In a nutshell

The economic impact of natural disasters – including the recent earthquakes in Türkiye and Syria – depends on the destruction they cause, pre-existing economic conditions and the ability of a country to reallocate its resources towards reconstruction.

Poorer economies, such as those with lower levels of government spending and weaker institutions, are more likely to experience larger negative effects on growth.

For Türkiye, it is likely that the overall impact of the latest disaster on economic growth will be less than one percentage point of output in 2023, against the backdrop of a significant increase in government expenditure.

On 6 February 2023, a series of earthquakes – the largest measuring 7.8 magnitude – hit regions in south and central Türkiye and in the north and west of Syria. Over 50,000 people have been killed and thousands more remain missing.

Alongside devastating loss of live, natural disasters, such as this, can inflict serious damage on economies. They destroy equipment, buildings and infrastructure, and disrupt production.

But the precise extent to which these events affect economic output is widely debated.

Some experts argue that earthquakes (and natural disasters in general) have significant negative effects on economic growth (Barro and Martin, 2003; Raddatz, 2009). Recent research also highlights serious indirect effects, as the economic damage spreads through trade networks and supply chains – something economists call ‘spillover effects’ (Teh et al, 2011; Ruta et al, 2021).

But others find mild or even positive effects on growth (Albala-Bertrand, 1993; Loayza et al, 2012; Porcelli and Trezzi, 2019; Skidmore and Toya, 2002).

The economic impact of natural disasters, including these recent earthquakes, depends on the destruction they cause, pre-existing economic conditions and the ability of a country to reallocate its resources towards reconstruction (Hallegatte et al, 2022).

Poorer economies, such as those with lower levels of government spending and weaker institutions, are more likely to experience larger negative effects on growth (Cavallo et al, 2013; DuRose, 2023; Lackner, 2018; Noy, 2009; Toya and Skidmore, 2007).

What can we learn from other countries’ experiences with major earthquakes?

Looking at evidence from 40 major earthquakes across 25 countries, it is possible to make predictions about how a disaster might affect a country’s economic performance.

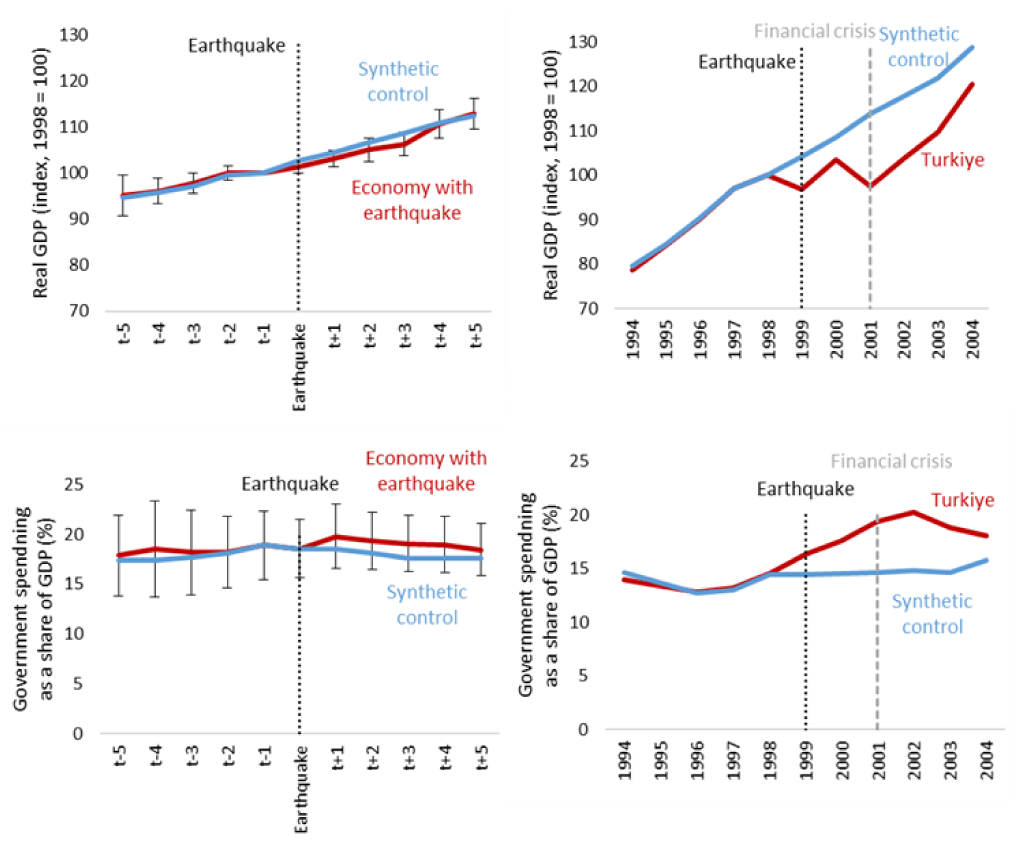

Drawing on data from past earthquakes with at least 1,000 fatalities – including those in Chile, Colombia, Haiti, India, Indonesia, Italy and Japan – shows that in the year after an earthquake, GDP is, on average, around one percentage point lower in the affected economy than in otherwise similar countries (see Figure 1, left-hand panels).

This drop is short-lived, as substantial reconstruction efforts boost GDP, including through increases in government spending. The findings from this research are consistent with earlier studies that examine the effects of natural disasters more generally (Cavallo et al, 2013).

