In a nutshell

Following the establishment of the Kurdistan region of Iraq, aid was initially used solely for humanitarian purposes; later, the Kurdistan regional government (KRG) was awarded grants to improve governance, investment in human capital and growth.

After the establishment of the KRG in 1992, three factors have contributed largely in the development of the KRI: international aid; the region’s share in the Iraqi budget allocation; and the relative security of the region compared with other devastated parts of Iraq.

Aid would be more effective if the KRG was involved in policy and institutional reforms associated with it.

Research on aid and development typically identifies two types of aid: humanitarian aid and development assistance (Collier, 2013).

Humanitarian aid is short-term material and logistical assistance to people who need help. It is a key part of the contemporary toolkit of peace-building and post-conflict reconstruction (Narang, 2015). While global humanitarian aid increased after the end of the Cold War – from $796 million in 1989 to $11 billion in 2008 – more recently, it has decreased – from $31.2 billion in 2012 to $29.6 billion in 2019 (Narang, 2015; Global Humanitarian Assistance Report, 2020).

The aim of development assistance is to accelerate long-term growth. Collier (2013) discusses how aid can support growth in small economies that are integrating into the global economy. Aid for development assistance has been viewed as a form of unearned government income that is affected by the capacity of the recipient government, the quality of its institutions as well as the structure of the economy.

In systematic empirical work on how policy and aid affect economic performance, Collier and Hoeffler (2002) measure economic performance of aid-recipient countries as a function of aid and policy, using international data for the period from 1973 to 1997. They find that the effectiveness of aid relies on policy, with faster growth associated with better policy.

Foreign aid is often seen as increasing incentives for civil war. But when aid is used to finance development, it may reduce the risk of conflict. Using global data for the period from 1965 to 19999, Collier and Hoeffler (2002) investigate the relationship between aid and conflict. Their findings show that both economic performance and economic structure have powerful effects on the risk of conflict in aid-recipient countries: aid reduces the incidence of civil war by fostering economic growth and strengthening states’ capabilities.

Aid has been aimed at strengthening the functional capacity of institutions to provide security, education, health, transport and other core public services. The rationale of development aid policy for institution and state-building is that improving the governance capacity of recipient countries will affect the quality of institutions and thereby support the competitiveness of markets (Sahin and Shahin, 2020).

But aid for development assistance does not always motivate reforms and state-building, but can hinder institutional change in recipient countries. The effects of international aid on the rule of law in developing countries show that aid cannot buy law. While billion dollars of aid has been spent in promoting the rule of law in developing countries, little improvement has been made. According to Erbeznik (2011), this is because aid has been spent in supporting institutions through informal political or cultural norms rather than spending it on reform in formal rule of law institution.

Since the establishment of the Kurdistan region of Iraq (KRI) in 1992, international aid has played an important role in development of the region. While at the beginning, aid was used solely for humanitarian purposes, later the Kurdistan regional government (KRG) was awarded grants to improve governance, investment in human capital and economic growth.

After the establishment of the KRG in 1992, three factors have contributed largely in the development of the KRI as a post-conflict area between 1992 and 2012: international aid from donors; the share of the KRI in the Iraqi budget allocation; and the relative security that the region has had compared with other devastated parts of Iraq.

Pre-conflict aid and its consequences in the KRI

During the decade of Kurdish de facto autonomy (1991-2003), aid was limited to humanitarian purposes carried out by the UN and NGOs, which always played a significant role in the recognition of the region. The UN and international agencies’ intervention in the creation of a secure region and humanitarian participation helped further expansion of the narrow framework of Kurdish aspiration from dream to de facto.

Thus, the establishment of the KRG in 1992 partly resulted from the advantage of this international protection from creating a relatively secure region and aiding them. The formation of a safe haven no-fly zone in the Kurdish habitat (Northern Iraq) by United Nations Security Council (UNSC) Resolution No.688 approved on 5 April 1991 was the cornerstone for what is now the autonomous KRI.

According to Natali (2010), external aid to the region provided the international recognition and internal sovereignty necessary for their emergence and survival, and then offered quasi-state opportunities for them. But aid in the form of food and fuel handouts increased the heavy dependency of the KRG on the international agencies. Living standards during that time became worse, since the region had not been formally assisted by the Iraqi government, and the Kurdish civil war tore the region apart, creating large economic and political problems.

