In a nutshell

Jordan’s debt doubled in the 2000s, but this went largely unnoticed as the debt-to-GDP ratio fell by half due to high rates of economic growth; growth subsided then and the debt-to-GDP ratio more than doubled, private sector growth stalled and social conditions deteriorated.

Reforms aiming to reduce the debt and create sustainable and inclusive development have not produced the expected results as they have not been executed consistently and in a timely manner.

Similar efforts were introduced in the early 2020s after the economy reached a fiscal cliff. Though Jordan faces strong regional and domestic headwinds, current reforms, if successfully implemented, can revive the private sector, improve governance, control public spending, stimulate private sector growth, and promote human development while adopting a more effective social safety net.

Historically, Jordan’s economy has been dependent on workers’ remittances, international aid and, at times, on financial and in-kind support from the country’s oil-rich regional neighbours. After the collapse of oil prices in the early 1980s and the economic crunch that ensued, expansionary policy responses led to an unprecedented increase in public debt, leading to a debt crisis in 1989. Though initially contained, the debt-to-GDP ratio reached nearly 100% in 2000.

There was a substantial but short-lived revival of economic growth following (effectively ‘benefitting from’) the Iraq war in 2003, which reduced the debt-to-GDP ratio to around 60% by 2009. The reduction was purely due to the increase in GDP rather than attempts to reduce the level of borrowing: between 2000 and 2010, the debt doubled from JD6.5 billion to JD12.5 billion.

External shocks have not helped but more could have been done domestically

The end of Jordan’s 2000s boom coincided with the global financial crisis that began in 2008, which was followed by the Arab Spring in 2011, the interruption of Egyptian gas supplies to Jordan in 2012/13, the influx of refugees from Syria’s conflict and from Iraq after the emergence of ISIS, the Covid-19 pandemic starting in early 2020 and, more recently, the food and fuel crisis arising from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine from early 2022.

During the 2010s, Jordan’s debt-to-GDP ratio started to rise again and reached a fiscal cliff at 97% in 2019 and 115% in 2022 (International Monetary Fund, IMF, 2023). Since 1989, the country has gone through six debt restructurings (more than any other Arab country) and IMF-supported programmes in 1989, 1992, 1994, 1997, 1999, 2002, 2012, 2016 and, more recently, in 2020 (Mazarei, 2023). In the last three decades or so, the budget has rarely been balanced or positive, even after grants.

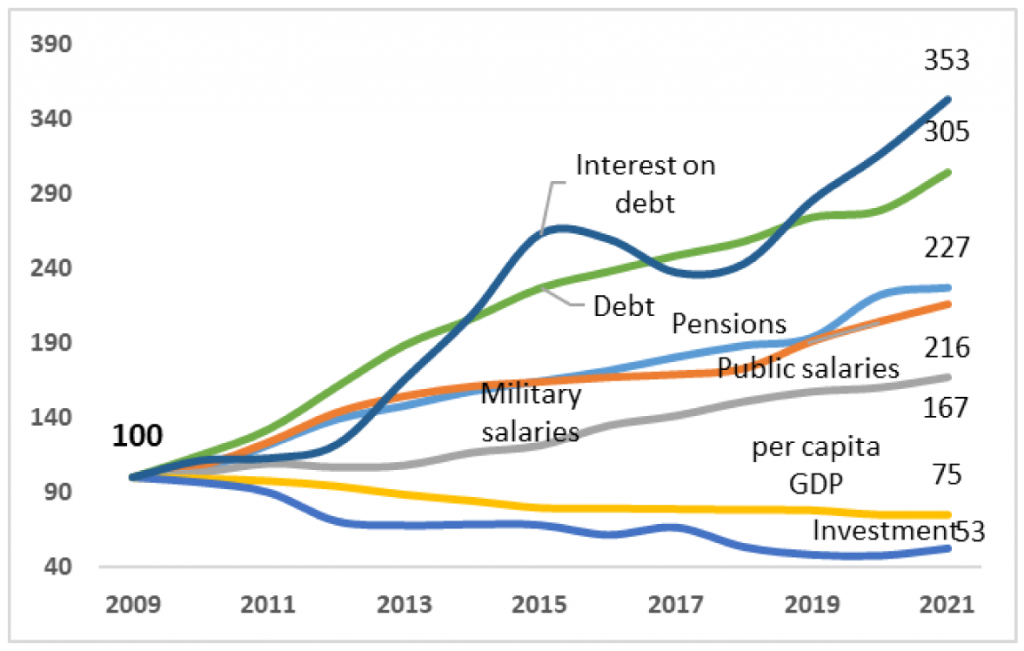

Figure 1: Macroeconomic Indicators 2009-21 ($); Investment (% of GDP); Index 2009=100

