In a nutshell

Reasons for the limited creation of good jobs in Arab countries include weak regulatory frameworks, underdeveloped labour market institutions, inadequate fiscal space, concentration of economic activity in low-productivity sectors and political instability.

Key areas for policy action start with an immediate structured response to the challenges resulting from the pandemic, stimulating the economy through more expansionary fiscal and monetary policies.

Comprehensive national employment policies are vital for addressing structural, longstanding and multidimensional labour market challenges, including inefficiencies of the private sector and its limited potential and capacity to create decent jobs.

The Arab region has four endemic labour market challenges: high unemployment; widespread informality; low growth in total factor productivity; and extremely low labour force participation.

These stylised facts were supposed to have disappeared with the onset of economic reforms in the early 1990s. One thing these reforms did very successfully in most countries is to impose strict limits on public employment. But one thing they were supposed to do and failed at is to induce job creation in the formal private sector, leaving low value-added sectors to absorb the bulk of employment demand by the youth.

The result is that the majority of employed youth, typically better educated than older cohorts were decades ago, have to deal with low paying, informal jobs. The youth bulge, normally an opportunity, now presents itself as a both a political and development challenge in all Arab countries, rich and poor.

What has led to this peculiar set of stylised facts? A recent report from the Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) and the International Labour Organization (ILO) attempts to answer this question by studying characteristics of formal enterprises in several Arab countries over the past two decades (ESCWA and ILO, 2021).

The report finds that besides the weak governance structures across all non-oil Arab states, formal private sector firms in Arab countries suffer from four overlapping labour market challenges: job creation, inequality, productivity and technology.

The job creation challenge

First, employment in the formal private sector in the Arab region is growing at a weighted annual average of 2%. The formal private sector in the region is insufficiently diversified and lacks the required structure to absorb the large numbers of new labour market entrants. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have the lowest annual employment growth of 1%, while employment in large firms is growing at around 3.5% annually.

