In a nutshell

Curbing corruption is not a simple matter of increasing the number of women ministers or parliamentarians: the link between gender and corruption link is strongly context-dependent, especially in the MENA region.

Although there is no evidence that women are intrinsically less corrupt than men, greater gender egalitarianism can break down the male-dominated network of corruption widespread in all MENA countries.

Measures implemented in many MENA countries to empower women in the political and economic sphere must continue to tackle gender discrimination and create societies where meritocracy and impartiality are the foundations of good governance.

In the early 2000s, two seminal World Bank studies (Dollar et al, 2001; Swamy et al, 2001) showed that less corruption is associated with higher women’s involvement in public life – thereby portraying women as ‘the fairer sex’.

The statistical results in this work are in line with strategies implemented in many cities, including in Mexico and Peru, where authorities feminized all traffic police in the late 1990s to curb corruption. More recent research (Gotez, 2007; Bauhr and Charron, 2020) adds nuance to these findings and suggests that women’s influence on corruption cannot be attributed to biological or physical differences.

Why women are less prone to corruption?

Several arguments have been raised to oppose the idea that women are intrinsically more honest than men. The relationship between corruption and women is rather context-dependent and linked to social, economic, cultural and political factors.

Fairer sex versus fairer system

The main argument against ‘fairer sex’ was a ‘fairer system’. The effect of gender on corruption depends on the political system. Indeed, liberal democracy that promotes equality, fairness and meritocracy improves women’s political participation and discourages corruption through the role of the opposition candidates, an independent judiciary and free journalism.

Hence, it is evident that democratic countries that promote women to higher-level positions in politics, government and the public sector have a lower level of corruption.

Risk-aversion versus risk appetite

An alternative line of research argues that the risk-averse attitude that characterises women is also put forward to explain the gender-corruption relationship. This argument is further reinforced by the fact that women are more severely punished when engaging in corruption.

This is the case of scandals linked to women in power, particularly in Latin American countries. Some experimental studies have also shown that women accept bribes less than men when there is a high probability that bribery will be discovered and punished, but there is no gender difference when corruption is a free risk.

Opportunity versus behaviour

The gender-corruption relationship can be also explained by a difference in terms of opportunities presented to women rather than different behaviour towards corruption. Indeed, women have generally been excluded from ‘male-dominated patronage’ and greed-corruption networks.

The lack of knowledge regarding how to take part in corruption activities may explain the gender differences in attitudes.

Selfishness versus selflessness

It is usually considered that the political agendas of women are usually different from those of men. The main issues on which women legislators focus are those linked with public services and social spending relevant to the needs of their gender, such as healthcare and education.

So, women can reduce corruption, not necessarily because they are less corrupt but by pushing forward a political agenda for effective public services, which reduces corruption.

Does the gender-corruption relationship matter for the MENA region?

Compared with other world regions, MENA has the lowest performance in terms of corruption and women’s involvement in public life. There is evidence that in this area there has been progress in eliminating gender disparities in education and health, although gaps remain in the economic and political sphere.

Indeed, according to the World Bank, in 2021, four out of five working-age women were out of the labour force in the region. Moreover, despite the establishment of legal quotas, either for the candidate list (Algeria and Tunisia) or for reserved seats (Iraq and Saudi Arabia), the representativeness of women in politics has not improved. As reported by Inter-parliamentary Union, the region has the lowest representation of women worldwide with just 16.9% of parliamentary seats in 2021.

These poor performances in terms of corruption and the involvement of women in public life strengthen the existence of a correlation between these two phenomena in the region. As mentioned above, the gender-corruption link depends strongly on the country’s context and women’s risk aversion. Political instability, the dominant patriarchal structure, and traditions that often discriminate against women in MENA countries can undoubtedly reinforce this relationship.

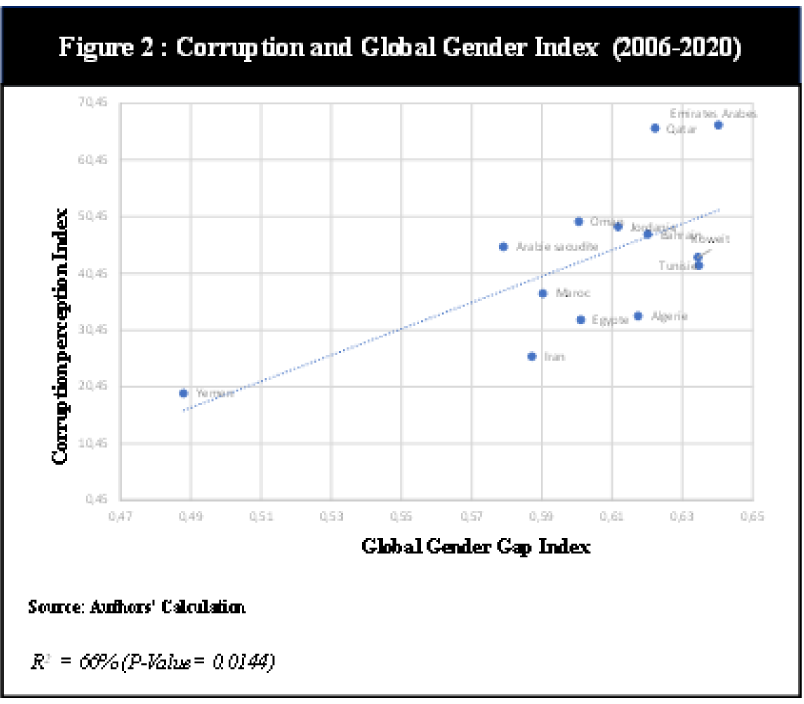

Using a sample of 13 countries in the MENA region between 2006 and 2020, our research shows that there is a correlation between higher participation of women in the economic and political sphere and lower corruption (Jaidane-Mazigh et al, 2022). Although it starts out weak (see Figure 1), this relationship was reinforced when we took into account the context and the type of political regime.

