In a nutshell

More transparency in the management of Iran’s exchange rate system, in line with the priorities for the economy, would help to stem speculative attacks.

The menu of options could include consideration of a basket peg, based on the shares of trading partners, or a peg to the oil price.

Improving fundamentals – including by reining in large fiscal deficits and ensuring fiscal sustainability – would result in fewer risks of abrupt sharp discretionary devaluation.

The announcement by the Trump administration that the United States is withdrawing from the 2015 Iran nuclear deal has put the agreement in jeopardy. Other signatories, including European countries, China and Russia would like to uphold their agreements.

But the way forward is likely to prove difficult given prospective sanctions that could be imposed by the United States on firms operating in Iran. Indeed, several major companies have already announced that they are pulling out of the country by November 2018 unless they are exempt from the US penalties.

Even before the announcement, the Iranian rial was depreciating because of several factors, including expectations of the US policy shift. Immediately following the announcement, the rial tumbled in the unofficial market on rising expectations that sanctions could constrain the availability of foreign currencies in the country.

This comes on the heels of lingering challenges that have not been fully eliminated since the nuclear deal was established. De facto, the agreement did not result in full resumption of investment and exports to ease the longstanding constraints on the Iranian economy since sanctions were first imposed.

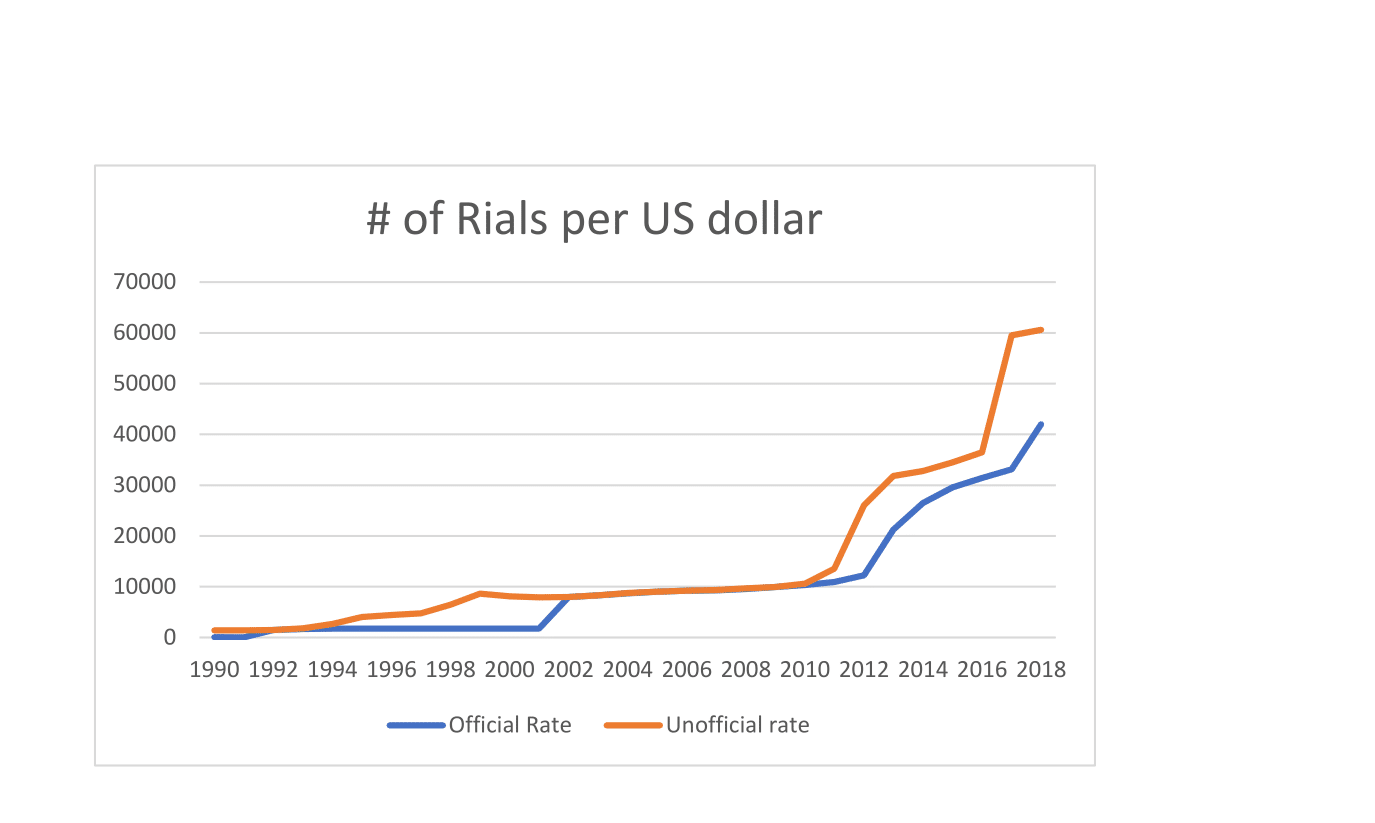

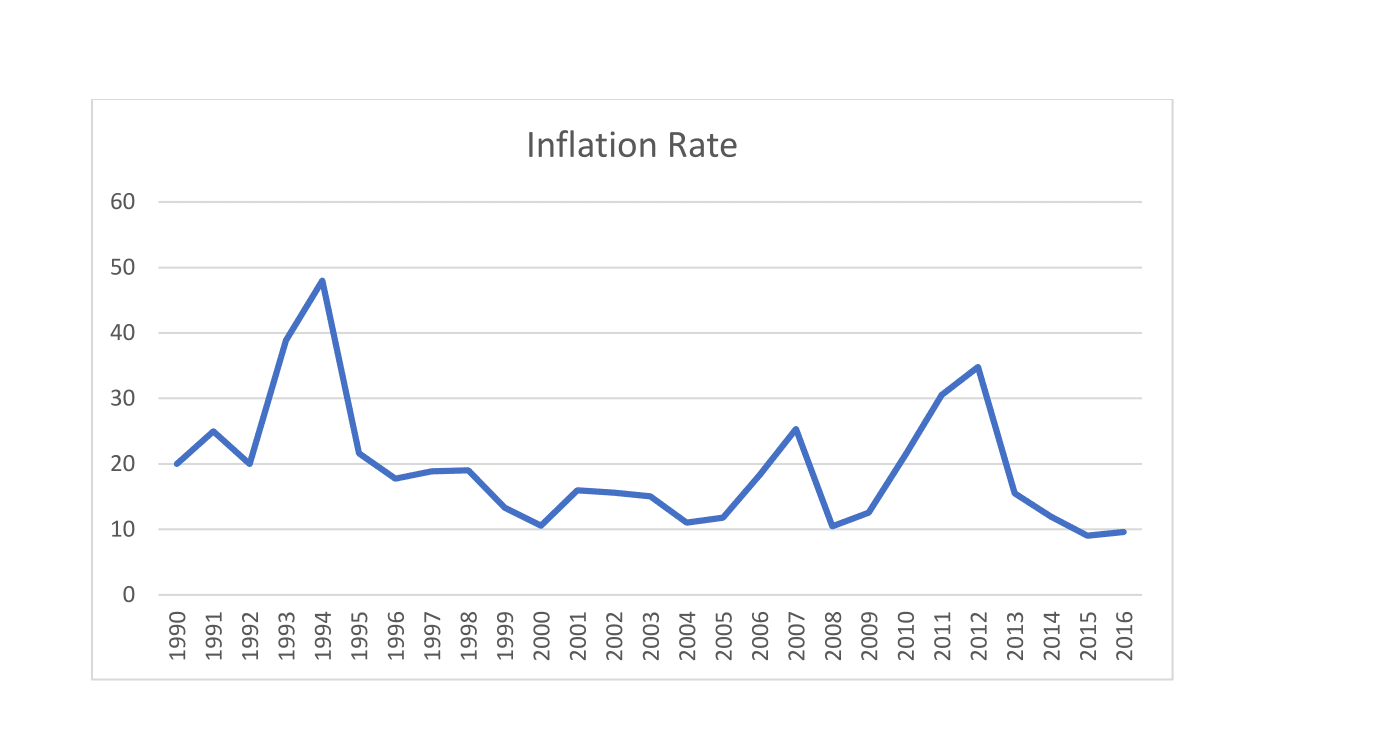

In recent decades, the economy has experienced several shocks to its currency. Most of the time, the depreciation of the rial has been accompanied by inflationary pressures. For example, when an exchange rate shock happened during the 2013 financial sanctions on Iran, the inflation rate was at 37%. Depreciation increases the cost of imports and generates inflationary pressures.

But the recent drastic depreciation of the rial took place while the inflation rate was in single digits, low by historical standards. Low inflation could be credited to the recent contractionary monetary policy in Iran. Following the nuclear deal and the removal of sanctions, the central bank signalled its commitment to curbing inflation by raising the interest rate on saving deposits to 20%. This policy was successful in reducing the inflation rate. The March 2018 reading of inflation recorded 9.2%.

Meanwhile, in the absence of productive investment opportunities in the economy, the high interest rate provided an outlet for the public to protect their savings against expected future inflation by depositing them in the banking system. As inflation kept going down, the central bank began reducing the interest rate on deposits gradually – from 20% to 18% and then 15% – to bring it into line with the inflation rate with a goal of reducing the real interest rate and encouraging private investment.

