In a nutshell

Many economists and policy-makers see reforms of energy subsidies, specifically fuel subsidies, as ‘low-hanging fruit’; but even if accompanied by schemes to compensate consumers, such reforms are politically difficult.

To sustain needed reductions of greenhouse gas emissions while restoring citizen trust, authorities in MENA should use the region’s vast pool of renewable resources to accelerate the transformation of their energy systems and decarbonise transport.

Authorities must address longstanding issues pertaining to the economic governance of the energy sector and beyond that hamper the transformation of energy systems and their ability to reduce emissions systematically.

Economists have proposed carbon pricing to reduce the accumulation of greenhouse gas emissions that can remain in the atmosphere for centuries and destabilise the global climate (Rezai and van der Ploeg, 2014; van den Bremer and van der Ploeg, 2021). One approach to putting a price on carbon is to tax emissions based on the carbon content of the fossil fuels that produce them.

The policy debate has shifted from the need for carbon pricing to how to address its distributional implications – such as equity considerations and political feasibility (Klenert et al, 2018). The introduction of a gas tax in France is a case in point. The tax was a major cause of nationwide protests that lasted from late 2018 to the spring of 2021. The so-called yellow vest protests, which resulted in removal of the tax, are a stark reminder of the importance of distributional considerations and the need to garner popular support for bold climate policy action.

In the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, energy consumption is heavily subsidised, which has harmful environmental consequences. When energy is subsidised, the prices of energy products are well below those that would prevail under carbon pricing designed to account for environmental externalities.

Unsurprisingly, then, many economists and policy-makers see reform of energy subsidies, specifically fuel subsidies, as a ‘low-hanging fruit’ – both as a means to improving the environment as well as a way to create significant fiscal space (Coady et al, 2019).

Energy subsidy reforms, even if accompanied by schemes to compensate consumers, are politically difficult – especially in MENA, because of limited government legitimacy and citizen distrust of authorities. Moreover, reforms are often reversed after protests erupt.

Here, we argue for a new, holistic approach to reform to account for the frail social contract that has prevailed for decades between the political and economic elites and common citizens in most MENA countries.

To sustain needed emissions reductions while restoring citizen trust, authorities in MENA should use its vast pool of renewable resources to accelerate the transformation of their energy systems and decarbonise transport. Authorities must address longstanding issues pertaining to the economic governance of the energy sector but also complementarities between the energy sector and other sectors – such as finance and transport – that hamper the transformation of energy systems and their ability to reduce emissions systematically.

Energy subsidies, emissions and budget deficits

Energy consumption in MENA is heavily subsidised. These subsidies introduce a range of distortions – including wasteful consumption, misallocation and harmful effects on the environment from local air pollution and traffic congestion (Coady et al, 2019).

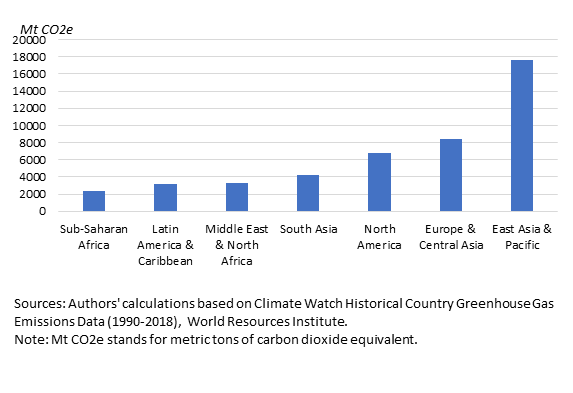

Overall, MENA produces 3,306 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (see Figure 1). That is slightly more than 7% of global emissions even though the region accounts for only 3.5% of global GDP. Saudi Arabia and Iran with respectively 638 and 828 metric tons of carbon dioxide are among the top ten emitters of emissions globally.

