In a nutshell

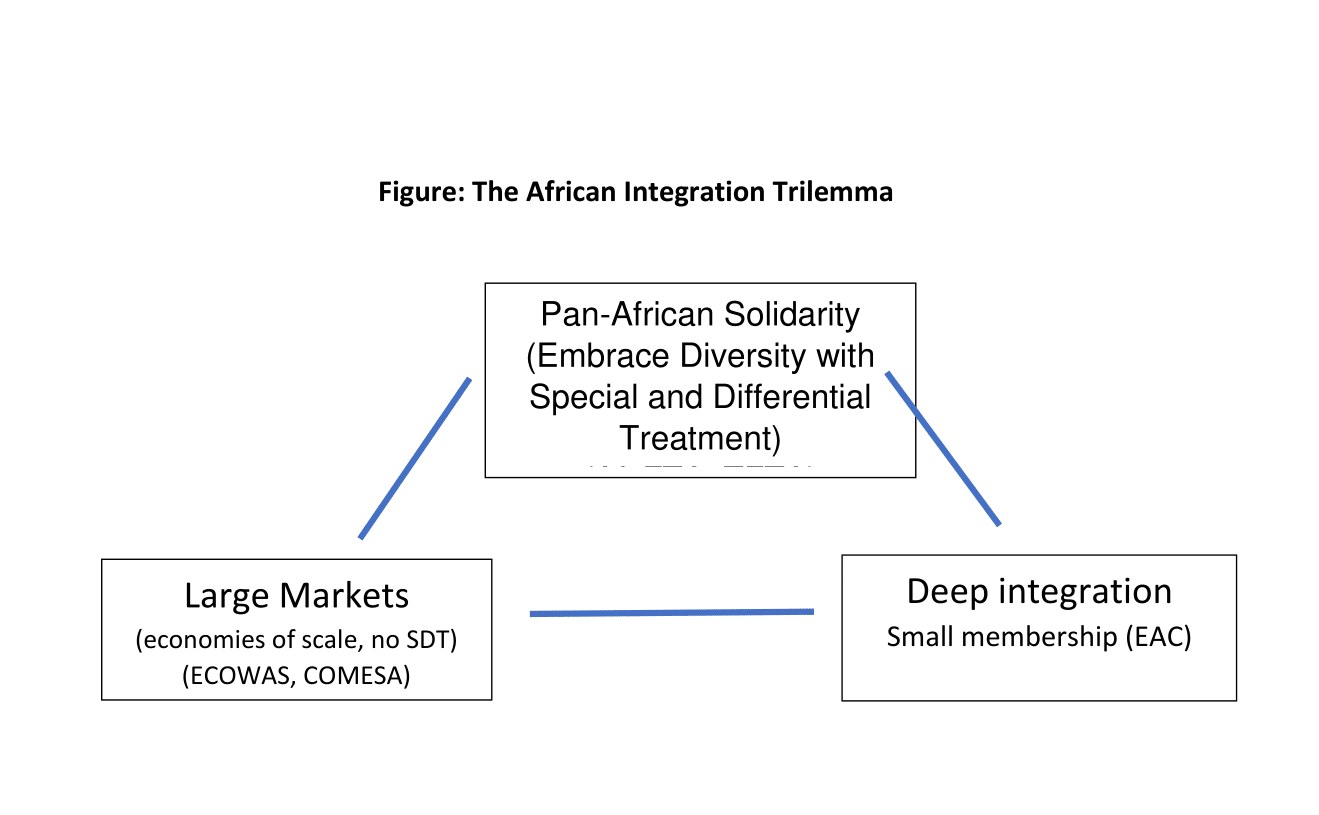

Agenda 2063 of the African Union has three competing objectives: pan-African solidarity across the continent’s diverse countries; large membership to break the curse of small markets; and deep integration to reap all the benefits of integration.

Solidarity calls for special and differential treatment segmenting markets; fully reaping economies of scale requires large membership; and deep integration requires trust, which is easiest to achieve with a small membership.

These objectives are incompatible, so it is not surprising that, as of early 2019, no North African countries had ratified the agreement on an African continental free trade area.

