In a nutshell

Double-digit food inflation is weighing heavily on developing economies across the MENA region, with poorer groups being hit hardest by food price hikes. Average year-on-year food inflation between March and December 2022 was 29% in the MENA region – far higher than headline inflation (19.4%).

This poses challenges to a region that already struggled with inadequate child nutrition and health, even before the Covid-19 pandemic or the war. Initial rates of stunting—which is recognised as a measure of the cumulative impact of health deficiencies in a child from pre-birth to age five—are much higher for many countries in the region relative to their income peers.

Billions of dollars are needed annually to meet the projected development financing needs for the severely food insecure in the MENA region. But there are significant advantages to investing in resilience and tackling chronic food insecurity before it escalates into full blown crises. The time to act is now.

Growth in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region is slowing. The World Bank’s (MENA Economic Update forecasts that growth in the region will be 3% in 2023, down from 5.8% in 2022. The slowdown is concentrated in Gulf Cooperation Council economies (GCC) that benefitted from oil windfalls in 2022 (GCC GDP growth fell from 7.3% in 2022 to 3.2% in 2023). In addition to falling incomes, the purchasing power of the people living in MENA countries was also eroded by sharp price increases. Double-digit food inflation is weighing heavily on developing economies across the region, with poorer groups being hit hardest by food price hikes.

Rising food prices are making it difficult for families to put meals on the table. Inflation hits the poor much harder than the rich due to the disproportionate share of family expenditures devoted to food and energy. Average year-on-year food inflation between March and December 2022 was 29% in the MENA region – far higher than headline inflation (19.4%). Food price inflation reached double digits for most of the low- and middle-income MENA economies in 2022. In December 2022, poorer households experienced inflation that was about 2 percentage points higher than that experienced by rich households on average across developing MENA economies.

Increases in food prices, even if temporary, can cause long-term, irreversible damages, especially to children. Negative shocks can have multi-generational effects on development outcomes including education, health, income and other areas (Almond and Currie, 2011; Almond et al., 2018). Beyond the immediate health effects, inadequate nutrition in utero and early childhood can disrupt the destinies of children, setting them on paths to limited prosperity. The region’s population is younger than any but that of sub-Saharan Africa. This means food insecurity may cause extensive harm as it reverberates through children in the region.

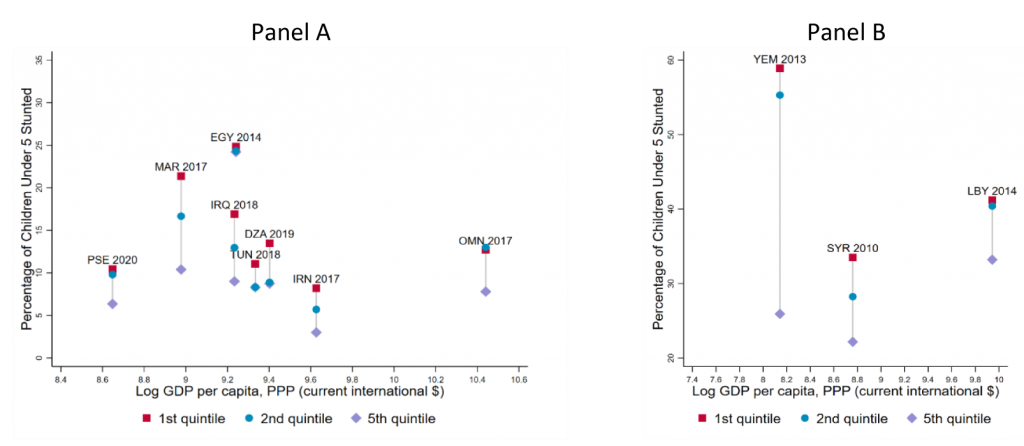

Food insecurity poses challenges to a region that already struggled with inadequate child nutrition and health, even before the Covid-19 pandemic or the war in Ukraine. Initial rates of stunting—which is recognised as a measure of the cumulative impact of health deficiencies in a child from pre-birth to age five—are much higher for many countries in the region relative to their income peers.

But the average country stunting rates mask considerable differences within countries. The gap between the stunting rates of the richest and poorest households in the region has historically been large. An extreme case of this was in Yemen before the economic collapse. On average, poor households had stunting rates close to 60%, while rich households had stunting rates less than half of that (Figure 1). The dietary composition of food for children is limited and the widespread presence of subsidies may have distorted household food expenditures toward items that are less nutritious. This manifests itself in the double burden of malnutrition – child obesity and undernutrition are prevalent side-by-side in many MENA economies.

Figure 1: Prevalence of stunting by wealth quintile in MENA

Sources: The Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates (JME) database survey estimates maintained by UNICEF, the World Health Organization (WHO) and The World Bank, May 2022, and the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI).

But much of the data on child health and nutrition in MENA are dated. Only 11 of the 19 economies in the region have had the relevant household survey since 2015. Because of compounded shocks from the pandemic, conflict, debt default, and food insecurity, collecting key anthropometric data—such as height and weight— is urgent to create effective policy action to build back losses in human capital for children.

