In a nutshell

Compared with the Covid-19 containment measures in many other countries, one distinguishing feature of Turkey’s is its age-specific curfew: the country’s working-age population was never confined to their homes.

Nonetheless, trade still dried up: Turkish manufacturers started finding it increasingly difficult to trade with China and their major European partners.

Developing countries like Turkey need to re-evaluate their practices in ‘hub and spoke’ trade systems and make room for ‘functional redundancies’ in preparation for future extreme crises like Covid-19.

The last four decades have seen the cross-border vertical fragmentation of industrial production along what have come to be known as ‘global value chains’. Goods are shipped from country to country before they reach their final consumers whose purchases are truly ‘made in the world’.

The Covid-19 pandemic has dramatically disrupted the world economy with the sharp decline in demand arising from diverse containment measures around the globe and factory shutdowns due to concerns about workers’ health. The pandemic came as a series of thunderbolts that have hit the major hubs of global value chains one after the other: first China, then Europe and finally the United States.

The World Trade Organization predicts that world trade will fall by between 13% (optimistic scenario) and 32% (pessimistic scenario) in 2020. The decline may surpass the trade slowdown caused by the global financial crisis of 2008-09.

The growth of world trade was already sluggish in 2019 due to trade tensions and decelerating economic growth. Add to that the colossal economic impact of the pandemic, and ‘spoke’ countries – such as Turkey – may stand to lose more in the medium and long run than others by this unexpected shock to the international trading system.

Containment measures

Turkey has been on the top-ten list of Covid-19 cases for nearly a month now. By 14 May 2020, the number of confirmed cases and confirmed deaths has reached almost 144,000 and 4,000, respectively. The country has been reported as among the front-runners of the fastest rising infection rates in the world, partly because of the increasing testing capacity, with nearly 1.5 million tests carried out by 14 May.

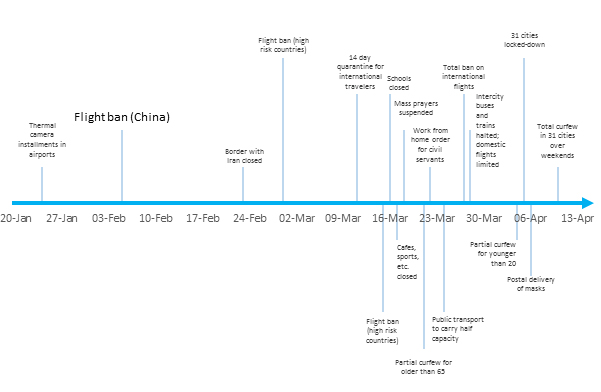

Turkey has enacted a series of containment measures, summarised in Figure 2. The first was the instalment of thermal cameras in major airports in late January. The country was admittedly slow to stop flights from Iran (the second epicentre of the pandemic); but there was a speedy response in stopping flights to and from China on 3 February followed by successive flight bans with other high-risk countries. The 14-day quarantine restriction for international travellers was introduced in 11 March when the first confirmed case was announced.

Figure 1. Timeline of Covid-19 containment measures in Turkey

Note: Author’s illustration using data from Oxford Covid-19 Government Response Tracker, more on https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research-projects/coronavirus-government-response-tracker

Social distancing measures took effect in Turkey in mid-March, much earlier than in many Western countries. Schools were closed; mass prayers were suspended; restaurants, cafés, sports and cultural facilities halted their activities; and all public events were cancelled. A work-from-home order was issued for non-essential civil servants.

Travel was restricted. Borders were closed on 27 March to all but returning citizens; intercity buses and trains were halted; and domestic flights were limited. No entry or exit was allowed for the residents of 31 large cities.

In its lockdown arrangements, Turkey adopted an age-related partial curfew. Non-essential movement of people over 65 and under 20 years of age was banned. There were no bans on the movement of working-age population, reflecting the government’s priority of not halting production. A total curfew at weekends and on national holidays was put in place in mid-April.