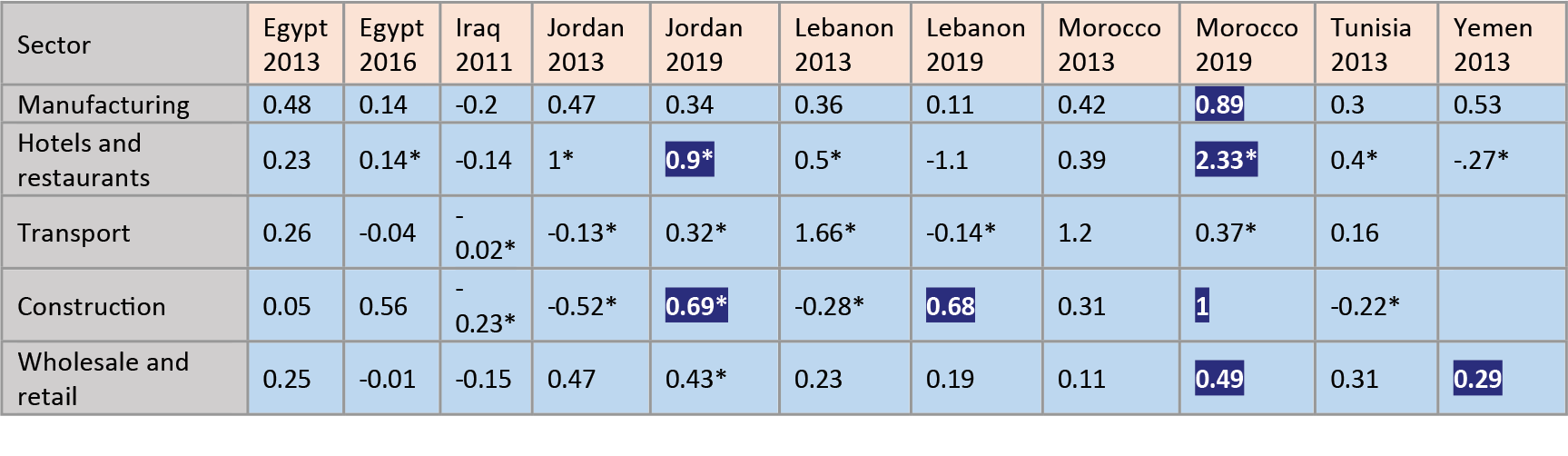

Thus, unlike the rest of the world, employment elasticity in the formal private sector is low in the region, and significantly lower than the average income for most Arab countries, with Iraq experiencing negative employment elasticity in all sectors (see Table 1). Overall, most sectors in all Arab countries (except Morocco) have an employment elasticity below 1 (and many below 0.5), indicating that an increase in output by 1% increases employment by less than 0.5%.

Moreover, firms’ employment elasticities in most Arab countries are below those of non-Arab countries with similar income brackets. These elasticities tend to change over time depending on changes in the economy.

Table 1: Employment elasticities in selected Arab states

Source: ESCWA and ILO (2021) based on the World Bank Enterprise Survey datasets.

Note: An asterisk (*) indicates that the number of observations is less than 50.

Highlighted values are elasticities above the country’s income bracket peers.

To understand the order of magnitude of the job creation challenge the following factors should be taken into account:

- Before the pandemic, 33.3 million new jobs needed to be created in the Arab region to reduce the unemployment rate to 5% by the end of 2030. This number will double if the rate of women’s participation in the labour market rises to global averages. But these projections do not factor in the employment repercussions of the pandemic and the impact of the Fourth Industrial Revolution on the region’s skill mismatch.

- According to the ILO COVID-19 Monitor, nearly one-third of the employed population in the region is facing high risks of layoffs or reduced wages and/or working hours owing to the pandemic. As global economies are hit hard by the pandemic, the region is struggling to respond to labour market repercussions. An estimated 39.8 million individuals in the Arab region are employed in sectors that are identified as most-at-risk. Furthermore, 12.8% of working hours are estimated to have been lost in the third quarter of 2020, which is equivalent to 15 million full-time jobs.

- The 2.76% average annual increase in women’s labour force participation over the period 2000-20 was accompanied by an average 3.4% increase in the number of unemployed women. The region is not creating enough jobs to absorb the growth in the female labour force. Women’s economic participation in the region is clustered in public or quasi-public firms and in sectors that are deemed ‘female-friendly’, but they are largely under-represented in other formal private sector occupations.

The inequality challenge

Second, the formal private sector is characterised by high income inequality between capital owners and income earners, as indicated by a higher share of capital to revenues compared with the share of labour to revenues in the region’s formal private sector. This gap increases with firm size.

An increasing share of capital in production may eventually widen the inequality gap between capital owners and wage earners. Eventually, a large share of capital in production could also bias new technologies to augment capital and not labour.

The productivity challenge

Third, labour productivity of the formal private sector is comparable to other regions but has lower total factor productivity (TFP). Arab firms have a lower TFP in manufacturing compared with countries of similar income levels. They also have a comparable level of labour productivity owing to more capital intensity. SMEs have lower total factor productivity and shorter survival rates than large firms.