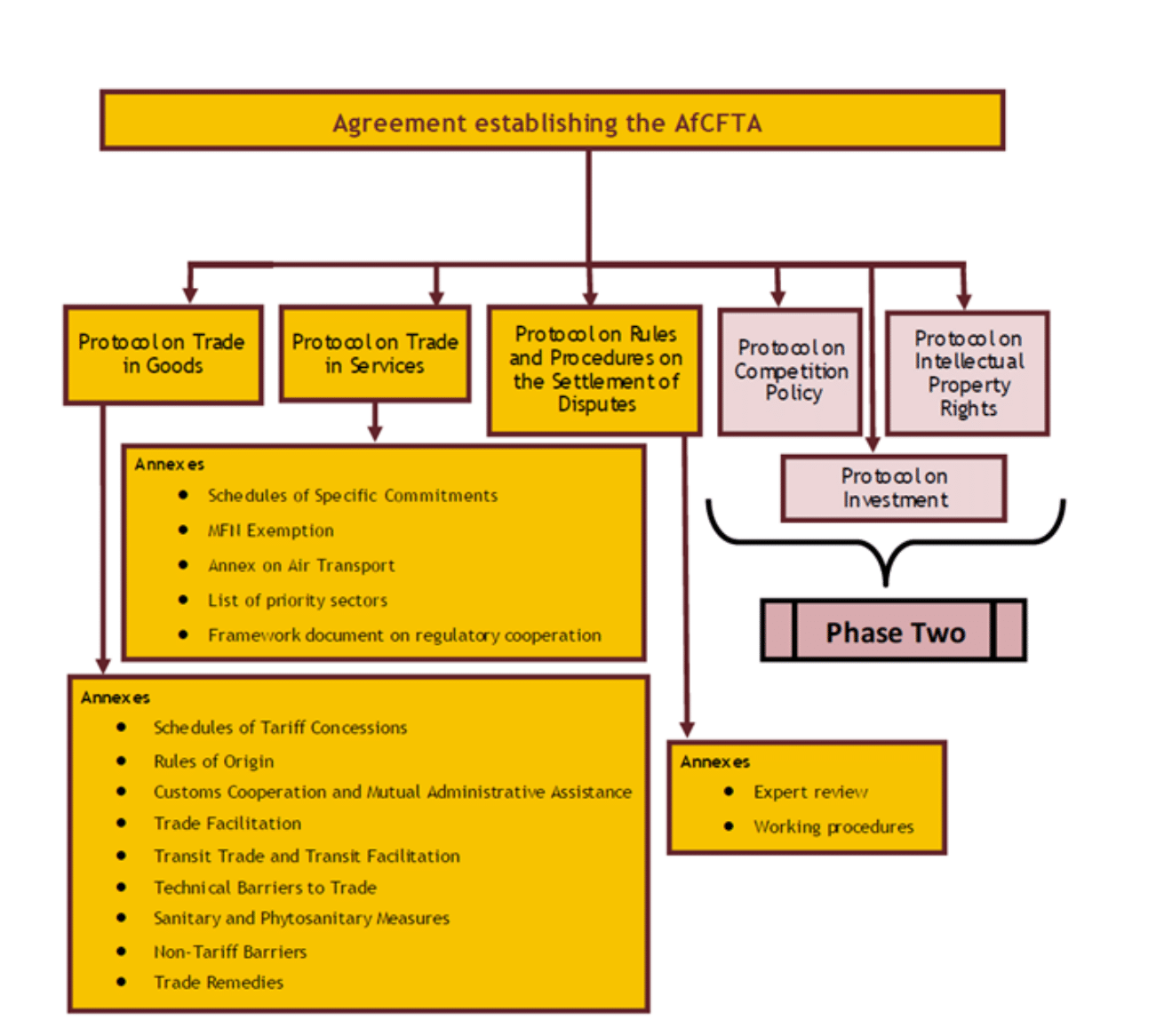

In March 2018 in Kigali, 44 of the 55 members of the African Union (AU) signed an agreement to establish an African continental free trade area (AfcFTA). The architecture of the AfcFTA has two phases (see Figure 1):

- Phase I includes three protocols – Trade in Goods, Trade in Services, and procedures on the Settlement of Disputes – and associated annexes.

