In a nutshell

The macroeconomic fundamentals of Lebanon’s economy have been steadily deteriorating over the past few years.

The proposed austerity budget aims to reduce the public deficit-to-GDP ratio to 7.5%, but it assumes a GDP growth rate of about 4% in 2019.

Such a growth rate is a very unlikely economic outcome given the domestic and regional political, economic and social uncertainties.

The fiscal and financial situation in Lebanon can best be characterised as critical, fluid and unstable. The macroeconomic fundamentals of the economy have been steadily deteriorating over the past few years: low GDP growth rates and low government revenues; increasing inflation rates and government expenditures; widening budget and current account deficits, estimated at about $13 billion per year; and unsustainable public debt.

Painful fiscal adjustment measures are needed in difficult circumstances (Neaime, 2004, 2008, 2010, 2015b). Achieving fiscal sustainability, rebuilding confidence and preserving the exchange rate peg to the dollar inevitably will require timely and tough fiscal adjustment measures (Neaime and Gaysset, 2017, 2018).

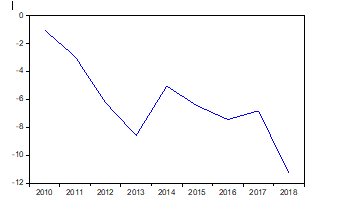

The government’s fiscal reform agenda, as highlighted in the published 2019 budget with a projected reduction in the budget deficit-to-GDP ratio (from 11.2% in 2018 to about 7.5 % in 2019 – see Figure 1), is likely to pave the way for a promising path towards reducing the country’s large debt overhang and financial vulnerabilities. (By way of comparison, during the Greek debt crisis, the budget deficit-to-GDP ratio was 10.5%.)

Lebanon’s budget seeks to unlock $11 billion of new loans pledged by foreign investors at the Economic Conference for Development Through Reforms (CEDRE) in Paris in April 2018, by instituting a variety of so-called austerity measures, as the release of the funds is conditioned on Lebanon being able to reduce its deficit by 5% over the next five years. Reducing the budget deficit by 1% over a five-year period would mean that the rate of growth of debt would be contained. That is a must to avoid a public debt crisis.

On 27 May 2019, the Banque du Liban (BDL) purchased the equivalent of $650 million of the latest issue of government bonds. This constitutes a clear signal that domestic and international sources of financing government debt are drying up and becoming too thin. A similar type of bond swap operations took place last year for the equivalent of $2.8 billion.

It is unusual for a central bank to purchase significant amounts of government debt (new issues of bonds). If this is indeed the case, then the central bank is either printing money (which will translate into higher rates of inflation) if the debt is denominated in local currency, or it is tapping its foreign currency reserves if the debt is in dollars.

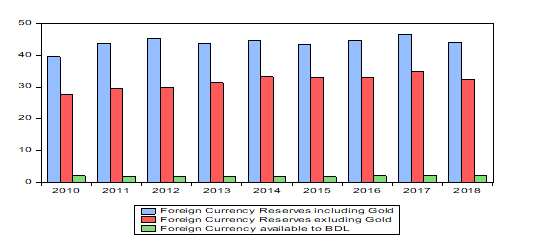

Currency reserves are usually used by the central bank to intervene in the foreign exchange market to preserve the Lebanese pound (LBP) peg to the dollar (LBP 1500 per $1) and to pay for major and essential imports such as oil, gas and wheat. Published figures on the gross foreign reserves at the central bank amounted to $44.1 billion in 2018, down to about $41 billion by end of April 2019 (see Figure 5).

The central bank’s foreign reserves excluding gold reserves – estimated at $11.7 billion in 2018 – and commercial banks’ reserve requirements – estimated at about $11 billion (10% of the current total Lebanese bank deposits, estimated at $110 billion) – amount to $22 billion (or the equivalent of 13 months of imports), which the central can use to support the Lebanese pound and settle bills for imports of necessities.

Any further capital flight (bank deposits exiting the domestic banking system) or further deterioration in either the inflow of remittances (averaging $7 billion/year and compensation to some extent for the current account deficits) or in the public’s expectation of either political, social or military turmoil could trigger a currency crisis with the public further converting their LBP bank deposits into deposits in dollars (Hakim et al 2000, 2001; Neaime 2000, 2012, 2015b; Devarajan et al, 2019).

It should also be noted that for the first time since the establishment of the pegged exchange rate regime in early 1990, a black market for the dollar has started to develop. In May, the dollar was trading at about LBP 1,540 in the black market. This is a clear signal that foreign currency liquidity (dollar liquidity) is becoming scarce in the market, translating into more pressure on the LBP.

As soon as either bank deposits in LBP or local currency debt are maturing, individuals and organisations are converting these LBP into dollars, exerting more pressure on the foreign currency reserves of the central bank. Incidentally, the available amount of foreign currency reserves the central bank can dispose of to defend the LBP is currently at $22 billion, not $41 billion as is the general belief (see Figure 5).