At that time, in the absence of good investment opportunities elsewhere, the public took its deposits out of the banking system and converted them into foreign currency and gold as a safe haven to cover themselves against possible inflation in future. Figures 1 and 2 show the historical values of the rial and inflation since 1990.

As the value of the rial started to go down, the central bank faced the dilemma of either intervening to support the currency or letting the market operate freely. In parallel, monetary policy became focused on curbing inflation, hoping that low inflation expectations would help to foster confidence in the economy and solidify the public’s trust in holding their savings in domestic currency given a stable outlook for the exchange rate and inflation.

Nonetheless, other factors, such as the prospect of the collapse of the nuclear deal, sparked widespread demonstrations on the streets, voicing the public’s dissatisfaction with economic policy and inequality against a backdrop of rising inflation expectations. Overall, the public’s mistrust of the future of the rial, coupled with speculative attacks on the currency, led to its fall from 60,000 to 70,000 rials per dollar.

Iran’s government and central bank blamed the change in the value of the rial on speculators in the currency market and cracked down on foreign exchange traders, arresting several and freezing hundreds of dealers’ accounts. The central bank reversed its interest rate policy, allowing banks to increase the rate on saving deposits to 20% in order to attract funds away from foreign currency trading and to increase people’s confidence in rial holdings.

Against the backdrop of these policies, the central bank was able to calm the market for a short period, but at a cost of foreign currency shortages and long lines of customers waiting to exchange rials for dollars. Subsequently, the exchange rate system moved to a triple currency system from the previous dual exchange rate system.

At that point, the government announced a one exchange rate policy at 42,000 rials per dollar while imposing capital controls by enforcing tighter restrictions on foreign currency outflows. Currently, limited foreign currency supply is available to the public at the official exchange rate, based on the listed priorities. Other traders find the currencies they need in the black market: the rate there currently stands at around 60,000 rials per dollar.

Many observers see that further depreciation of the rial is inevitable given the nominal and real factors underlying economic fundamentals, the value of the currency and money demand (increased ‘dollarisation’).

For the future stability of the currency, stronger economic fundamentals are necessary. To that end, the government should be focused on expanding production capacity and creating an environment for efficient use of capital. That requires reining in the interest rate cost for borrowing that has been artificially orchestrated to stem the wave of dollarisation, although at the cost of stemming incentives for investment and increasing the cost of borrowing to the government to finance projects for capacity-building.

Exchange rate management should be more transparent, providing for a higher degree of flexibility in line with the underlying fundamentals. This would limit unnecessary interventions by the central bank to arrest the risks of depreciation and artificially increase the interest rate to sustain external stability, although at a cost of compromising the ability of monetary policy to manage domestic priorities and increasing the risk to fiscal sustainability.

Gradually introducing more flexibility in managing the exchange rate by the central bank, in line with the underlying fundamentals, would help to stem depreciation pressures and boost the competitiveness of Iran’s non-energy exports with respect to major trading partners.

For policy implications, priorities should be in place to reach an agreement with the international community to ease sanctions and resume natural inflows of trade and investment to the Iranian economy.

In parallel, both public and private resources should be focused on relaxing binding capacity constraints, capitalising on the country’s oil resources (assuming resumption of oil exports on the international market) towards further diversification of the economy and less dependency on these resources and continued fluctuations in the oil price.

Aligning the real effective exchange rate with the underlying fundamentals will help to boost the competitiveness of non-energy exports. It will also stem inflationary pressures that could prove detrimental to the competitiveness of non-energy exports. Pressing ahead with efforts to diversify the economy and expand capacity will increase the contribution of non-energy growth over time without continued reliance on government spending amid continued tight budgetary resources and fluctuations in oil revenues.

As for the exchange rate system, more transparency in its management, in line with the priorities for the economy, would help to stem speculative attacks. The menu of options could include consideration of a basket peg, based on the shares of trading partners, or a peg to the oil price, assuming the latter continues to have a direct impact on a large share of budgetary revenues and Iranian exports are flowing into the international market without undue constraints.

Regardless of the system, more transparency in the priorities of monetary policy and flexibility to manage the exchange rate in line with fundamentals would foster confidence to stem continued speculative pressures on the rial.

Boosting confidence and focusing policy priorities on improving fundamentals – including by reining in large fiscal deficits and ensuring fiscal sustainability – would result in fewer risks of abrupt sharp discretionary devaluation of the rial in response to long episodes of pronounced over-valuation and foreign exchange shortages. Such episodes – and subsequent overshooting – have proven to be highly disruptive to the country, with lasting adverse social and economic effects.

Figure 1:

Historical values of Iran’s rial since 1990

Figure 2:

Inflation in Iran since 1990