Our findings reveal that a democratic and politically stable framework widely influences the gender-corruption relationship. Indeed, the joint impact of women’s participation in public life and institutional variables is more effective in lowering corruption, especially for women’s participation in the exercise of political power.

Furthermore, we find that the magnitude of the correlation between women’s involvement in the economic and political sphere and corruption increases when adjusted for the gender gap index. It turns out that this index, which measures the gap between men and women in different areas, is strongly correlated with the corruption perception index in our sample (see Figure 2).

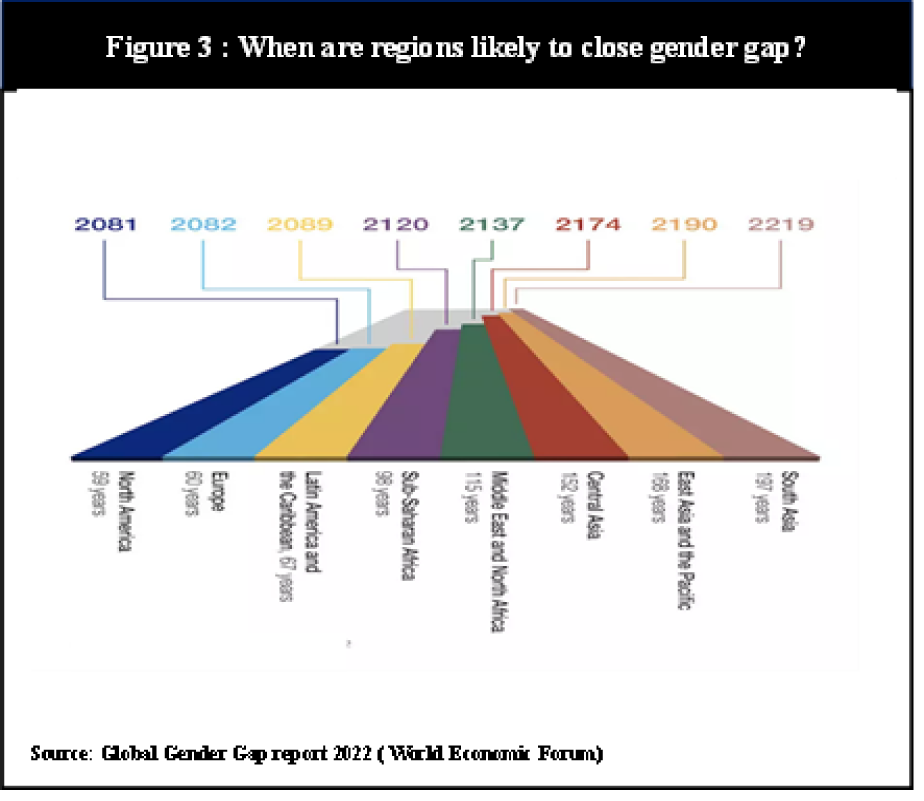

According to the World Economic Forum (2022), despite the performance of some countries such as Lebanon and the United Arab Emirates, MENA has the second largest gap to close after South Asia with an average population-weighted score of 63.4%. This gives the region a timeframe to close the gap of 115 years (see Figure 3). In these conditions, women are highly motivated to counter corruption because it can be the origin of the inequalities from which they suffer.

Policy perspectives

Our results show that curbing corruption is not a simple matter of increasing the number of women ministers or parliamentarians. The gender-corruption link is strongly context-dependent, especially in the MENA region. The lack of democracy, the political instability, and the strong gender inequality, which is mainly due to the patriarchal culture rooted in the region, can challenge any anti-corruption policies.

But although there is no evidence that women are intrinsically less corrupt than men, greater gender egalitarianism can break down the male-dominated network of corruption widespread in all MENA countries.

The different measures implemented in many MENA countries to empower women in the political and economic sphere must continue to tackle gender discrimination and create societies where meritocracy and impartiality are the foundations of good governance.

Due to the complexity of the phenomenon of corruption and its many facets, further research would need disaggregated corruption indexes to capture the gender dimension and to introduce particular forms that have a greater impact on women.

Further reading

Bauhr, M, and N Charron (2020) ‘Do men and women perceive corruption differently? Gender differences in perception of need and greed corruption’, Politics and Governance 8(2): 92-102.

Dollar, D, R Fisman and R Gatti (2001) ‘Are women really the “fairer” sex? Corruption and women in government’, Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 46(4): 423-29.

Goetz, AM (2007) ‘Political cleaners: Women as the new anti‐corruption force?’, Development and Change 38(1): 87-105.

Jaidane-Mazigh, L, I Khefacha and B Smiri (2022) ‘Gender and Corruption in MENA Countries: New Evidence from the ARDL Approach’, ERF Working Paper No. 1611.

Swamy, A, S Knack, Y Lee and O Azfar (2001) ‘Gender and corruption’, Journal of Development Economics 64(1): 25-55.

United Nations Offices On Drugs and Crime (2020) The Time is Now: Addressing the Gender Dimensions of Corruption.

World Economic Forum (2022) Global Gender Gap Report.