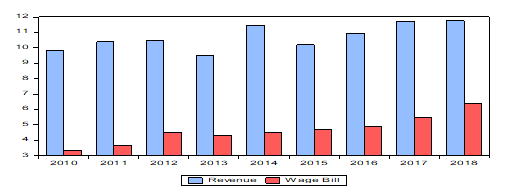

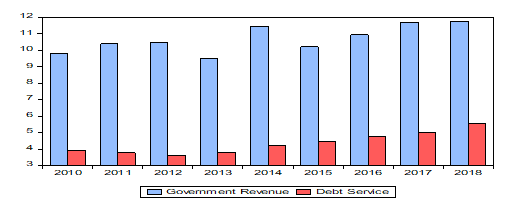

The latest increases in interest rates have increased public debt servicing to about 51% of government revenues (see Figure 3). In addition, the minimum public wage increase and the total public wage bill estimated at 54% of government revenues (see Figure 4) have exacerbated even further the budget deficit. They have put further pressure on the central bank to hold more government debt through printing money (seigniorage revenues). This has resulted in even more pressure on the inflation rate, which is already estimated at 7% in 2018.

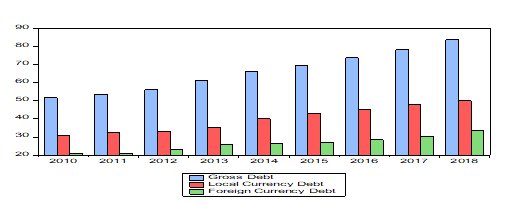

According to the Ministry of Finance, Lebanon has so far accumulated a sizable amount of public debt; $86 billion (see Figure 2) at end-March 2019 and a public debt-to-GDP ratio of 152%, and forecast to reach 180% in 2022. (Again for comparison, during the Greek debt crisis, the debt-to-GDP ratio was 142% of GDP).

In 2019, Lebanon ranks fifth in terms of the most indebted countries in the world, after Japan with a debt-to-GDP ratio of 234%; Greece: 180%; Sudan: 178%; and Venezuela: 172% (Neaime, 2015a; Neaime et al, 2018; Ndulu and O’Connell, 2019). For the first time since 2015 and during the first five months of 2019, the balance of payment registered a deficit of $5 billion; a clear signal of further capital and bank deposit flight and more pressure on the current pegged exchange rate regime.

Moreover, and given the deterioration in the economy’s macroeconomic fundamentals, Standard and Poor’s is expected to downgrade Lebanon’s public debt ratings further: from category B to C (junk bonds) by the end of summer. This will put further upwards pressure on already high rates of interest, and it will further exacerbate debt service costs and government budget deficits, as well as commercial banks’ balance sheets.

In short, it is most unlikely that the current proposed austerity budget for 2019 will be able to restore confidence in Lebanon’s economy. The reduction in the deficit-to-GDP ratio to 7.5% assumes a GDP growth rate of about 4% in 2019; a very unlikely economic outcome given the domestic and regional political, economic and social uncertainties.

Figure 1:

Budget deficit as a percentage of GDP, 2010-2018

Figure 2:

Distribution of gross public debt (US$ billion), 2010-2018

Figure 3:

Government revenues and public debt service (US$ billion), 2010-2018

Figure 4:

Government revenues and public wage bill (US$ billion), 2010-2018

Figure 5:

Foreign currency reserves at the central bank (US$ billion), 2010-2018

Source: Banque Du Liban (BDL) and the Lebanese Ministry of Finance

Further reading

Devarajan, Shanta, Indermit Gill and Kenan Karakülah (2019) ‘Debt Growth and Stability in Africa: Speculative Calculations and Policy Response, Discussion Draft’, 21 May.

Hakim, Sam, Simon Neaime and CC Paraskevopoulos (2000) Perspectives on the Integration of Financial Markets – Global Financial Instability.

Hakim, Sam, and Simon Neaime (2001) ‘Performance and Credit Risk in Banking: A Comparative Study for Egypt and Lebanon’, ERF Working Paper No. 137.

Ndulu, Benno, and Stephen O’Connell (2019) ‘Africa’s Development Debts’, paper prepared for AERC plenary session, Cape Town, 2 June .

Neaime, Simon (2000) The Macroeconomics of Exchange Rate Policies, Tariff Protection and the Current Account: A Dynamic Framework, AFP Press.

Neaime, Simon (2004) ‘Sustainability of Budget Deficits and Public Debt in Lebanon: A Stationarity and Cointegration Analysis’, Review of Middle East Economics and Finance 2(1): 43-61.

Neaime, Simon (2008) ‘Twin Deficits in Lebanon: A Time Series Analysis’, Lecture and Working Paper Series No. 2, Institute of Financial Economics, American University of Beirut.

Neaime, Simon (2010) ‘Sustainability of MENA Public Debt and the Macroeconomic Implications of the US Financial Crisis’, Middle East Development Journal, 2: 177-201.

Neaime, Simon, (2012) ‘The Global Financial Crisis and the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership’, Europe and the Mediterranean Economy.

Neaime, Simon (2015a) ‘Sustainability of Budget Deficits and Public Debts in Selected European Union Countries’, Journal of Economic Asymmetries 12: 1-21.

Neaime, Simon (2015b) ‘Twin Deficits and the Sustainability of Public Debt and Exchange Rate Policies in Lebanon’, Research in International Business and Finance 33: 127-43.

Neaime, Simon, and Isabelle Gaysset (2017) ‘Sustainability of Macroeconomic Policies in Selected MENA Countries: Post Financial and Debt Crises’, Research in International Business and Finance 40: 129-40.

Neaime Simon, and Isabelle Gaysset (2018) ‘Financial Inclusion and Stability in MENA: Evidence from Poverty and Inequality’, Finance Research Letters 24: 230-37.

Neaime, Simon, Isabelle Gaysset and Nasser Badra (2018) ‘The Eurozone Debt Crisis: A Structural VAR Approach’, Research in International Business and Finance 43: 22-33.