In a nutshell

This study examines the joint effect of regime change and the war against Iraq on life expectancy in Iran between 1978 and 1988.

The study uses a synthetic control model to construct a counterfactual case for Iran based on a weighted average of other comparable countries, which reproduces the situation of pre-revolution Iran and does not experience the revolution and war.

On average, Iranian's total life expectancy would have been approximately five years longer without the revolution and subsequent war.

Wars and other violent conflicts cause devastating human and economic damage in countries around the world. A large body of research has looked at the effects of such events in Iran (Amirahmadi, 1990; Mofid, 1990; Jahan-Parvar, 2016; Farzanegan, 2022; Farzanegan and Kadivar, 2023). Where war and regime change combine, the price can be particularly high. Looking again at the Iranian case, the joint event of revolution and war resulted in an annual income loss of about $3000 for an average Iranian (Farzanegan, 2022). These estimations do not capture the long-term psychological effects of the experience of war conditions (Farzanegan and Gholipour, 2021). So, in reality, the losses incurred are likely to be even higher.

In addition to economic costs, the human costs of revolution and war need to be quantified. As it stands, no past study has conducted a counterfactual analysis to estimate health indicators in Iran in the absence of revolution and war. While there are review studies – such as Razoux (2015) – which show how many military personnel and civilians were killed or injured as a direct result of the unrest, these numbers do not show the lost years of life caused by the dramatic events.

Addressing this issue is a challenging task. It can be argued that some of the socio-economic factors which led to the revolution (e.g., demographic development, economic conditions, etc.) were also responsible for subsequent changes in the overall health indicators of Iranians. As mentioned by Holland (1986), one of the main problems of causality analysis is that the unit of intervention (Iran in this case) cannot be obtained without that specific treatment (revolution & war in our example). In other words, it is impossible to view the unit of interest with and without treatment at the same time. So, the challenge of causal analysis is in the estimation of a synthetic unit which best reproduces the factual unit of interest under treatment. It is a difficult research question, but one with important answers for assessing the true damage of conflict.

Measuring the impact of the conflict

By using the synthetic control method (Abadie, 2021) (SCM), it is possible to study the trajectory of longevity in Iran before and after the Islamic Revolution. This method relies on a weighted average of control units to create a counterfactual case for Iran. If the ‘synthetic Iran’ adequately represents the pre-revolutionary period, any deviations between ‘actual Iran’ and the counterfactual case after the revolutionary event can be attributed to the causal impact of the revolution and the war on Iranians’ life expectancy.

The health outcome in this study (Farzanegan, 2023) is life expectancy at birth. This refers to ‘the average number of years a new-born is expected to live if mortality patterns at the time of its birth remain constant in the future’. The selected predictors of this outcome, which also help to find a more relevant counterfactual for Iran, are per capita expenditure-side real GDP at chained PPPs (in 2017 US$), share of government spending in GDP, population growth rate, and the age dependency ratio. It is also necessary to control for previous records of life expectancy in the years 1976, 1974, 1972, 1970, 1968 and 1966, to help increase the goodness of fit of the counterfactual Iran with factual Iran during the pre-revolution and war periods.

The study uses a panel of data from 1965 to 1988. The treatment year is 1977 when the open resistance against the Shah started. The donor sample from which counterfactual Iran is generated was from the MENA and OPEC countries. For the outcome of total life expectancy, the counterfactual Iran is generated by the following countries, ordered by their respective weights: Saudi Arabia (61.5%), Nigeria (25.2%), Malta (6.8%) and Egypt (6.8%).

How did the revolution and war affect life expectancy?