The technology challenge

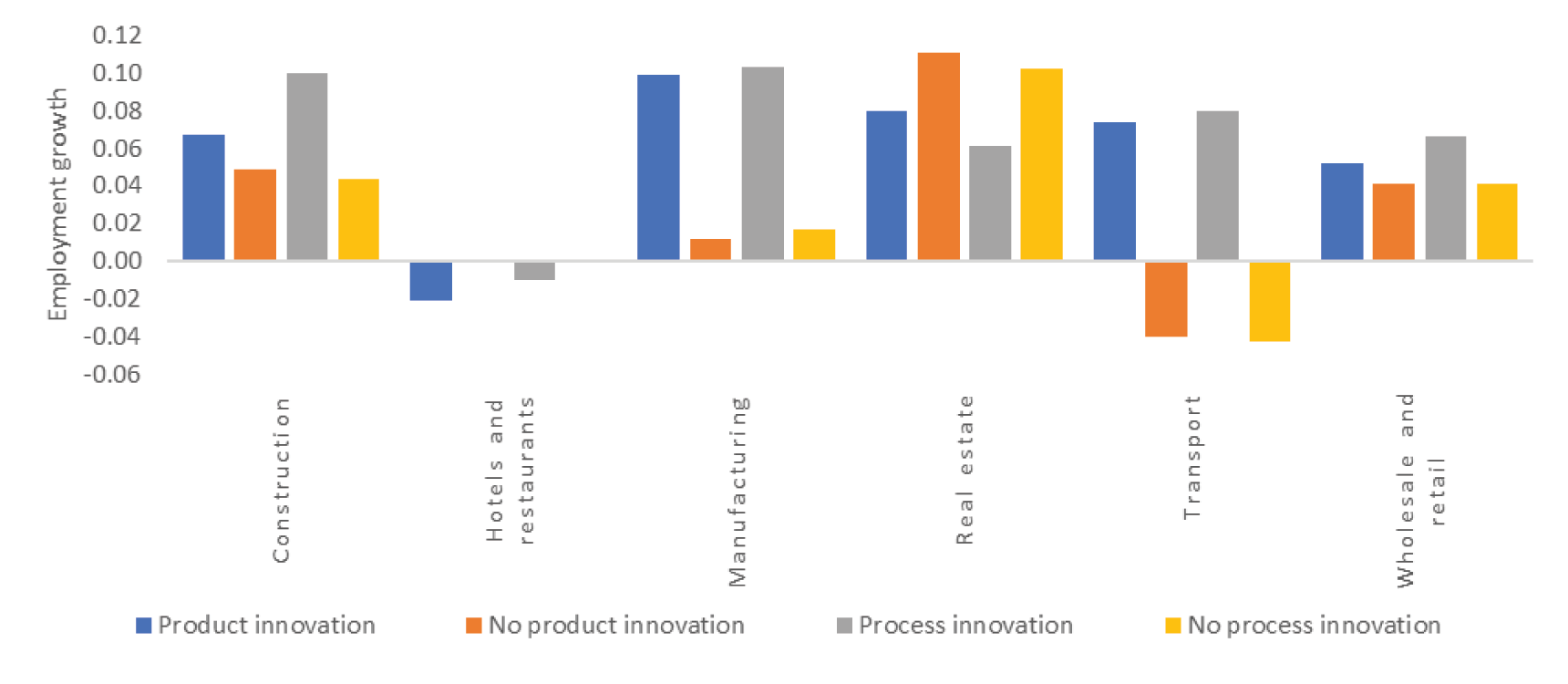

Fourth, the impact of innovation on employment creation in the Arab region is sector-dependent, with different types of innovations in various sectors affecting employment differently (see Figure 1).

In some sectors, any type of innovation could result in more employment creation, as it is the case in manufacturing, construction, transport, wholesale and retail. In other sectors, such as real estate, innovations that enhance production and increase the process efficiency reduce employment creation. Similar negative effects of innovation on employment have been witnessed in the hotel and restaurant sector.

Figure 1: Employment growth, by type of innovation

Source: ESCWA and ILO (2021) based on the World Bank Enterprise Survey datasets.

Note: The analysis is based on the most recent surveys.

Policy responses

There is no doubt that the weak regulatory framework in the Arab region, together with underdeveloped labour market institutions, inadequate fiscal space and the concentration of economic activity in low-productivity sectors, in addition to protracted conflict and political instability, have all contributed to these challenges and hence to the limited creation of decent formal jobs in Arab labour markets.

Coupled with low quality of education, these factors are seen as major obstacles and require integrated policy responses.

