In a nutshell

The region’s public sectors are generally larger and much more male than average; but there are also substantial differences in the size and composition of public sectors within the region.

Public sector employment represents close to 26% of total employment on average for the seven MENA states in the Worldwide Bureaucracy Indicators database, 11 percentage points higher than the average rate for 108 non-MENA states.

There does not seem to be an urban bias in the make-up of public sector employees: evidence for Tunisia, Palestine and Egypt indicates near symmetry in the rates of paid public and private sector employment among rural residents.

The public sector is central to contemporary accounts of the political economy of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Scholars blame MENA states’ sprawling public sectors for the region’s weak private sector, limited economic integration (Malik and Awadallah, 2013) and entrenched authoritarian regimes (Desai et al, 2009).

But to what extent are the levels and characteristics of public sector employment in MENA states unique to the region? Comparing patterns of public sector employment within and beyond MENA can help test and nuance prevailing arguments on the political and economic consequences of MENA states’ public sectors.

The World Bank’s Worldwide Bureaucracy Indicators (WWBI) database offers an exciting opportunity to do so. The WWBI compiles over 400 household surveys from 115 countries from 2000 to 2016. In addition to estimating levels of public sector employment, the WWBI provides demographic characteristics of public sector employees (age, gender, education, rural/urban) and wage differentials with the private sector. This database contributes to the World Bank’s Bureaucracy Lab, which strives to use data to advance effective civil service reform.

Inspired by Pamela Jakiela at the Center for Global Development and Jennifer Guay at Apolitical, here are three observations on public sector employment in MENA from the WWBI database. Alas, only seven MENA states are present in the WWBI database: Djibouti, Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan, Morocco, Palestine and Tunisia. These are the only MENA states whose household surveys passed the WWBI’s data quality filters (World Bank, 2018). The following observations are only representative of these states in the region.

The MENA region has on average high levels of public sector employment; but be wary of averages

The WWBI confirms what is often stressed (Hertog, 2019): the region has high levels of public sector employment. Public sector employment represents close to 26% of total employment on average for the seven MENA states in the WWBI database. This is roughly 11 percentage points higher than the average rate of public sector employment for the 108 non-MENA states in the WWBI database.

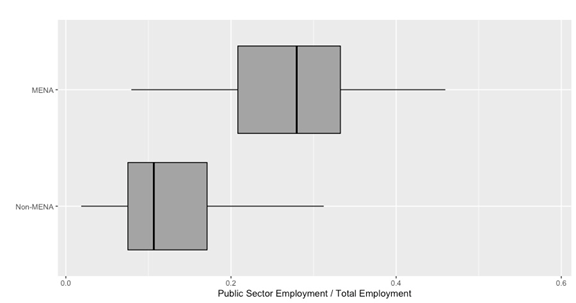

Figure 1 presents box plots of the distribution of MENA and non-MENA states’ rates of public sector employment, measured as the public sector’s share of total employment. The MENA box plot’s greater rightward skew indicates that rates of public sector employment are generally higher in the MENA region. But the MENA box’s wide length (the distance between the third and first quartile rates of public sector employment among MENA states) suggests that the region’s high average masks large sub-regional differences in rate(s) of public sector employment.

Figure 1: Distribution of rates of public sector employment

Source: Author’s visualisations based on WWBI data

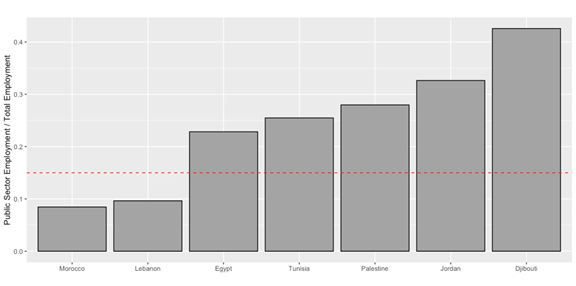

Figure 2 highlights these differences. Each box represents a MENA state’s average rate of public sector employment. The red horizontal line captures the average rate of public sector employment for all states in the WWBI database. Lebanon and Morocco’s mean rates of public sector employment are far below the global mean. At the other extreme, Djibouti and Jordan’s rates of public sector employment are more than double the global mean, and triple Lebanon and Morocco’s rates of public sector employment.

Figure 2: Average rates of public sector employment across MENA states

Source: Author’s visualisations based on WWBI data

Female employment in MENA: equally low in the public and private sector

Scholars note that though rates are low, women are increasingly joining the MENA region’s public sectors (Assaad and Barsoum, 2019). The winnowing gender gap in education, gendered wage discrimination and norms against women participating in the informal economy may drive this trend. As a result, there could be a public sector bias in women’s labour force participation in the region.