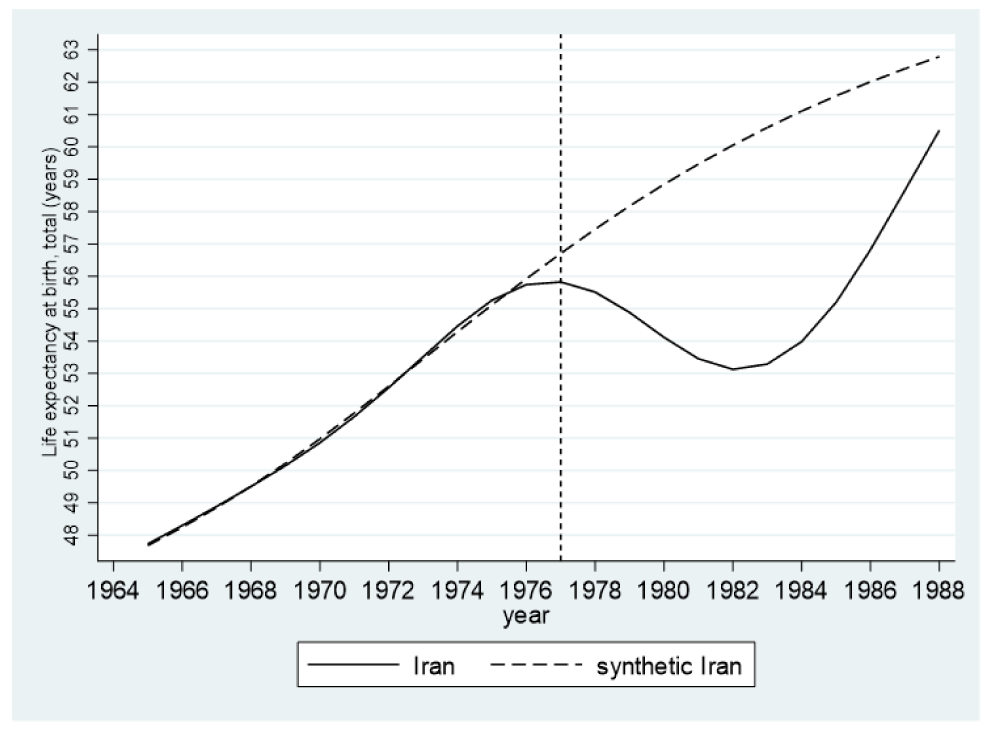

Figure 1 illustrates the total life expectancy trends of both factual Iran and its synthetic counterpart from 1965 to 1988. Throughout the entire pre-revolution period, the synthetic Iran closely mirrors the life expectancy pattern of factual Iran. But starting in 1977 (the beginning of revolutionary movements, as explained by Kurzman 2005)), a noticeable divergence between the two lines becomes evident. While life expectancy growth in actual Iran decelerates, the synthetic counterpart maintains a steady upward trajectory (similar to the pre-revolution era). This implies a notable negative effect caused by the war and revolution.