Proposed policy responses need to rise to the enormity of these challenges. They also need to take account of short-term interventions to address Covid-19, as well as medium and long-term solutions to structural problems. The report suggests the following ten areas for policy action:

Implement an immediate structured policy response to address the challenges resulting from the pandemic

It is necessary to stimulate the economy through more expansionary fiscal and monetary policies, including financial support to the most affected sectors. International and regional coordination, such as the ESCWA solidarity fund, remains vital for tackling pandemic challenges.

Develop proactive and comprehensive national employment policies

These policies are key to addressing structural, longstanding and multidimensional labour market challenges in Arab countries, including the inefficiencies of the private sector and its limited potential and capacity to create decent jobs.

Rethink macroeconomic policies that promote private sector development and encourage decent employment creation, productivity and inclusive growth

This includes designing effective fiscal policies and tools, re-emphasising the role of monetary policy in supporting private sector development, particularly SMEs, increasing fiscal inclusion, and designing and implementing pro-employment sectoral and industrial policies for improved diversification efforts.

Support the formalisation and expansion of social protection

Arab countries need to develop an integrated framework that addresses various decent work deficits, based on a proper assessment of their national contexts. Expanding social protection remains critical to providing adequate protection from rising poverty and vulnerability in the region and realising the fundamental human right to social security. The formalisation of enterprises should also be encouraged. But this should not be achieved through short-term job losses in the informal sector.

Improve women’s labour market prospects to promote gender equality and female empowerment

This requires challenging prevalent socio-cultural and discriminatory perceptions to promote women’s labour mobility and capitalise on their high level of education in all sectors. Furthermore, reforming labour laws to ensure a more gender-sensitive environment is a must. Downsizing public sector spending should not come at the cost of additional employment for women.

Reform educational programmes and develop effective active labour market policies, particularly for young people

Arab governments need to address the issue of skills mismatch through a holistic approach that also reforms the education system and curriculums. Investments in public employment services and active labour market policies also need to be boosted in the short run to ensure young people’s successful transition from school to work.

Offer additional incentives for private sector innovation, with a focus on labour-augmented technologies in production to complement employed capital and advance TFP

Spending on research and development should be scaled up to match global trends. Innovations also increase the productivity of capital and labour and enhance production competitiveness. At the same time, policy-makers should develop sound and fair income redistribution policies to reduce the gap between capital owners and income earners.

Develop sector-specific policies that tackle the negative impact of technology on employment and harness employment creation opportunities

Policy-makers in collaboration with firm owners should create reskilling and upskilling incentives for disadvantaged employees in sectors that could be negatively impacted by innovation, such as the real estate and hotel and restaurant sectors.

Rethink policies that provide incentives for SMEs to help them grow faster

This requires reviewing the overall private sector development atmosphere, enhancing digital transformation, reducing competition with the informal sector, increasing capacity-building, and enabling the required structural transformations in sectors where SMEs can grow and thrive.

Update labour laws and regulations, build a more skilled workforce and ensure a stronger and more competitive and innovative business environment

Additional employment creation requires revising labour regulations to support inclusiveness and fairness in the labour market and to accommodate more workers, including women.

Further reading

ESCWA and ILO (2021) Towards a Productive and Inclusive Path: Job Creation in the Arab Region.

ESCWA (2014) Arab Middle Class: Measurement and role in driving change.

ESCWA and ERF (2019) Rethinking Inequality in Arab Countries.

ILO (2020) ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the world of work, 4th edition.

ILO (2020) COVID-19: Labour Market Impact and Policy Response in the Arab States. Briefing Note with FAQs.

Sarangi, N, K Abu-Ismail and V Gantner (2017) ‘Fiscal policy and structural transformation in the Arab region: What are the pathways?’, ESCWA

United Nations (2017) Leave No One Behind: A Call to Action for Gender Equality and Women’s Economic Empowerment.