In a nutshell

Good institutions can chart a path to recovery: investing in testing, disease surveillance and data transparency can reduce the economic costs of the pandemic.

As the pandemic subsides, effective and transparent pandemic surveillance in the region would help boost demand from domestic and foreign sources.

Good governance in public investment decisions can raise the economic gains of public investment projects.

More than a year after the World Health Organization declared the Covid-19 outbreak a public health emergency of international concern, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region remains in crisis. Taking stock of the pandemic’s economic toll makes for grim reading. In MENA, the pandemic triggered multiple shocks that overlaid long-standing and structural development challenges.

In 2020, the region’s real output contracted by 3.8%. The rebound expected in 2021 is unlikely to be sufficient to return the region’s economic activity to the 2019 level, let alone the 2021 level that the World Bank projected before the pandemic. By the end of 2021, the region’s GDP per-capita will be 5% below its 2019 level and 7% below where it was predicted to be pre-pandemic.

Debt is a critical tool for many governments to deal with the pandemic

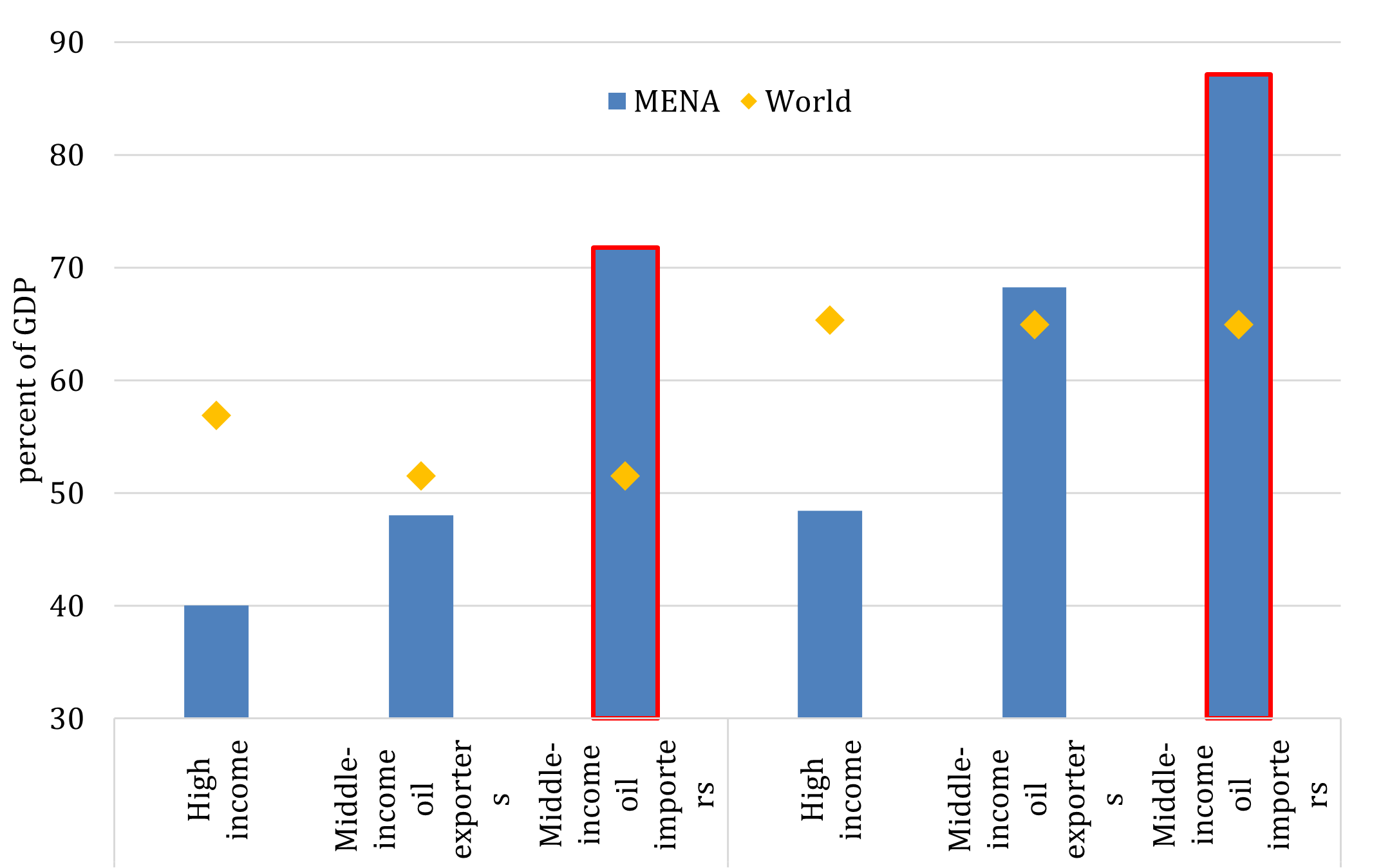

The disaster relief demanded by the pandemic, combined with a decline in fiscal revenues, led to accelerated accumulation of debt in a region already burdened with high public debt. The World Bank expects the region’s public debt to rise from 46% of its GDP in 2019 to 54% by the end of 2021. This increase would be MENA’s fastest accumulation of public debt as a share of output in the 21st century.

The increases are observed across MENA country groups (see Figure 1). The group of MENA oil importers entered the pandemic with already elevated public debt. By the end of 2021, their debt will be about 93% of GDP in 2021.

Figure 1: Median public debt by country group

Source: World Bank, Macro and Poverty Outlook (April 2021)

Note: Country groups are represented by median observation of the group. The bars show median debt of MENA country groups. The diamonds show median debt of the corresponding world’s income groups. Debt data are generally not available for MENA low income (Yemen and Syria). The high-income group in MPO is limited to only countries covered by the World Bank.

