non-footloose goods.

When distinguishing by groups of countries and the direction of the export flows, the results show that flows of dirty and footloose goods decrease when RTAs have environmental provisions that are legally enforceable and are subject to dispute settlement. This especially holds for flows from non-OECD to OECD.

Implications for policy

From a policy perspective, this research highlights a couple of policy-relevant findings. First, for developing countries, especially those in the MENA region, there is still a long distance between considering such provisions and actually implementing them. Most of the treaties and trade agreements with environmental provisions are more concentrated in advanced economies, confirming the ‘pollution haven hypothesis’ – the idea that developing countries are the repository for environmentally damaging production.

Thus, deepening trade agreements to go beyond a simple mutual reduction in tariffs is crucial for the MENA region. Indeed, most the agreements involving MENA countries are rather shallow. Including environmental provisions in deeper trade agreements could make the region’s trade policy more in line with the ambitions of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Second, the existence of a law does not necessarily lead to a concrete and tangible effect on trade. In other words, while the de jure dimension is necessary, it is not sufficient.

Thus, making trade laws legally enforceable at the international level and subject to dispute settlement – the de facto dimension – makes them more effective. These results confirm the role of trade policy in efforts to decarbonise the global economy and reach net-zero emissions.

Further reading

Baghdadi, L, I Martínez-Zarzoso and H Zitouna (2013) ‘Are RTA Agreements with Environmental Provisions Reducing Emissions?’, Journal of International Economics 90(2): 378-90.

Brandi, C, J Schwab, A Berger and J-F Morin (2020) ‘Do Environmental Provisions in Trade Agreements Make Exports from Developing Countries Greener?’, World Development 129: 104899.

Martínez-Zarzoso, I, T Núnez-Rocha and C Zaki (2024) ‘Environmental regulations and environmental provisions’ impact on trade’, Revue d’économie du développement (forthcoming).