A greater collapse of trade

Turkey had a bad year in 2019 in terms of its foreign trade, which was already lower than 2018 levels due to the recession with which the country was struggling in the previous year. Any further decline in trade would be nothing but disruptive – yet it has happened.

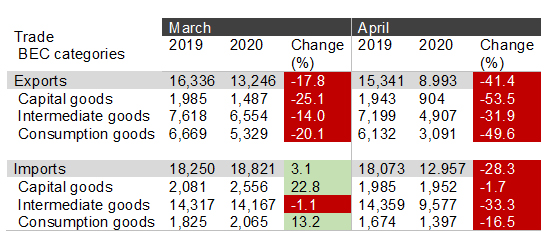

Exports immediately responded to the crisis with a 17.8% decline in March compared with the same month in 2019. Demand from Turkey’s major trade partners dried up. Imports still showed growth in March for at least three reasons:

- First, production in Turkey was mostly business as usual in the first ten days of the month.

- Second, Turkey was a latecomer to the Covid-19 scene and import orders had been given at least a month before – and even longer for capital goods imports.

- Third, even after the first confirmed case of Covid-19, some Turkish producers continued to stock up their raw materials and intermediate inputs to avoid congestion in trade routes once lockdown restrictions are lifted.

Nevertheless, in April, both exports and imports were struck very hard. Compared with the April 2019, a massive contraction in exports amounting to 41.4% and a smaller yet still large decline in imports at 28.3% was in store for Turkey. Capital goods and consumption goods exports were halved and intermediate goods imports declined by a third.

Table 1: The recent slowdown of trade in Turkey (million $)

Source: Ministry of Trade Monthly Data Bulletins (March and April 2020)

Why so massive?

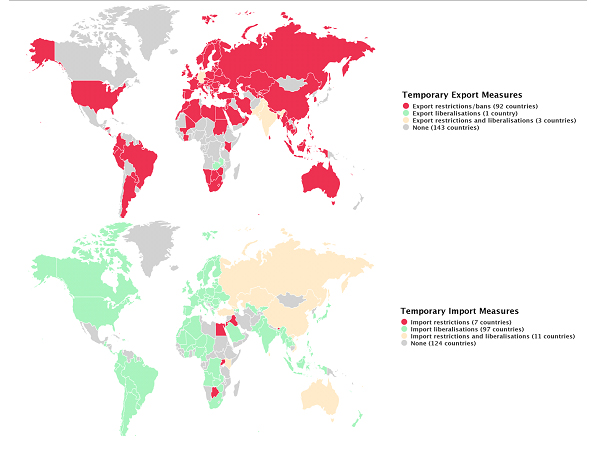

As happened in many other countries, Turkey’s government has adopted swift trade measures to restrict the exports of vital medical supplies and some other goods while liberalising imports of these materials.

Figure 2 shows temporary export and import measures around the globe as of 10 May. But these trade measures alone would not cause a major decline in international trade for Turkey and would be of limited effectiveness, as argued by Bernard Hoekman, Matteo Fiorini and Aydın Yıldırım in a more general case in the new VoxEU eBook.

Figure 2: Global maps of Covid-19 temporary trade measures (10 May 2020)

Source: https://www.macmap.org/covid19

The root of the problem was elsewhere. Just as in the 2009 Great Trade Collapse, the 2020 trade slowdown has a large demand-side component. In the words of Richard Baldwin, who has coined the phrase Greater Trade Collapse, ‘the world is experiencing a massive, difficult-to-comprehend shock that has scared consumers and investors into a wait-and-see crouch.’ What makes the 2020 collapse different from 2009 is the accompaniment of the demand-side shock by a colossal supply-side shock – a perfect storm hitting a multitude of sectors and geographies.