- Phase II includes three protocols – Competition Policy, Intellectual Property Rights, and Investment.

By January 2019, 18 out of the 22 ratifications needed for the agreement to come into force had taken place. Once the 22 ratifications are in hand, the AfcFTA will have the largest membership of a free trade area in the world since the launch of the GATT (now the World Trade Organization, WTO) 70 years ago. If all African countries have joined the free trade area by 2030, the market size would include 1.7 billion people with an estimated US$6.7 trillion of cumulative consumer and business spending.

Three competing objectives in the AU’s Agenda 2063 have slowed ratification, with none of the North African countries so far among the 22 required signatories. The three objectives are:

- African solidarity (to accommodate all countries).

- Large markets (no policy-imposed impediments to trade).

- Deep integration to reap all the benefits of integration.

Typically, membership of the eight regional economic communities (RECs) through which integration is to continue to take place includes resource-rich and resource-poor countries, coastal and landlocked countries, and large and small countries in population density. African countries are also highly diverse along multiple dimensions (ethno-linguistic, religious, biological).

These diversities point to an ‘integration trilemma’ facing the 2063 agenda of integration. This trilemma is shown in Figure 2, where for each objective, further distance from the vertex indicates less achievement. Figure 2 suggests that even if integration were to progress smoothly within each REC, Africa cannot be at all three vertices simultaneously. The 2019 edition of African Economic Outlook discusses these challenges facing finalisation of the AfcFTA (Africa Development Bank, 2019).

Solidarity requires special and differential treatment (SDT) for least developed countries (LDCs) and financial resources (which are in short supply) to compensate for integration costs. Solidarity requires trust, which falls as membership size increases. During the AfcFTA negotiations, South Africa strongly opposed financial compensation (Parshotam, 2018). The compromise is that SDT is to be built into the Treaty on a case-by-case basis and LDCs have an extended implementation period.

SDT accommodates this diversity but at the cost of market fragmentation. Thus the Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA) among the Common Market for East and South Africa (COMESA), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the South Africa Development Cooperation (SADC) or the AfcFTA can achieve solidarity but at the costs of a continental market and deep integration.

Fully reaping economies of scale requires large membership (COMESA, ECOWAS) and low trade barriers. This precludes SDT for the LDCs, which segment markets by raising trade costs and effectively limits the size of the market.

Deep integration as in the case of the EAC results in the integration of financial markets and the mobility of people. Deep integration requires trust. Trust is more easily achieved in a small membership setting (such as the East African Community). Because of the lack of trust needed to delegate authority to supranational institutions, embracing diversity to satisfy political objectives impedes deep integration.

African diversity also points to an implementation conundrum. On the one hand, because of diversities – such as between coastal and landlocked countries – potential gains from closer economic integration are large. On the other hand, realising these gains requires financial resources necessary to compensate countries with large differences in expected gains from closer integration.

The wasteful Common Agricultural Policy amounting to 1% of European Union GDP has often been explained as a political compromise between France and Germany whereby German manufacturers gained access to the French market while German taxpayers helped to subsidise French farmers. In the African context, the AU could only finance 44% of its budget from member state contributions. Reaching financial viability via a 0.2% levy on all eligible goods imported to the continent could be controversial under current WTO law (Economic Commission for Africa, 2017).

Deep integration requires the establishment of supranational entities and delegation of authority, which in turn requires trust and implementation capabilities. Trust is difficult to build under any circumstances but is particularly so in Africa’s landscape of great diversity.

The protracted TFTA negotiations illustrate the difficulties encountered during the AfcFTA negotiations. The negotiations principles of the TFTA follow a ‘variable geometry’ under the ‘acquis’ (that is, nothing agreed by the COMESA, EAC and SADC free trade agreements, FTAs, can be undone).

Instead of merging the three FTAs into one, the TFTA has evolved into a new FTA encompassing the three existing RECs. These developments raise the question of how, under the necessity of preserving the acquis to maximise membership by accommodating diverging interests, the AfcFTA, will be able to overcome the heterogeneity of interests across RECs.