Figure 1: MENA greenhouse gas emissions in the world

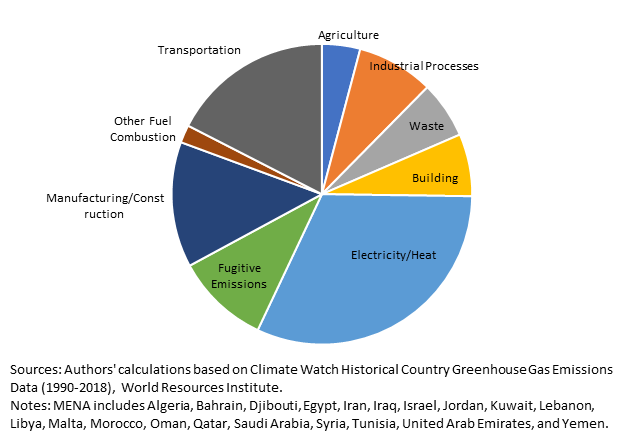

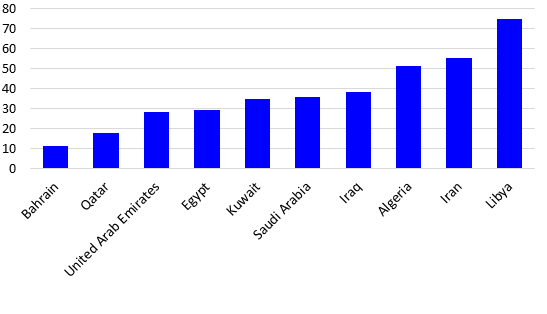

The electricity/heat and transport sectors are the most important sources of greenhouse gas emissions from MENA (see Figure 2). Subsidy rates for fuel, electricity, natural gas and coal are especially high – among the highest in the world (see Figure 3). A subsidy rate of say 10% implies that consumers paid on average around 90% of the competitive market prices for the subsidised energy products.

Figure 2: Sectoral decomposition of MENA greenhouse gas emissions

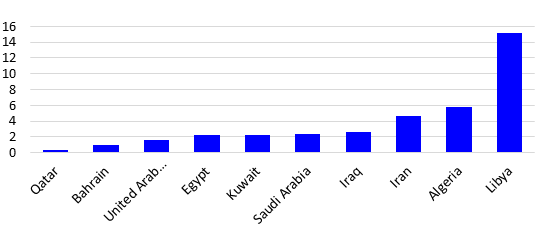

Rates can be higher than 50% in Algeria, Iran and Libya. In addition to environmental damages, energy subsidies entail a heavy drain on government budgets. The fiscal costs of subsidies in Iran, Algeria and Libya are between 4% and 15% of GDP (see Figure 4).

Figure 3: Average subsidisation rate in MENA (percent)

Source: International Energy Agency (IEA).

Notes: Data are as of 2020. Subsidies for fossil fuel consumption are measured using a price-gap approach. The approach compares average end-user prices paid by consumers with reference prices that correspond to the full cost of supply. The price gap is the amount by which an end-use price falls short of the reference price and its existence indicates the presence of a subsidy.

Figure 4: Total energy subsidies as a share of GDP (percent)

Source: International Energy Agency.

Notes: The chart shows total energy subsidies as a share of GDP as of 2020.

Political feasibility of energy subsidy reform

In principle, energy subsidies in MENA are a low-hanging fruit for climate policy action. But reforming them has proven difficult. Because the region has few functioning social welfare systems, subsidised energy prices are an important part of an inadequate social safety net (El-Katiri and Fattough, 2017).

Several oil-importing countries in the region have phased out fuel subsidies, but not without difficulties. In 2019, there were riots linked to energy in Lebanon, Iraq and Iran (see McCulloch et al, 2021) For the region’s oil- and gas-exporting countries, low domestic energy prices have also historically formed an important element of the social contract, in which political elites capture riches from the extraction of hydrocarbons and compensate citizens through a variety of direct and indirect channels, including energy subsidies.

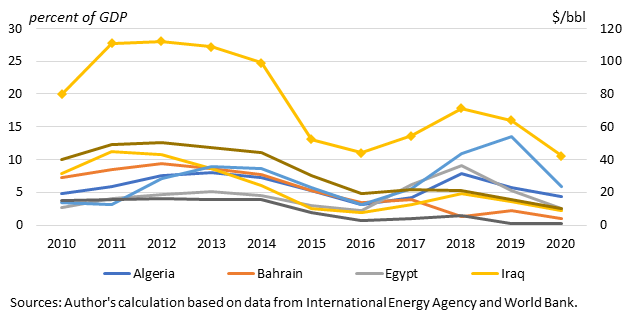

Figure 5: Fuel subsidy costs and oil prices

Notes: The top line shows crude oil price in US$ per barrel. Other lines show total fossil fuel subsidies as a share in GDP.

The period of persistently low oil prices that started in 2014 when oil prices collapsed has revived the drive to phase out energy subsidies in MENA. It should be politically easier to curtail subsidies when international fuel prices already are low because reforming domestic prices would lead to a much smaller price increase than when international prices are high.

When international fuel prices are low, reform should not only make curtailed subsidies more acceptable to consumers, it should also help to limit the fiscal cost of fuel subsidies when international fuel prices increase again (see Figure 5). Yet reforming energy subsidies in MENA is much more complex than relying on timing of fluctuations in international fuel prices. It involves a more holistic approach.