Post-conflict aid and its consequences

After the 2003 war, almost all areas of Iraq required reconstruction and this largely fell under the US responsibility. The United States has searched for foreign support in the form of pecuniary resources and manpower to rebuild the destroyed country. Such a process represented the most far-reaching reconstruction efforts since the Second World War when Europe and Japan were undergoing restoration (KRG-MOP, 2009).

The general purpose of aid in Iraq was towards rehabilitation of physical infrastructure and to affect government fiscal behaviour. Over $20 billion was committed for funding infrastructure projects from 23 donors; while in the KRI, around $1.2 billion has been committed from 12 donors (KRG-MOP, 2012). The application of the programme in the KRI was built on Iraq’s strategy, whilst the distributional effects of aid in Kurdistan have been used to strengthen its fiscal semi-independence.

The KRG has been awarded grants to improve governance, reasonable economic growth and investment in human capital, which eventually, with a large budget, would achieve high rate of economic growth. This contribution included the multiplicity of projects that have effectively been involved in the development of the region, which provided 1,954 grant assistance projects from 12 donors.

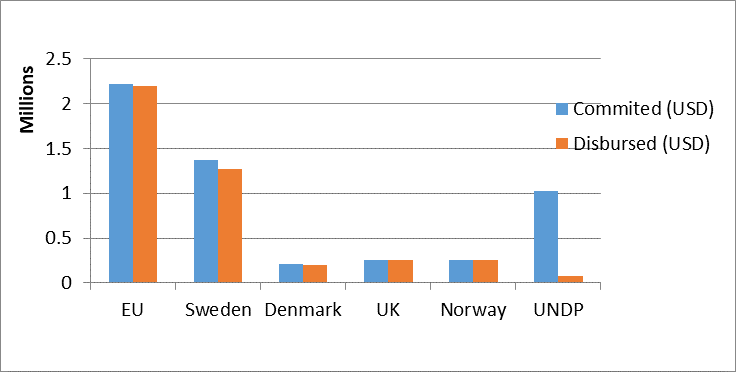

Those donors included UN agencies, international financial institutions and international and national NGOs (see Figures 1a and 1b). The KRG established a coordinated unit to monitor the quality and quantity of expense of foreign resources with strategies and policies aimed at avoiding waste of valuable development sources (KRG-MOP, 2009).

Data Source: ERMU (2012)

While there was a large difference in the number of projects between the region and the rest of Iraq, the diversity of the projects has awarded a real contribution of aid in the socio-economic development of Kurdistan. Generally, the implementation of aid projects in Iraq was around 20,000, of which only approximately 10% was allocated to the KRI.

