In a nutshell

Spillover effects on growth arising from bilateral trade linkages within the MENA region are limited to just a few countries – the large and/or oil-producing economies of Saudi Arabia, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates.

China has far more powerful effects on MENA growth through its trade partners in the region: a 1% increase in the trade balance as a share of GDP in China is associated with 0.4145% increase in GDP growth for the MENA region.

That the region does not benefit from its own growth spillovers through trade is an issue that MENA policy-makers should examine in their future deliberations.

To what extent does economic growth in one country in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region ‘spill over’ to boost growth in others? In recent research, we postulate that such spatial effects of growth in MENA countries may arise on the basis of geography, bilateral trade or institutional similarities (Baysoy and Altug, 2021).

We find evidence for spatial dependence among the MENA countries. We also show that the spillover effects of growth are due to economic activities in countries that trade primarily in oil. Considering the role of trade, we show that the spillover effects on growth arising from bilateral trade linkages are limited to just a few countries – Saudi Arabia, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates – which is not enough for the emergence of substantial growth spillovers within the region.

Here, we extend our analysis to include China as one of the countries through which spatial growth effects may arise in the region. Incorporating the China in an analysis of growth spillovers seems especially relevant, as the country has emerged as a major trading partner for both developed and developing regions of the world in recent decades.

For over a millennium, China maintained its position as a world trading power through the Silk Route, which was a vast trading network with north, central and south sea-faring routes (Çınar et al, 2015). The country’s new Belt and Road Initiative seeks to recreate the ancient Silk Road through infrastructure projects encompassing 60% of the world’s population (across 65 countries) and 30% of global GDP. Hence, understanding China’s role in creating potential growth spillovers for the MENA region seems a key issue.

There are a few studies that have sought to understand the nature of spillovers for the MENA region. In contrast to our approach, they focus on the cyclical response to foreign shocks as the source of regional spillovers.

Hanson et al (2018) find that trade and financial flows between MENA countries are modest. They also find that increased trade ties between China and other large emerging economies have led to an increase in growth spillovers from the largest emerging market economies to the developing MENA region. They conclude that ‘on average, growth spillovers from China to developing MENA are as big as those from the Euro Area (EA), and in some cases even higher.’

Cashin et al (2012) study the spillover effects from macroeconomic shocks in systemic economies (China, the Euro Area and the United States) to the MENA region. They show that the MENA countries are more sensitive to developments in China than to shocks in the Euro Area or the United States, in line with the direction of evolving trade patterns and the emergence of China as a key driver of the global economy.

Our analysis captures the spatial dependence that arises when a country’s growth depends on its neighbour’s growth. We consider a trade-weighting matrix based on bilateral trade linkages for China and 18 MENA countries: United Arab Emirates (ARE), Bahrain (BHR), Djibouti (DJI), Algeria (DZA), Egypt (EGY), Islamic Republic of Iran (IRN), Iraq (IRQ), Israel (ISR), Jordan (JOR), Kuwait (KWT), Lebanon (LBN), Morocco (MAR), Malta (MLT), Oman (OMN), Qatar (QAT), Saudi Arabia (SAU), Tunisia (TUN) and Turkey (TUR).

We use a panel of nine periods based on five-year averages of real GDP growth rates. Our results show that part of the growth of each country is through the spatial effect of neighbouring countries’ growth. Specifically, we find that a 1% increase in the weighted average of neighbouring countries’ growth rates increases a MENA country’s domestic growth by 0.26%.