In terms of Figure 2, moving towards the top vertex is through ‘shallow’ integration at the sacrifice of economic efficiency. It is also unlikely that the brake on integration caused by the negotiation principles in the TFTA will reduce heterogeneity of preferences across members. A fortiori, this will be the result of the negotiations under the AfcFTA.

The TFTA, which was initiated in 2008 and signed in 2015, was intended to reconcile the challenge of overlapping REC membership. This overlap has traditionally permitted governments to cherry-pick which commitments they uphold. The TFTA objectives are:

- Removing tariffs and non-tariff barriers, and implementing trade facilitation measures to include a harmonisation of rules of origin.

- Applying the subsidiarity principle to infrastructure to improve the transport network.

- Fostering industrial development.

But to keep momentum going and to accommodate the diversity of interests among partners, negotiations to set up a ‘single undertaking’ to establish a proper FTA veered towards a ‘variable geometry’ under the principle of flexibility to allow the co-existence of different trading arrangements.

‘[T]he principle of flexibility … allows progression in cooperation among Member /Partner States in a variety of areas at different speeds. The TFTA will allow the co-existence of different trading arrangements which have been applied within COMESA, EAC, and SADC member states and any trading arrangements that may be reached during the negotiations. The principles of variable geometry, reciprocity and acquis are complementary’ (Erasmus, 2013).

This means that the negotiations principle of a single undertaking where ‘nothing is agreed until everything is agreed’ no longer made sense since the result would be a new FTA. This implies that the parties probably did not agree to a prior agreement about the agreement.

Not surprisingly, under the variable geometry with the acquis, the three blocs reached a common position on the proportion of tariff lines to be liberalised, but failed to agree on the common external tariff to be applied on sensitive products (maize, cement, sugar, second-hand clothes, spirits, plastics, electronic equipment, etc.). Other technical difficulties besieged the completion of Phase I on non-tariff barriers (article 10 and annex 3), rules of origin (article 12 and annex 4), trade remedies (articles 16-20 and annex 2), and dispute settlement (article 10 and annex 10) – see Luke and Mabuza (2015).

Despite agreeing that the three RECs would work towards merging into a single REC, this did not happen. Instead, the TFTA evolved into a new FTA encompassing the three existing RECs because it is based on preserving the acquis, a fear voiced by Erasmus. The expression of these disagreements had greater intensity because the negotiations started from the acquis, which is the point reached by the COMESA, EAC and SADC negotiations. Phase II of the TFTA negotiations covering competition policy, intellectual property rights and investment movement of business persons are still on the table because of difficulties encountered with the acquis and variable geometry.

Negotiations on ‘technalities’ are still besieging Phase I of the AfcFTA. These technicalities include, in particular, agreement on a common set of rules of origin, a dispute settlement mechanism and trade remedies. The acquis in the RECs will also likely prevail during Phase II negotiations of the AfcFTA.

As of January 2019, 18 of the 22 necessary ratifications have been obtained. Under these difficult circumstances with multiple objectives, it is not surprising that no North African country has yet ratified the AfcFTA.

Further reading

Africa Development Bank (2019) African Economic Outlook 2019: Integrating for Africa’s Economic Prosperity.

Economic Commission for Africa (2017) Assessing Regional Integration in Africa VIII: Bringing the Continental Free Trade Area About.

Erasmus, Gerhard (2013) ‘Redirecting the Tripartite Free Trade Area Negotiations?’, tralac Trade Brief No. S13TB02/2013.

Luke, David, and Zodwa Mabuza (2015) ‘The Tripartite Free Trade Area Agreement: A Milestone for Africa’s Regional Integration Process’, Bridges Africa 4(6).

Parshotam, Asmita (2018) ‘Can the Africa Continental Free Trade Area Offer a New Beginning for Trade in Africa’, SAIIA Occasional Paper No. 280,

Figure 1:

Phases of the African continental free trade area (AfCFTA)

Source: tralac, African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) FAQs

Figure 2:

The African integration trilemma