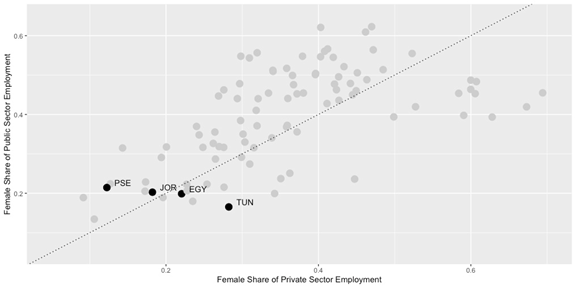

The WWBI finds little evidence of this bias. Figure 3 plots mean rates of women’s share of paid public sector (y axis) and private sector (x axis) employment for all states with female labour force data in the WWBI database. The spotted line at a 45-degree angle marks parity in female paid labour force participation rates in the public and private sector.

Figure 3: Share of paid female employment in the public versus private sector

Source: Author’s visualisations based on WWBI data

The four MENA states with female labour force data are marked in black: Egypt (EGY), Jordan (JOR), Palestine (PSE) and Tunisia (TUN). These states exhibit markedly lower average rates of paid female labour force participation in the public (0.20 versus 0.40) and private sector (0.20 versus 0.37) than in non-MENA states. In terms of public sector bias, however, mean differences in rates of paid female public employment minus female paid private sector employment are not statistically significant between MENA and non-MENA states.

Finally, as with the size of public sectors, there are noticeable within-MENA differences in women’s rates of public versus private sector employment. Women represent 21% of paid public sector employment in Palestine. This is nine percentage points higher than women’s share of paid private sector employment. In contrast, Tunisian women have greater rates of labour force participation in the private sector than public sector. Tunisian women constitute 28% of paid private sector employment, 12 percentage points higher than their share of paid public sector employment.

No urban bias in public sector employment

If public sector employment is a supreme form of political patronage, one may expect an urban bias in the make-up of public sector employees. Rulers may compensate supporters in urban centres with public sector jobs to the detriment of citizens on the rural periphery.

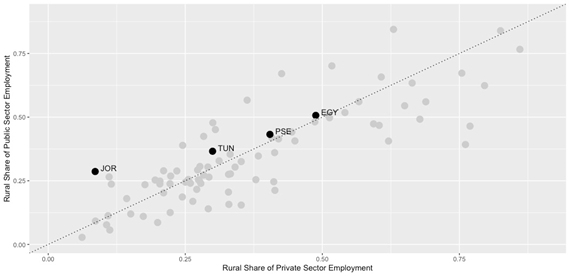

The WWBI presents little evidence of an urban bias in public sector employment in the MENA region, and beyond. Figure 4 plots states’ mean rates of rural residents’ share of paid public sector (y axis) and private sector (x axis) employment. Greater rates of rural private sector employment versus rural public sector employment would suggest an urban bias in public sector hiring. Yet Figure 4 displays near symmetry in the rates of paid public and private sector employment among rural residents in Tunisia (TUN), Palestine (PSE) and Egypt (EGY).

Figure 4: Share of rural employment in the public versus private sector

Source: Author’s visualisations based on WWBI data

Jordan (JOR), however, is an outlier: 29% of paid public sector employees in Jordan live in rural locations. This is more than three times higher than rural residents’ share of paid private sector employment. Only Lesotho, the Solomon Islands and Timor Leste’s public sectors surpass Jordan’s rural bias in public sector employment. This bias is unsurprising to Jordan experts. The ruling Hashemite regime has historically privileged the country’s rural, ‘Transjordanian’ population – its traditional pillar of support (Yom, 2014) – with public sector employment (Marie Baylouny, 2008).

How exceptional are patterns of public sector employment in MENA? The WWBI database tells us that the region’s public sectors are generally larger and much more male than average. The WWBI also uncovers substantial differences in the size and composition of public sectors within the MENA region.

The origins and socio-economic consequences of these differences merit further inquiry. By exposing cross and sub-regional differences and similarities in public sector employment, the WWBI database is an excellent resource for scholars to revisit old assumptions and generate new hypotheses on the political economy of public sector employment in MENA.

Further reading

Assaad, Ragui, and Ghada Barsoum (2019) ‘Public employment in the Middle East and North Africa’, IZA World of Labor.

Desai, Raj, Anders Olofsgård and Tarik Yousef (2009) ‘The logic of authoritarian bargains.’ Economics & Politics 21(1): 93-125.

Guay, Jennifer (2019) ‘From Gender Gaps to Corruption: 5 Lessons from the First Public Work Survey’, Apolitical, 30 January.

Hertog, Steffen (2019) ‘The Role of Cronyism in Arab Capitalism’, in Crony Capitalism in the Middle East: Business and Politics from Liberalization to the Arab Spring.

Jakiela, Pamela (2018) ‘Three Lessons from the World Bank’s New Worldwide Bureaucracy Indicators Database’, Center for Global Development, 5 December.

Malik, Adeel, and Bassem Awadallah (2013) ‘The economics of the Arab Spring’, World Development 45: 296-313.

Marie Baylouny, Anne (2008) ‘Militarizing welfare: neo-liberalism and Jordanian policy’, The Middle East Journal 62(2): 277-303.

World Bank (2018) ‘Worldwide Bureaucracy Indicators: Explanatory Note on the Dataset’, Bureaucracy Lab.

Yom, Sean (2014) ‘Tribal politics in contemporary Jordan: The case of the Hirak movement’, The Middle East Journal 68(2): 229-247.