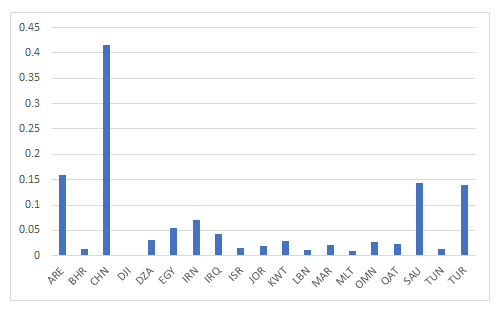

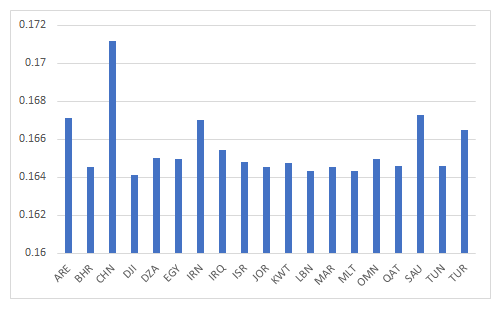

Figure 1: Indirect and direct effects of the trade balance on GDP growth

Indirect effects

Direct effects

We also examine how a change in a given explanatory variable in one country can affect the growth of all other countries, accounting for the spillover effects in growth. This is known as indirect effect deriving from a change in a given explanatory variable. Likewise, the direct effect of a given explanatory variable in one country arises from the feedback effects of other individual countries’ growth on its own growth.

The indirect and direct effects of a change in the trade balance are shown in Figure 1. China has by far the largest indirect and direct effects, followed by the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and Turkey.

The three MENA countries are also the largest economies in the region with respect to their real GDP. But the indirect effects of the trade balance variable due to China are nearly three times greater than the indirect effects due to the three MENA countries.

In Baysoy and Altug (2021), we noted that institutions in the MENA region have been built around the production and sale of a relatively homogeneous good – oil – which is sold on organised exchanges and does not require complex forms of contracting.

Hence, the comparative advantage associated with trade in goods that require more complex forms of contracting institutions is not captured by MENA countries, which rely on the growth effects that oil-rich countries create for oil-poor ones in the region based on such factors as remittances, aid and investment flows (Luciani, 2017).

There may be other reasons that limit the scope for trade in the MENA region such as the lack of trade liberalisation and restrictive trade practices.

But the salient finding from Figure 1 is the absolute dominance of China’s growth in generating spillover effects for the region. Hanson et al (2018) argue that while spillovers from China for the MENA region as a whole are small, there may be third-party effects from China spillovers. These occur as China affects the largest economies in the MENA region, such as Turkey, which in turn can affect other countries that are not directly affected by China.

Cashin et al (2012) make a similar point by noting that even if countries do not trade as much with a systemic country like China, they may be influenced by its dominance through other partners’ trade. Their study considers trade weights averaged over the periods 1986-88 and 2006-08 separately.

They find that that ‘20 years ago, a negative Chinese output shock would not have had a statistically significant effect on either the systemic economies, major oil exporters, or the MENA region…’ By contrast, not only does ‘a [current] Chinese GDP shock affect the global economy in a much more prominent way, but the median effects are generally much larger than two decades ago’.

In our case, we consider bilateral trade weights averaged over the period 2010-12 and find that a 1% increase in the trade balance as a share of GDP in China is associated with 0.4145% increase in GDP growth for the MENA region.

We conclude our analysis by noting that growth spillovers from trade in the MENA region appear to arise from two distinct phenomena: one is through the activities of the largest economies in the region, which include the oil-producing countries together with Turkey; while the second is through the dominance that China exerts through its trade partners in the region.

That the region does not benefit from its own growth spillovers through trade is an issue that policy-makers in the region should examine in their future deliberations.

Further reading

Baysoy, MA, and S Altug (2021) ‘Growth Spillovers for the MENA Region: Geography, Institutions, or Trade?’, The Developing Economies 59: 275-305.

Cashin, P, K Mohaddes and M Raissi (2012) ‘The Global Impact of the Systemic Economies and MENA Business Cycles’, International Monetary Fund Working Paper 12/255.

Cinar, EM, K Geusz and J Johnson (2015) ‘Historical Perspectives on Trade and Risk on the Silk Road, Middle East and China’, in Topics in Middle Eastern and African Economies: Proceedings of the Middle East Economic Association.

Hanson, J, R Huidrom and E Islamaj (2018 ‘Growth Spillovers to Developing MENA’, manuscript, International Monetary Fund.

Luciani, G (2017) ‘Oil Rent and Regional Economic Development in MENA’, in Combining Economic and Political Development: The Experience of MENA, International Development Policy series 7, Graduate Institute Publications: 211-30.