Source: Tzannatos and Saif (2023) based on data from the Central Bank of Jordan, Department of Statistics (DOS), IMF, Jordan Strategy Forum, Social Security Corporation and World Bank

A snapshot of key macroeconomic indicators since the end of the 2000s economic boom is in Figure 1. What stands out is that government spending has ballooned not just because of public borrowing but also because of increases in public sector pay and pensions. These trends have been accompanied by a decline in the investment rate by nearly half, along with a reduction in per capita incomes by one-quarter (see below).

Weak macroeconomic management

Outside historical considerations, one of the reasons for the current state of Jordan’s economy is that the ‘roof was not fixed when the sun was shining’ during the boom decade preceding the Arab Spring. It was not that intention was lacking, but many worthy initiatives were not implemented consistently or in full.

One initiative was the ‘Vision 2025’ introduced in 2014 (Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, 2014). That vision aimed to revitalise the economy and reduce the fiscal deficit, unemployment and poverty via three consecutive ‘Executive Development Programs’. The first programme was to conclude by the end of 2018 but it was abandoned after the government changed in 2016.

An ‘Economic Incentive Plan’ was introduced in 2017 with similar objectives to those in ‘Vision 2025’ but it too was short-lived after the 2018 change of government. The plan was followed up by the ‘Reform Matrix’ (2018-24) in agreement with donors and was accompanied by significant external support. The programme was formally adopted in 2020 shortly before the government changed again (Jordan has had eight prime ministers and many more cabinet reshuffles since 2009). In June 2022, an ‘Economic Modernization Vision 2033’ was introduced.

An earlier important initiative was the National Employment Strategy 2011-20 (Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, 2011; International Labour Organization, ILO, 2015). This did not just call for reducing the public/private employment divide and for better management of migration, but it also emphasised that a critical factor in creating decent employment, increasing productivity and reducing unemployment is the dynamism of the private sector. Had the employment strategy not met the fate of other initiatives, it could have contributed to a reduction in unemployment and increase in household incomes.

An anaemic private sector

In addition to failed attempts to reduce Jordan’s debt, private sector performance has been less than impressive. The economy has steadily been moving into lower value-added activities and its structure has been failing to diversify; productivity has been declining (Jordan Strategy Forum, 2018); domestic and foreign investment have been on a declining path; the rate of innovation has been low and also falling (Tzannatos, 2022; Jordan Strategy Forum, 2023a); and economic freedom and the rule of law weakening (Jordan Strategy Forum, 2023b).

One Investor Confidence Survey found that the percentage of investors who see the business environment in Jordan as ‘not encouraging’ increased from 56% in 2017 to 68% in 2022. While a decade ago, nearly 20% of Jordanian firms were five years old or younger, their share had dropped to less than 10% by 2019. The share of politically connected private sector firms is second only to Tunisia and on par with Egypt (Tzannatos and Saif, 2023).