Still the urgent need for reforms after periods of delayed stabilisation in MENA has often impelled governments to focus on specific fiscal actions such as fuel subsidies, ignoring or oblivious to the wider consequences. While there is a strong rationale for moving away from universal consumer and producer subsidies because of how heavily subsidies affect the environment and budgets, attempts at reforms have caused protests, at times violent, even when measures were taken to mitigate the effect on the poor.

The rising aspirations of an overwhelmingly educated and young population in MENA contrast with the poor performance of governments in modernising their economies and creating jobs, and they provide another source of opposition to subsidy reform. That’s because of the distrust generated by the inability of governments in MENA to deliver quality and affordable public services and the (accurate) perception of official corruption that enables a crony-riddled private sector.

Social media amplifies the discontent (Arezki et al, 2020) by allowing citizens to react swiftly to missteps by often-secretive governments and permitting anti-government sentiments to spread easily.

It is the central role of subsidies in the unspoken social contract that is at the core of the opposition to subsidy reform. That social contract – in which citizens cede their voice and tolerate low government accountability in exchange for subsidies and public sector jobs – is already frayed among dissatisfied young people.

But that dissatisfaction has spread beyond youth as depleting budget coffers in many MENA countries impede delivery of adequate services to the broad population in such subsidised sectors as public transport.

For example, in many countries in MENA, private and mostly informal operators provide most transport services. These operators stepped in where the state failed to deliver and in many ways the fuel subsidy is a transfer-in-kind to compensate non-state operators for doing the state’s job. Removal of a fuel subsidy is perceived by the numerous small operators as a transfer from their pockets to those of a state that has done nothing to deserve it.

Distrust of government, then, is a big impediment to reforming energy subsidies, even when conditional cash transfers programmes compensate losers. According to the Arab Barometer, distrust in government in the region is high: 25% of the population has a positive view of government performance, while 84% believe there is corruption in state institutions, and only 41% believe the government is addressing the issue.

Consequently, it is not uncommon for subsidy reform efforts to be abandoned when governments are faced with street protests or if tensions build up when domestic energy prices increase. At present, countries are still battling the Covid-19 pandemic and few, if any, MENA countries have considered energy subsidy reforms to create fiscal space and none have acted.

Algeria, for example, approved a 9% cut in public spending in 2020, but kept subsidy policy unchanged to avoid social unrest (Reuters, 2020). Evidence from Indonesia and Nigeria indicates that perception of corruption in the implementation of targeted transfer programmes increases public resistance to fuel subsidy reform among the poor citizens who consume the least fuel and who stand to lose the most from any reductions in targeted programmes (see Kyle, 2018 and McCulloch et al, 2021).

Needed: a new approach to reform and transformation of energy systems

This resistance means a new approach to reform is needed to account for the dynamics of the constantly evolving social contract in MENA. Reform of consumer energy subsidies cannot be considered independent of the implicit producer subsidies – including those to inefficient state-owned enterprises – and the exclusive access many cronies have to public contracts.

The approach should articulate a broader vision of economic transformation in MENA aimed at creating a more genuine private sector that addresses economic woes both on the consumer and producer sides. Transformation, including energy systems and transport, should also be complemented by a more vibrant social protection system that cushions individuals from bad economic shocks and poverty.

Protection systems in MENA countries now are limited, inefficient and fragmented (Jawad et al, 2019). Well-designed and well-implemented systems not only will make energy reform more widely accepted, they can also encourage more individual risk-taking, fostering entrepreneurship and sustainable private sector development.

Because the inability of many MENA governments to deliver reliable basic services such as electricity and public transport, is at the heart of citizen distrust, it is essential that before embarking on subsidy reforms, authorities improve government performance and encourage competition in key sectors on which citizens depend.

Several economies in MENA are experiencing severe electricity crises. If development of reliable government services precedes subsidy reform, consumers would be more likely to accept the higher tariffs that would result from reduced subsidies – including the higher fares required to make MENA’s public transport more efficient and more environmentally friendly.

More broadly, if we are to meet climate goals, a large fraction of fossil fuel reserves is to be kept underground. MENA has the largest reserves of hydrocarbon in the world. McGlade and Ekins (2015) estimate that in the Middle East, reserves are three times larger than their ‘carbon budget’. In other words, 260 billion barrels of oil in the Middle East cannot be burned. In addition to stranded reserves, the structures and capital used in extraction and in exploitation of fossil fuel are at risk of also becoming stranded.

One implication of the potential stranded assets is that it could lead to a race to burn the last ton of carbon. That could in turn lead to the so-called green paradox whereby regulation aiming to limit carbon emissions ends up raising the latter at least in the short run (van der Ploeg, 2016).