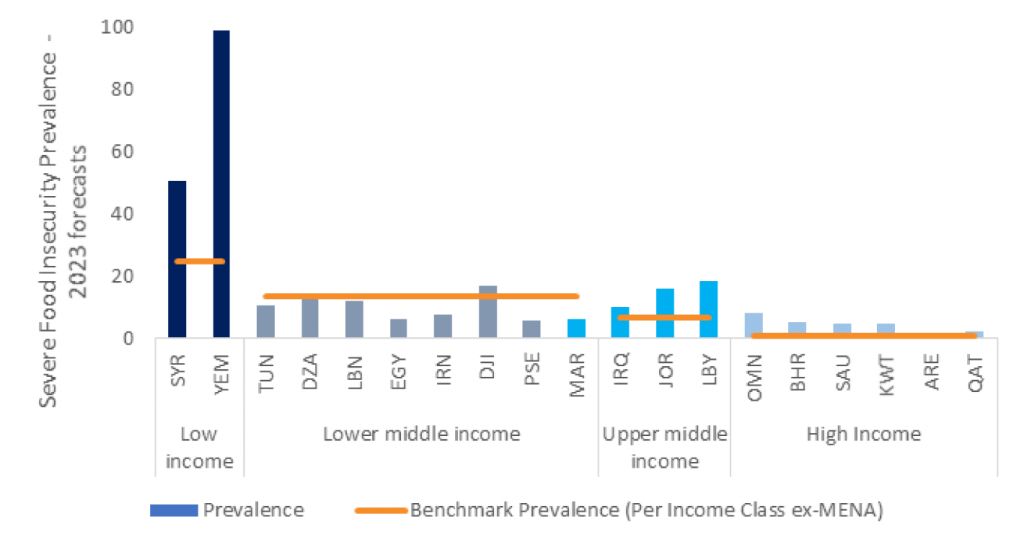

The report uses data from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and machine-learning techniques to estimate food insecurity across countries and over time. The results suggest that almost one out of five people living in the MENA region is likely to be food insecure in 2023, up from about one in ten in 2006. This change is largely due to the situations in Syria and Yemen. Figure 2 shows that most MENA economies have double-digit rates of food insecurity prevalence. Low-income economies such as Syria and Yemen have considerably higher food insecurity prevalence than their income peers. Further, upper-middle- and high-income countries in the region have food insecurity prevalence rates that are higher than their non-MENA income peers. Inflation is a big part of the story: across all four MENA subgroups — developing oil importers, developing oil exporters, conflict countries and the GCC countries — inflation accounts for 24-33% of 2023’s forecasted food insecurity.

Figure 2: Prevalence of severely food insecure people in MENA

Source: Andree, B.P.J. (2022): Machine Learning Guided Outlook of Global Food Insecurity Consistent with Macroeconomic Forecasts. Note that Lebanon is a unique situation that was reclassified from upper to lower-middle-income in 2021. Lebanon performs worse than income peers if placed in the upper-middle-income grouping.

The population of the MENA region is relatively young compared with that of other regions. Estimates presented in the report suggest that about 8 million children under five years of age in the region are severely food insecure. Unfortunately, this is likely to be a conservative estimate because food insecurity disproportionately affects the poor, and the poor in the region tend to have more children. The report uses estimates from Woldemichael et al., (2022) to calculate the effect of food prices on the risk of stunting. The rise in food prices associated with the Russian invasion of Ukraine may have increased the risk of stunting by 17-24%. This translates to between 200,000 and 285,000 babies at risk of stunting in developing MENA economies.

The challenge of food insecurity is enormous. According to the estimates presented in the report, billions of dollars are needed annually to meet the projected development financing needs for the severely food insecure in the MENA region. But there are significant advantages to investing in resilience and tackling chronic food insecurity before it escalates into full blown crises.

There are also several policy tools that can help alleviate food insecurity. Some policies, such as cash and in-kind transfers, can be enacted immediately, stemming acute situations of food insecurity. Others may take longer to implement—such as policies aiming to enhance maternity leave, childcare, medical care, and food systems. Importantly, the report finds the region’s data systems are currently ill-equipped to monitor and track the rising threat of food insecurity. The time to act is now. Policy-makers cannot afford to fail the future generations of the MENA region.

References

Almond, D., and Currie, J. (2011). “Killing Me Softly: The Fetal Origins Hypothesis.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(3), pp. 153-172

Almond, D., Currie, J., and Duque, V. (2018). “Childhood Circumstances and Adult Outcomes: Act II.” Journal of Economic Literature, 56(4), pp. 1360-1446.

Gatti, R., D. Lederman, A. M. Islam, F. R. Bennett, B. P. J. Andree, H. Assem, R. Lotfi, and M. E. Mousa (2023). Altered Destinies: The Long-Term Effects of Rising Food Prices and Food Insecurity in the Middle East and North Africa. MENA Economic Update; April 2023. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Woldemichael, A., Kidane, D., and Shimeles, A. (2022). “Food Inflation and Child Health.” The World Bank Economic Review, 36(3), pp. 757–773.