Struggling social sectors

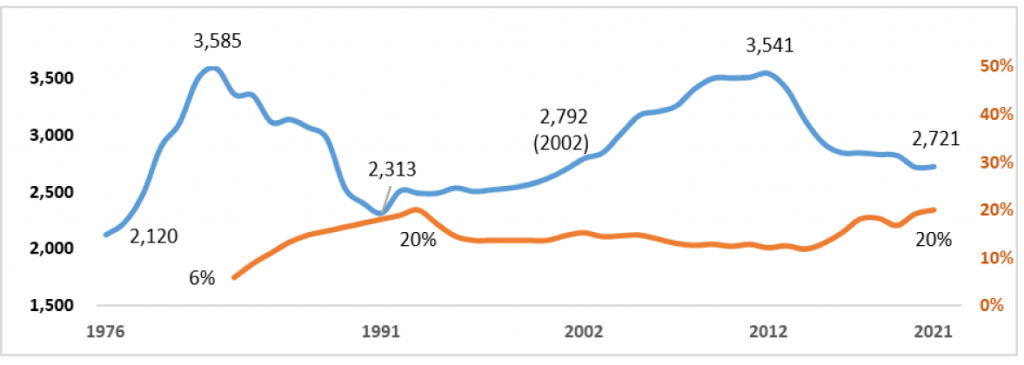

Today, Jordan’s per capita income in real terms is no higher than it was in the late 1970s (see Figure 2). Since 1992, the unemployment rate has been quite stable, while per capita income growth has been positive in only 15 years of the 37 years up until 2019. From the end of the economic boom in 2009 to 2020, per capita incomes declined on average by (minus) 1.5% per year or by 25% overall. The influx of refugees and persisting high fertility rates can only account for less than half of the decline (Tzannatos and Saif, 2023).

Figure 2: Per capita GDP (constant $) and unemployment rate (right axis), 1976-2021

Sources: Department of Statistics (DOS) and World Bank Development Indicators

The toll on household incomes has been compounded by high and persistent unemployment rates not only for youth and women but also for adults and men (Tzannatos, 2021). Private sector wages have barely increased over time except for the lowest as minimum wages (considered to be a kind of social protection) have been rising faster than average incomes. Reduced fiscal space, combined with a drive for privatisation, has also reduced the availability of and access to education, health and social protection (Kawar et al, 2022).

Jordan’s score in the World Bank’s human capital index is lower than the average for the Middle East and North Africa, implying that children ‘born in Jordan just before the pandemic will be 55% as productive when they grow up as they could be if they enjoyed complete education and full health’ (World Bank, 2020).

Like the case of investors, the Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies reports that in 2022, 77% of Jordanians viewed their current economic situation as ‘bad’ or ‘very bad’. That year, another survey by the International Republican Institute indicated that almost 40% believe the country is ‘headed in the wrong direction’, a 24% increase from 2020.

The headwinds may become stronger

The effects of the war in Gaza on Jordan are difficult to predict. But some others can be anticipated with more certainty. Four big-ticket items relate to energy, water, pensions and the environment.

Energy exposes Jordan, an energy-importing economy, to both price fluctuations and import uncertainties from political developments in its neighbours, notably Egypt and Israel. In addition, the domestic National Electricity Company (NEPCO) is characterised by chronic underperformance on top of continuing deficits and legacy debts.

Another predictable pressure comes from the water sector. Jordan remains one of the most water-poor countries in the world: its renewable water supply barely meets two-thirds of the population’s demands, while groundwater is depleted twice as fast as it can be replenished. The Water Authority Jordan (WAJ) also faces persistent losses and arrears. Addressing the water scarcity requires massive investment (IMF, 2022).

Social security constitutes a significant contingent liability. Reforms aiming to rationalise the conditions under which pensions are granted and what their level should be have experienced policy reversals. The IMF (2023) estimates that the inclusion of social security holdings in the government guaranteed debt increases the share of debt-to-GDP by 25%, from 88% to 113%. This share is more than the combined share of education, health and social protection in public spending.

The IMF has estimated that spending on climate adaptation would require another 2% of GDP – a difficult increase in the short run despite its long-term benefits. Also according to the IMF, the public debt ‘is projected to continue on a downward trajectory over the next decade. However, the pace of decline will decelerate after 2027’ (IMF, 2022). The latter year is already two years later than originally envisaged by the 2020 IMF programme, though the delay is not without some justification given the pandemic and the war in Ukraine. The ongoing war in Gaza can make the headwinds stronger and not only from an economic perspective (UNDP/ESCWA, 2023; World Bank, 2023).

Policies: will the future be different?

As in the past, aware of the situation and potential headwinds, Jordan has been pro-active in developing mitigating programmes and development plans. In 2022, King Abdallah II announced an ambitious ‘Economic Modernization Vision 2030: Unleashing the Potential to Build the Future’.

In its first phase, the vision is to be implemented through a ‘2023-25 Government Executive Program’, which initially included 183 initiatives and the approval of 46 legislative items – not a small or simple undertaking (Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, 2023). In the meantime, the King announced the creation of a high-level committee tasked with advancing political reform (Linfield, 2021).

Will this time be different? The IMF’s debt sustainability assessment (DAS) is based on critical assumptions about short-term economic growth and interest rates in the absence of shocks. It also assumes that donor support and the commitment of authorities to the agreed reforms will be the expected one.