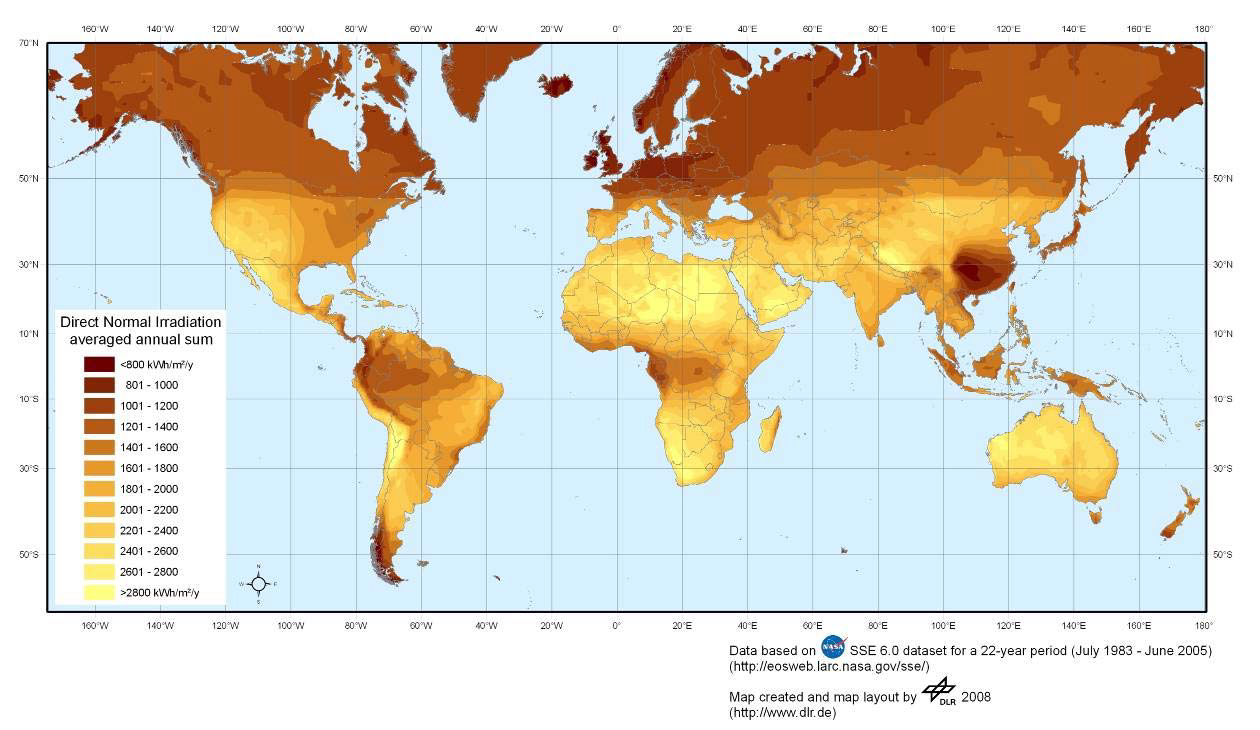

MENA has a huge potential in renewable energy generation that could substitute for subsidised fossil fuel consumption. According to the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration, solar radiation is highest in the region (see Figure 6). The technological changes driving the transition from fossil fuels to renewable sources present sizable economic opportunities for MENA, especially as the cost of renewables such as solar and wind are declining.

Authorities in MENA should tap the region’s vast pool of renewable resources to accelerate the transformation of their energy systems, which would have the doubly beneficial effect of reducing emissions while keeping energy costs from rising. In isolated and lagging regions, promoting decentralised energy systems could also help economically empower local communities.

The transformation of energy systems in MENA needs to be accelerated. Several economies are already investing heavily in renewables. Both the United Arab Emirates (UAE), an oil-exporting country, and Morocco, an oil importer, are engaged in ambitious efforts to develop renewable energy resources.

The UAE wants 30% of the energy used to produce electrical power to come from clean sources by 2030. Morocco, the host of the 2016 United Nations Conference on Climate Change, wants 52% of its installed generating capacity powered by renewables by 2030. The country has started to build a massive solar power plant in the Sahara desert that is expected to have a capacity of two gigawatts, which would make it the world’s largest solar power production facility.

Figure 6. Potential for solar energy

Sources: US National Aeronautics and Space Administration; and The Institute of Engineering Thermodynamics at the German Aerospace Center.

Notes: The chart shows averaged annual sum of the direct normal irradiation around the world.