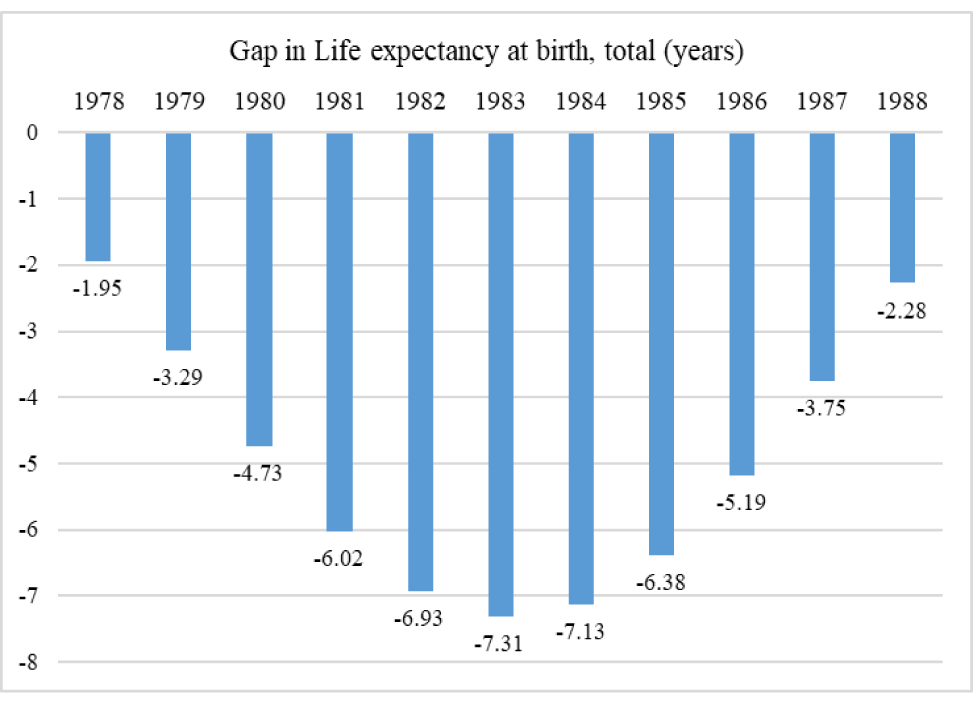

The analysis reveals an average annual decline of five years in total life expectancy from 1978 to 1988. In simpler terms, in the absence of the revolution and subsequent war, a typical Iranian’s life expectancy would have been extended by five years. The gap between the two lines continues to widen until the middle of the war with Iraq (1983-84), but starts to narrow towards the end of the conflict (1988). This suggests that while the revolution had a moderate long-term impact on total life expectancy at birth, the most substantial impact can be attributed to the war itself. The findings highlight a significant adverse influence of both internal and external violence on the life expectancy of Iranians. Notably, the estimated negative impact of the revolution and war in Iran surpasses the average negative effect of UN sanctions on life expectancy, which is approximately 1.2-1.4 years in a global sample (Gutmann, Neuenkirch and Neumeier, 2021).

Figure 1. Life expectancy at birth (total years). Factual Iran versus counterfactual (synthetic) Iran

The difference in life expectancy between factual and counterfactual Iran is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Estimated lost years of life for Iran under revolution and war

The study also explores the potential factors underlying the significant decline in life expectancy. These events had a more profound impact on health indicators such as life expectancy and adult mortality rates for the male population. The gap between male and female life expectancy widened mainly due to excess male adult mortality rates. In short, men were more likely to be killed fighting, and this is the central factor explaining the difference between the factual and counterfactual cases.

Conclusion

The average annual loss in life expectancy from 1978 to 1988 is estimated to be five years. In other words, had there been no revolution and war, the life expectancy of an average Iranian would have been five years longer. This result further emphasises the appalling damage caused by war and other violent conflicts and grants new evidence for policy-makers considering imposing sanctions in the face of new potential wars.

Further readings

Abadie, Alberto. 2021. “Using Synthetic Controls: Feasibility, Data Requirements, and Methodological Aspects.” Journal of Economic Literature 59 (2): 391–425. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20191450.

Amirahmadi, Hooshang. 1990. “Economic Reconstruction of Iran: Costing the War Damage.” Third World Quarterly 12 (1): 26–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436599008420213.

Farzanegan, Mohammad Reza. 2022. “The Economic Cost of the Islamic Revolution and War for Iran: Synthetic Counterfactual Evidence.” Defence and Peace Economics 33 (2): 129–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2020.1825314.

Farzanegan, Mohammad Reza. 2023. “Years of Life Lost to Revolution and War in Iran.” Review of Development Economics, 1-43. https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.13030

Farzanegan, Mohammad Reza, and Hassan F. Gholipour. 2021. “Growing up in the Iran–Iraq War and Preferences for Strong Defense.” Review of Development Economics 25 (4): 1945–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.12806.

Farzanegan, Mohammad Reza, and Mohammad Ali Kadivar. 2023. “The Effect of Islamic Revolution and War on Income Inequality in Iran.” Empirical Economics. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3971303.

Gutmann, Jerg, Matthias Neuenkirch, and Florian Neumeier. 2021. “Sanctioned to Death? The Impact of Economic Sanctions on Life Expectancy and Its Gender Gap.” The Journal of Development Studies 57 (1): 139–62.

Holland, Paul W. 1986. “Statistics and Causal Inference.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 81 (396): 945–60. https://doi.org/10.2307/2289064.

Jahan-Parvar, Mohammad R. 2016. “The Cost of a Revolution.” Iran Nameh 30 (4): LXXVIII–CI. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2144857.

Kurzman, Charles. 2005. The Unthinkable Revolution in Iran: Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Mofid, Kamran. 1990. The Economic Consequences of the Gulf War – 1st Edition – Kamran Mofid. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/The-Economic-Consequences-of-the-Gulf-War/Mofid/p/book/9781138968226.

Razoux, Pierre. 2015. “The Iran-Iraq War.” In The Iran-Iraq War. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674915701.