In many countries, economic translation of containment measures was the abrupt halt of consumption and production simultaneously. One distinguishing feature of Turkey compared with many Western countries was its age-specific curfew. The working-age population of the country was never confined to their homes except for the unavoidable case of workers contracting the virus. Even in that case, factories were shut down but then reopened after the infection was over, as I discuss in a VoxEU column.

So, the adverse production effect in Turkey must have been an outcome of reduced domestic and international demand for Turkish goods coupled with deteriorated supply capacity of international partners due to Covid-19. In other words, there was a supply-chain contagion that amplified the magnitude of trade collapse compared with the 2009 trade slowdown.

During this period, Turkish manufacturers started finding it increasingly difficult or expensive to obtain the necessary imported intermediate or capital goods from China and their major European partners. Equivalently, it was harder to sell these goods to these countries for them to use in their production processes, which were heavily hit by the Covid-19 lockdowns.

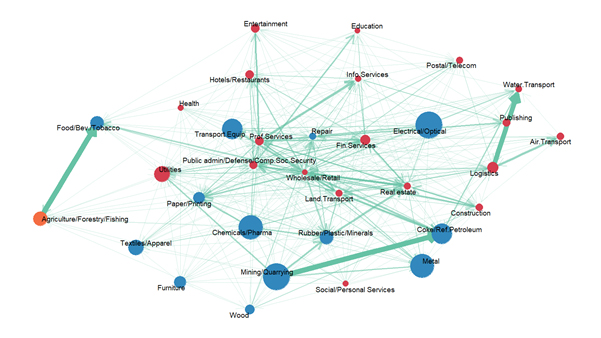

Figure 3 shows the import dependency of domestic production in Turkey. This picture by itself can pay homage to the idea of a Covid-19 triggered supply-chain contagion in production and trade. Orange, blue and red bubbles signify agriculture, manufacturing and service sectors, respectively. The size of a bubble shows the share of the sector in total imported inputs. The weight of connections reflects the strength of foreign backward integration.

As Figure 3 shows, the imported input dependency within manufacturing is particularly strong in Turkey, as in many other countries. The sectors that are more heavily dependent are chemicals, pharmaceuticals, transport equipment, electrical and optical, basic and fabricated metal, mining and coke/petroleum.

Figure 3. Import dependency of domestic production

Graphic: Alkım Karakurt

Note: The foreign intermediate inputs in sectoral production are obtained from the most recent (2012) input-output tables for Turkey. The size of a bubble shows the sector’s share in total imports of intermediate inputs. The weight of connections reflects the strength of foreign backward linkages.

Concluding remarks

After the Great Trade Collapse of 2009, trade never returned to its previous trajectory. With the Greater Trade Collapse of 2020, the world is yet to see if that will happen again.

If consumers and producers in Turkey and abroad view the Covid-19 crisis as a one-time shock, a swift recovery could be possible. But if the health crisis is persistent while uncertainty takes its place on the world stage as the new normal, both domestic and foreign components of consumption and production in Turkey will suffer in the long run. That would be heavily reflected in Turkey’s international trade.

A number of developed country governments are calling for sovereign and national supply chains. Granted, it has become abundantly clear that the lack of sane economic globalisation can be detrimental in terms of inequalities it tends to create. The sacrifice of equity for efficiency has proved to be wrong. But it must not be forgotten that a disproportionate reduction in diversification along cross-border production chains may deal a harder blow to the industrialisation efforts of developing countries like Turkey.

What seems to be the missing ingredient of the global value chains era of the last four decades in many countries, including Turkey, is functional redundancy. This can be defined as the presence of multiple components that can perform the same function. In essence, it is a practice of ‘don’t put all your eggs in one basket’ within a system that allows some components to compensate for the failure of others.

In this context, Turkey needs to re-evaluate its place in the ‘hub and spoke’ trade systems of recent years. Instead of focusing mostly on efficiency, productivity and specialisation, the country needs to make room for functional redundancies in preparation for extreme crises such Covid-19.