In a nutshell

Why certain regions or types of workers have jobs less amenable to working from home is a key issue for the design of public policies.

There would be substantial benefits from improving access to digital technologies in MENA, both in normal times and during the pandemic.

But since the adoption of new technologies does not happen overnight – especially when the baseline level is very low as in the MENA region – a broader response stimulating the economy and supporting those who cannot find a job is key.

With the spread of Covid-19 and the implementation of social distancing measures, identifying who can work from home has become a critical question.

In a new article, we estimate who has the jobs more amenable to working from home in 53 countries, including three from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA).

Out of those three, we find that Jordan ranks best in terms of its jobs’ amenability to working from home, Egypt is at middle and Tunisia at the bottom. This is not surprising given that Jordan has a much higher rate of internet penetration, a factor that is critical to working from home.

But there are dramatic differences within countries as well. Less educated, older and informal workers are substantially less likely to have jobs amenable to working from home in each of the three countries.

This is driven by less educated and informal workers having jobs more intensive in physical tasks that cannot be done at home, and by older workers being less likely to use information and communication technologies (ICT).

Women in MENA have jobs more amenable to working from home. This is because women have jobs less intensive in physical tasks that are more likely to be location-specific and thereby cannot be done at home. Accordingly, they are more likely to use ICT at work than men. But these patterns across genders should be interpreted with caution, since our results do not consider other important factors driving gender differences during the pandemic.

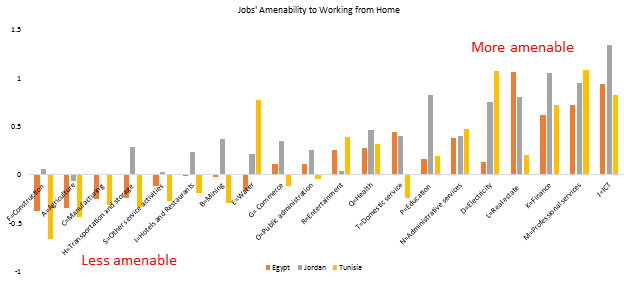

First, the probability of working in a sector considered ‘essential’ may be different across genders. Jobs in construction, agriculture and transport tend to be dominated by mean, and also rank low in their amenability to working from home (see chart), but they have typically been considered ‘essential’ in several economies. That is, workers in those sectors can usually keep their jobs despite being unable to work from home.

Second, gender-biased social norms regarding the division of childcare or home schooling in the family may affect women’s jobs disproportionately. Even in the United States, a recent survey shows that while almost half of men say they do most of the home schooling, only 3% of women agree.

In addition to providing new stylised facts, our estimates can help shed light on why certain regions or types of workers have jobs less amenable to working from home, which is a key issue for the design of public policies.

For example, the policy response would be very different if the low amenability to working from home is driven by jobs being too physically intensive rather than by people not using ICT at work. If the former is true, policies to help workers find another occupation or to provide income-support might be more adequate.

In contrast, if the amenability to working from home is low because people do not use ICT at work to conduct interpersonal tasks, then policies that give firms incentives to use more ICT or to increase digital literacy among workers might be the way to go.

Finally, if people cannot work from home because they lack internet connectivity at home, the policy response would be to address the bottlenecks that keep people from connecting online.

The benefits of improving access to digital technologies in MENA cannot be emphasised more, both in normal times and during the pandemic. In fact, a recent study shows that the rapid rollout of mobile broadband in Jordan since 2010 had dramatic impacts on female labour force participation, and on the employment rates of skilled women. Moreover, higher internet access was also linked with a reduction in gender-biased social norms, early marriage and fertility.

But the adoption of new technologies does not happen overnight, especially when the baseline level is very low as in the MENA region – less than half of the workers in the three countries we analysed have internet access at home and only 13% use the internet in their jobs. Thereby, a broader response stimulating the economy and supporting those who cannot find a job is key.