Overall, installation of new renewable capacity in MENA lags the rest of the world, although growth in the region’s use of renewable energy is among the fastest in the world, mainly off a small base (IRENA, 2020). In a world in which renewables accounted for at least 70% of total capacity expansion in 2019, renewables accounted for only 26% of net additions in the Middle East.

Transformation in MENA energy systems will require large investment. Luckily there is a growing interest in climate friendly investments in the global financial community. To tap into that interest, MENA economies must tackle longstanding issues that constrain the ability of their energy systems to absorb investment (Arezki, 2021).

Sovereign borrowing cannot be the exclusive driver of climate friendly investment. The private sector, both domestic and foreign, should also be a conduit of climate finance for the continent. Traditionally, high financing costs and tights caps that preclude companies from adjusting tariffs to cover those costs make it difficult to develop bankable purchasing power agreements.

Developing decarbonised transport assets – including railways and other mass transit options – will also help to reduce emissions, ensure energy demand predictability and stimulate investment in the electricity sector.

It won’t be easy. There are problems related to the economic governance of the energy sector, but also complementarities between the energy sector and other sectors that hamper the ability of MENA economies to absorb investment. In turn, these problems discourage the global investor community.

But if authorities can force the right changes, MENA economies – especially those with little available capital – will be able to tap into the growing interest of global investors in making climate friendly investments in a socially acceptable manner. And a beneficial side effect would be that the investments would help fix the increasingly onerous and unreliable access to energy and other public services that have exacerbated social tensions.

This is a shortened version of ‘Reforming Energy Subsidies in the Middle East and North Africa: Easy Pickings for Climate Policy or a Political Bombshell?’ by Rabah Arezki, Rachel Yuting Fan, Ha Nguyen, a chapter in the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) ebook No Brainers and Low-hanging Fruit in National Climate Policy: Country-specific insights for implementing achievable and efficient climate change policies.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the African Development Bank and the World Bank.

Further reading

Arezki, Rabah (2021) ‘Climate Finance for Africa in the XXI Century’, mimeo, African Development Bank.

Arezki, Rabah, Alou Adesse Dama, Simeon Djankov and Ha Minh Nguyen (2020) ‘Contagious Protests’, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series No. 9321.

van den Bremer, Ton S, and Frederick van der Ploeg (2021) ’The Risk-Adjusted Carbon Price’, American Economic Review 111(9): 2782-2810.

Coady, David, Ian Parry, Nghia-Piotr Le and Baoping Shang (2019) ‘Global Fossil Fuel Subsidies Remain Large: An Update Based on Country-Level Estimates’, IMF Working Paper, May 2019: Issue 089.

El-Katiri, Laura, and Bassam Fattouh (2017) ‘A Brief Political Economy of Energy Subsidies in the Middle East and North Africa’, in Giacomo Luciani (ed.) Combining Economic and Political Development: The Experience of MENA.

International Energy Agency (2019) World Energy Outlook.

International Renewable Energy Agency (2020) ‘Renewable Capacity Highlights 2020’.

Jawad, Rana, Nicola Jones and Mahmood Messkoub (2019) ‘The New Social Protection Paradigm and Universal Coverage’, Elgar.

Klenert, David , Linus Mattauch, Emmanuel Combet, Ottmar Edenhofer, Cameron Hepburn, Ryan Rafaty and Nicholas Stern (2018) ‘Making carbon pricing work for citizens’, Nature Climate Change 8 669-77.

Kyle, Jordan (2018) ‘Local corruption and popular support for fuel subsidy reform in Indonesia’, Comparative Political Studies 51(11): 1472-1503.

McCulloch Neil, Davide Natalini, Naomi Hossain and Patricia Justino (2021) ‘An exploration of the association between fuel subsidies and fuel riots’, Research Square.

McCulloch, Neil, Tom Moerenhout and Joonseok Yang (2021) ‘Fuel subsidy reform and the social contract in Nigeria: A micro-economic analysis’, Energy Policy 156: 112336.

McGlade, CE, and P Ekins (2015) ‘The Geographical Distribution of Fossil Fuel Unused when Limiting Global Warming to 2oC’, Nature 517: 187-90.

Rezai, Armon, and Frederick van der Ploeg (2014) ‘Intergenerational Inequality Aversion, Growth and the Role of Damages: Occam’s Rule for the Global Carbon Tax‘, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 10292.

Reuters (2020) ‘Algeria faces ‘unprecedented’ multi-dimensional crisis: PM’, 10 March 2020

van der Ploeg, Frederick (2016) ‘Fossil fuel producers under threat’, Oxford Review of Economic Policy 32(2): 206-22.