Figure 1: Estimates of the impact of earthquakes on GDP and government spending

Sources: Maddison Tables, Penn World Tables and authors’ calculations.

Notes: Synthetic control refers to a growth path estimated had the earthquake not occurred based on a weighted average of economies that were similar to the economy experiencing the earthquake before it occurred in terms of GDP per capita, population, population density and growth of GDP or government spending. Left panels are based on a sample of 41 earthquakes for GDP and 23 earthquakes for government spending; 90% confidence intervals shown.

GDP is a fairly narrow measure of the economic impact of a disaster. Looking instead at the total difference between companies’ rate of return and their costs for capital investment (known as ‘value added’) across an economy during a given year includes the cost of reconstruction in the calculation. But it leaves aside the cost of damage to physical assets or people’s health. Those costs can be large. Current estimates of direct damage to Turkish homes, factories and infrastructure after the 2023 earthquakes range between $25-$35 billion (JP Morgan, 2023; World Bank, 2023).

What were the effects of the 1999 earthquake on Türkiye’s GDP?

It is possible to use the same research method to construct a counterfactual for Türkiye’s economy after the 1999 earthquake (that is, to imagine what the economy would be like had the earthquake not happened).

But it is important to note that in early 1999, before the earthquake hit, Türkiye’s economy was already performing poorly following a sustained period of economic uncertainty. That year, quarter-on-quarter growth was negative and it was predicted to be just 0.5% for the year, according to a report by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) published in July 1999, the month before the earthquake (IMF, 1999).

The right-hand panels of Figure 1 show that GDP (in constant prices) dropped sharply in 1999. This then rebounded in 2000, boosted by a sharp rise in government spending on reconstruction activities.

Despite the impetus from the disaster response spending, these results suggest that Türkiye’s growth performance over a two-year window was 4.6 percentage points weaker than could be expected based on the non-earthquake scenario (the counterfactual).

This estimate does not consider the weak performance observed in the first half of 1999. Ignoring this changes the picture slightly: it suggests that the estimated economic impact is around 0.9% of GDP.

This negative impact is somewhat higher than estimates in other studies, which suggest a loss of 0.5-1% of GDP in the year that the earthquake occurred, followed by a boost of 1.5 percentage points in the following year (Bibbee et al, 2000).

How do the 1999 and 2023 earthquakes compare?

The 1999 earthquake was a slightly lower magnitude (7.6) than those in 2023, but it occurred in Türkiye’s industrial heartland. The four regions worst affected in 1999 (Kocaeli, Sakarya, Bolu and Yalova) contained only about 4% of the country’s population, but were directly responsible for around 7% of GDP and 14% of industrial value added. They had significant economic links with the rest of the country, including Istanbul (Türkiye’s largest city) and Bursa (the fourth largest city).

As a result, there was significant damage to energy, transport and communications infrastructure in the broader region (Bibbee et al, 2000). Together, the regions that experienced major disruptions because of the earthquake accounted for 35% of GDP and half of industrial output.

The initial economic slowdown resulted from disrupted supply chains; damage to factories, machines and stored foods (loss of physical capital and inventory); death and injury of workers (loss of labour force); and lower investment in the immediate aftermath of the earthquake.

In addition, many small businesses failed because they did not have earthquake insurance. This had a knock-on effect on the banking sector, which saw a sharp increase in defaults on loans in the run-up to the 2001 financial crisis (Bibbee et al, 2000). On the other hand, reconstruction activities did boost growth in 2000.

The 2023 earthquakes in Türkiye are different from that of 1999 in several important respects. The wider region hit hardest by the latest earthquakes was south-east Türkiye (Kahramanmaraş, Gaziantep, Malatya, Diyarbakır, Kilis, Şanlıurfa, Adıyaman, Hatay, Osmaniye and Adana).

These areas experienced substantial damage to pipelines, roads, airports and electricity infrastructure, including a major fire in İskenderun port (Türkiye’s largest shipping port). But the economic links between the affected areas and the rest of the country are more limited than in 1999.

The affected areas are home to 15% of the country’s population but only contribute approximately 9% of GDP and 10% of industrial value added. The region’s contribution to agricultural value added is higher (at 15%), although interruptions to agricultural production are likely to be mitigated by the fact that the earthquake occurred in winter (Kelly and Kóczán, 2023).

Unlike in 1999, the 2023 earthquakes occurred early in the year. As a result, the impact of the reconstruction on the economy will materialise largely in the same calendar year, offsetting the negative effect of disruptions on GDP to a significant extent. In addition, as earthquake insurance has become more widespread since 1999, the impact on the banking sector is expected to be more limited.

What might be the economic effects of the 2023 earthquakes?

The economic impact will depend to a significant extent on the fiscal response. Policy-makers have the capacity to fund various support measures as the level of public debt (and the cost of servicing it) remain modest relative to GDP.

The World Bank estimates the direct damage from the earthquakes at $34.2 billion, with reconstruction costs accounting for emergency response and a surge in the costs of construction amounting to twice as much (World Bank, 2023). At the time of writing, the Turkish government has pledged more than $5 billion towards the recovery effort. International support will also help to finance reconstruction.

Overall, comparing analysis of the 1999 and 2023 earthquakes, it is likely that the overall impact of the latest disaster on economic growth will be less than one percentage point of output in 2023, against the backdrop of a significant increase in government expenditure. But these estimates are subject to major uncertainty as recovery efforts continue.

This column was first published at the Economic Observatory. The original version is here.