The future is uncertain, but what is more certain today is that Jordan is borrowing at a much higher rate than the economy grows. In April 2023, Jordan raised $1.25 billion five-year Eurobond at a rate of 7.5%. This alone undermines sustainability if the economy continues to growth at a rate that is one-third of the government’s debt service obligations. The fact that the share of external debt and its service in total debt has been increasing over time poses additional concerns.

Given that growth is still fragile, unemployment is high and the social sectors are faltering, fiscal consolidation (‘austerity’) needs to avoid a sizeable adverse impact on aggregate demand. In fact, even the role of achieving primary balance has been questioned empirically. The ability of policy-makers to maintain fiscal solvency through higher primary balances in countries with high debt ratios, as in the case for Jordan, has been found to be weak and ‘countries should focus more on accelerating economic growth’ (Mendoza and Ostry, 2008).

In conclusion, Jordan should forcefully pursue what it has known for decades and which is now included in the Economic Modernization Vision 2030: by improving governance; by rationalising, though not necessary reducing, public spending; by reviving the private sector; and by promoting human development and creating a more effective social safety net.

Further reading

Adnan Mazarei (2023) ‘Debt clouds over the Middle East’, The Forum: ERF Policy Portal.

ILO (2015) ‘Jordan: The National Employment Strategy 2011-2020: An Update and Future Directions’, Regional Office for the Arab States (October).

Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan (2011) ‘National Employment Strategy 2011-2020’, Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation.

Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan (2014) ‘Jordan 2025: A National Vision and Strategy’, Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation.

Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan (2021) ‘Jordan’s Reform Matrix 2018-2024: Background and Progress Update’, Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation.

Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan (2022) ‘Economic Modernization Vision: Unleashing the Potential to Build the Future’.

Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan (2023) ‘Cabinet approves executive plan for Economic Modernization Vision’, Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation.

IMF (2022) ‘Article IV Consultation and Fourth Review under the Extended Arrangement under the Extended Fund Facility, Request for Augmentation and Rephasing of Access, and Modification of Performance Criteria’.

IMF (2023) ‘Executive Board Completes the Sixth Review under the Extended Fund Facility with Jordan’

Jordan News (2023) ‘77% of Jordanians report ‘bad’ economic situation in recent survey’.

Jordan Strategy Forum (2018) ‘On the Importance of Labor Productivity in Jordan: Where is the Challenge?’.

Jordan Strategy Forum (2023a) ‘The World Creativity and Innovation Day: The Underlying Challenge Facing Jordan’.

Jordan Strategy Forum (2023b) ‘Where does Jordan Stand in the Rule of Law?’.

Kawar, Mary and Zafiris Tzannatos (2017) ‘Young People Need Jobs, and So Do Their Parents’, Venture.

Kawar, Mary, Zina Nimeh and Tamara Kool (2022) ‘From Protection to Transformation: Understanding the Landscape of Formal Social Protection in Jordan’, ERF Working Paper No. 1590.

Linfield, David (2021) ‘Jordan Could Repair Public Rift with these Five Reforms’, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Mendoza, Enrique, and Jonathan Ostry (2008) ‘International evidence on fiscal solvency: Is fiscal policy “responsible”’?, Journal of Monetary Economics 55(6): 1081-93.

Tzannatos, Zafiris (2021) ‘The Mismeasured, Misunderstood and Mistreated Arab Youth’, in Hassan Hakimian (ed.) Routledge Handbook on the Middle East Economy.

Tzannatos, Zafiris (2022) ‘Job Creation, Innovation and Sustainability in the Arab Countries in the Southern Mediterranean: Will this Time Be Different?’, in IEMed Yearbook 2022, European Institute of the Mediterranean.

Tzannatos, Zafiris and Ibrahim Saif (2023) ‘Assessing the Sustainability of Jordan’s Public Debt: The Importance of Reviving the Private Sector and Improving Social Outcomes’, ERF Working Paper No. 1649.

UNDP/ESCWA (2023). ‘Expected socioeconomic impacts of the Gaza war on neighbouring countries in the Arab region’. December.

World Bank (2020) ‘Jordan: Human Capital Index’.

World Bank and Social Security Corporation (2021) ‘Toward Coverage Expansion and a More Adequate Equitable and Sustainable Pension System’. World Bank (2023). ‘Jordan Economic Monitor Fall 2023’. December.