The knowledge gained from studies of natural disasters can help to understand the benefits of debt-financed recovery for the pandemic, an analogous disaster. In a sample of 90 developing countries between 1960 and 2019, evidence shows that growth in both public debt and output tends to rise faster after disasters than it does in economies without disasters, thus illustrating how debt-financed fiscal expansions can help economic reconstruction.

But debt is a double-edged sword

As the pandemic subsides, tensions will inevitably arise between potential short-run gains and long-run costs. In the longer run, high debt might bring economic risks and costs, especially for developing economies. Private sector investment may be crowded out as rising interest rates increase the cost of capital. Costly debt interest payments may gradually reduce the space for growth-enhancing public investments.

Excessive debt could also increase macroeconomic risks, reduce creditworthiness and affect the ability of economies to refinance (or roll over) maturing debt in the future. These risks, if they materialise, can result in such economic ailments as currency devaluations, runaway inflation, capital flight and costly debt crises.

In our report (Gatti et al, 2021), we delineate these trends and detail the evidence. Furthermore, we bring the best evidence to bear and reckon with the trade-offs in plotting a path forward for debt and fiscal policy in the region.

The key message is that transparent institutions can help to chart a path to long-lasting recovery across the three phases of the pandemic: during the pandemic, as the pandemic subsides and post-pandemic.

Prioritising spending during the pandemic

In the middle of the pandemic, one can think of fiscal spending as disaster relief, with resources best allocated to protect the welfare of vulnerable families and to strengthen public health. Supporting the consumption of the hardest hit households is an essential objective for governments in the region. MENA countries have taken unprecedented actions to support the most vulnerable.

The good news is that cash transfers are reasonably well targeted. Evidence from telephone surveys in the region suggests bigger portions of the poorest households are beneficiaries than of those at the top of the income distribution. Yet there is room to improve because social transfers have been able to reach only a small portion of the most needy families.

Better data and updated social registries with broad population coverage can help to target this spending effectively and rapidly. Ramped up investment in testing, disease surveillance and timely communication about Covid-19 spread can help to target government action and citizens’ decision.