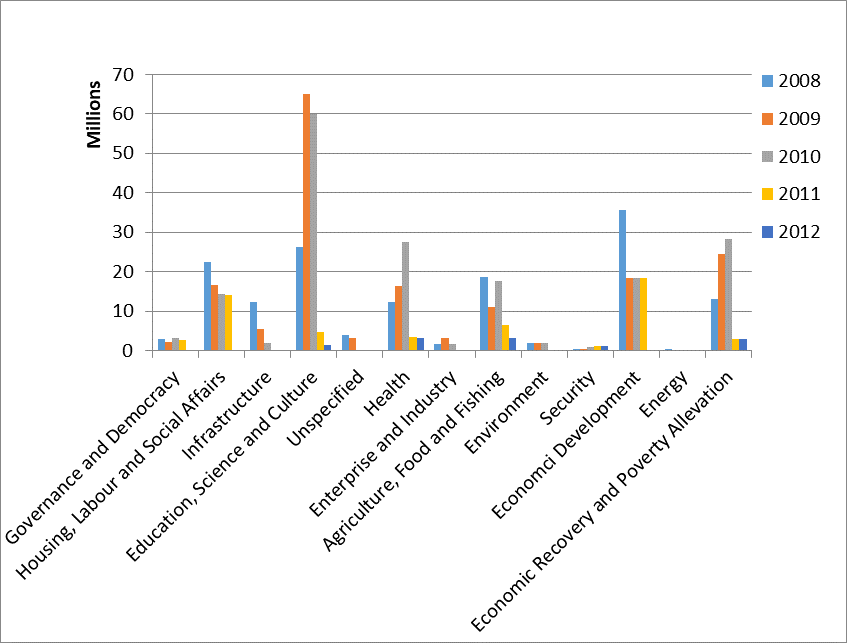

This indicates that it was not taken into consideration that the region was the most neglected area in Iraq in Saddam Hussein’s era; but also that it was given less than the national revenue-sharing agreement. Nonetheless, the manifest multiplicity of projects together with the national budget have provided a holistic atmosphere of development in the region – see Figures 2a and 2b.

Data Sources: ERMU (2012)

After the first election in 2005 in Iraq, a transient improvement in security took place: although Iraq was not completely peaceful, the funded projects were then directed towards rehabilitation of the country. Later, as security and political progress plummeted, donors appear progressively concerned with Iraq’s ability to maintain security.

It was diagnosed that post-conflict settings necessitate certain forces to maintain order and justice, and then to make a safe region for its activity. It seems nevertheless that aid conditionality continues to assure the territorial integrity of Iraq (Natali, 2010). Therefore, the secure situation of the KRI was not taken into account to fund projects other than security.

It seems that partial development of the KRI has resulted from substantial inflows of money, of which the United States appears to be the major contributor. While there appears to be a considerable gap between the KRI and other parts of Iraq regarding the number of the projects as well as amount of allocated aid, the magnitude of the share remains large.

Security was by far the largest sector, which has been co-funded by most of the donors, accounting for 48%. Nonetheless, it appears that the situation of KRI has not been taken into consideration regarding the fact that it has been the safest part of Iraq, resulting in exclusion of the KRG from the decision-making process, which affected its regional policies. Despite the fact that aid resulted in the development of the region, it increases the dependence of the KRG on the federal government of Iraq and other donors.

Conclusion and policy recommendations

Aid has contributed to rebuilding Iraq’s infrastructure, including the development of the KRI. Despite the fact that previous Kurdish autonomy between 1991 and 2003 received humanitarian funds, the region does not, in fact, have a long relationship with aid. Foreign aid has benefited the region, supporting substantial improvements in its economy.

In post-conflict times, the KRI has been in desperate need of foreign aid to start its journey towards building the most basic state institutions, security, infrastructure and economic growth. Foreign aid has recorded significant success in development of the region.

The KRG needs to be involved in directing aid for development in ways that contribute to growth and development. Aid would be more effective if the KRG was involved in policy and institutional reforms associated with it.

Further reading

Collier, P (2013) ‘Aid as a catalyst for pioneer investment’, WIDER Working Paper No. 2013/004.

Collier, P, and A Hoeffler (2002) ‘Aid Policy and Peace: Reducing the Risk of Civil Conflict’, Defence and Peace Economics 13(6): 435-50

Erbeznik, K (2011) ‘Money Can’t Buy You Law: The Effects of Foreign Aid on the Rule of Law in Developing Countries’, Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies 18(2): 873-900.

ERMU (2012) Data on Donor Contribution to the Kurdistan Region, 2003-2012, KRG Ministry of Planning, External Resources Management Unit.

Global Humanitarian Assistance Report (2020) development initiatives.

KRG-MOP (2009) Report on Donor Contributions to the Kurdistan Region. Kurdistan Regional Government, Ministry of Planning.

KRG-MOP (2012) Report on Donor Contributions to the Kurdistan Region, Kurdistan Regional Government, Ministry of Planning.

Narang, N (2015) ‘Assisting Uncertainty: How Humanitarian Aid Can Inadvertently Prolong Civil War’, International Studies Quarterly 59: 184-95

Natali, D (2010) The Kurdish Quasi-State, Development and Dependency in Post-Gulf War Iraq, Syracuse, New York.

Sahin, SB, and E Shahin (2020) ‘Aid‐Supported Governance Reforms in Solomon Islands: Piecemeal Progress or Persistent Stalemate?’, Development Policy Review 38(3): 366-86.