Finally, a rapid rollout of vaccines would not only save lives, but also reduce the risk of a prolonged crisis and speed up economic recovery while reinforcing the infrastructure for long-term public health, something that is much needed. Rough calculations indicate that the benefit-cost ratio could be large, around 78:1, if MENA countries vaccinate 20% of their population at the prices currently proposed by COVAX, the multilateral effort to channel Covid-19 vaccines to poor and lower-middle-income countries.

Fiscal stimulus as the pandemic subsides

MENA countries must decide whether additional fiscal stimulus is warranted after the public health emergency abates. There are good reasons to be cautious, especially for many MENA countries with high debt, poor governance and lack of transparency.

First, fiscal stimulus may not be necessary. Economic growth might rebound without fiscal stimulus. Consumer and business spending might rise quickly after health risks have subsided – the result of demand that was pent-up during the pandemic. But whether pent-up demand emerges may be determined by the effectiveness and transparency of governments’ pandemic surveillance, especially for economies dependent on tourism.

Second, fiscal stimulus may be ineffective in countries with high debt. Evidence suggests that the so-called fiscal multiplier – the effect on GDP from additional spending – can be zero if public debt is high. Therefore, thoughtful consolidation could be a preferred policy stance in economies with very high public debt ratios.

Third, public investment may have limited effects when governance is poor because lack of transparency can interfere with the selection of investment projects that have the highest social returns.

But targeted fiscal spending can continue to help, especially to address the potential long-lasting scarring that the pandemic crisis is generating. For example, spending that provides subsidised loans and job training could alleviate financial constraints that might prevent re-entry of firms into the market and help workers who are unemployed or under-employed due to the crisis.

Similarly, investment in education can help disadvantaged children recoup learning lost during the pandemic and avert costly long-term losses in human capital.

Mitigating the costs of debt after the pandemic

Ultimately, economic growth is the most sustainable way to reduce public debt, but it is easier said than done, given the limited success of needed reforms that have been encouraged for decades in the region. Institutional reforms entail limited fiscal costs and this crisis could be the ideal opportunity to bring together the needed political willpower to make them happen.

Investments in the capacity of the health sector, increased use of data and digital connectivity due to the pandemic could provide a platform on which to build. Institutions might be the pathway to helping MENA countries build back better, with or without short-term fiscal consolidation.

Highly indebted MENA countries can prioritise the most effective spending items and improve governance surrounding spending decisions. This could improve the effectiveness of fiscal spending and permit a reversal of rising debt trends. Thoughtful fiscal consolidation would be welcomed by the private sector. MENA countries can roll over debt on more favourable terms by enhancing their long-term growth prospects. Transparency could also help reduce the cost of debt rollover by improving debt reporting and monitoring of financial market vulnerabilities.

If rolling over debt is not an option, costly debt restructurings might be on the menu. The evidence shows that pre-emptive restructurings, where external debt is restructured before payments become delinquent, are less costly than post-default restructurings.

Unfortunately, the evidence presented in our report also suggests that highly indebted countries are more likely to enter either pre-emptive or post-default restructurings with low growth and weak governance. Several MENA countries exhibited low growth and weak governance relative to world peers before the pandemic.

Good institutions can chart a path to recovery

Improvements in governance and transparency help during the pandemic and when it subsides. Investing in testing, disease surveillance and data transparency can reduce the economic costs of the pandemic.

As the pandemic subsides, effective and transparent pandemic surveillance in the region would help boost demand from domestic and foreign sources – such as the arrival of foreign tourists. Good governance in public investment decisions can raise the economic gains of public investment projects.

Finally, institutional reforms to improve governance and transparency can address the trade-off between the short-term needs and long-term costs of public debt. They can be implemented with limited fiscal costs. They also hold the promise of boosting long-run growth. Institutions might be the key to helping MENA build back better, with or without fiscal consolidation.

Further reading

Gatti, Roberta, Daniel Lederman, Ha Nguyen, Sultan Abdulaziz Alturki, Rachel Yuting Fan, Asif Islam and Claudio Rojas (2021) Living with Debt: How Institutions Can Chart a Path to Recovery in Middle East and North Africa, MENA Economic Update, April 2021, World Bank.