In a nutshell

The Syrian conflict has disrupted the education of millions of children, including the refugees now in Jordan.

The Jordanian government and the international community are working to ensure that all refugee children are enrolled in school and receiving the support they need to succeed, yet there are substantial gaps in enrolment.

Education will have an enormous impact on the wellbeing of refugees, as well as the future development of Syria, should they return, or the state of Jordan, should they remain.

In Syria before the war, enrolment rates of young children were high, with 94-97% of those between the ages of 6 and 11 attending school (League of Arab States and Syrian Arab Republic, 2011). The Syrian conflict has disrupted the education of millions of children, including the refugees now in Jordan.

A large proportion of the refugees are very young, and they face concerning gaps in their enrolment (Krafft et al, 2018). Education will have an enormous impact on their wellbeing, as well as the future development of Syria, should they return, or the state of Jordan, should they remain.

Jordanian government and international community support for Syrian refugees

The Jordanian Ministry of Education and the international donor community have been working to provide Syrian refugees with basic and secondary education in public schools. Basic and secondary schooling using the Jordanian national curriculum are free (Education Sector Working Group, 2015).

There were around 126,000 Syrian children enrolled in formal schools in Jordan in the 2016-2017 academic year and the Jordanian government has hired additional teachers in response to increasing enrolments (Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation, 2017).

Syrians’ education as refugees in Jordan

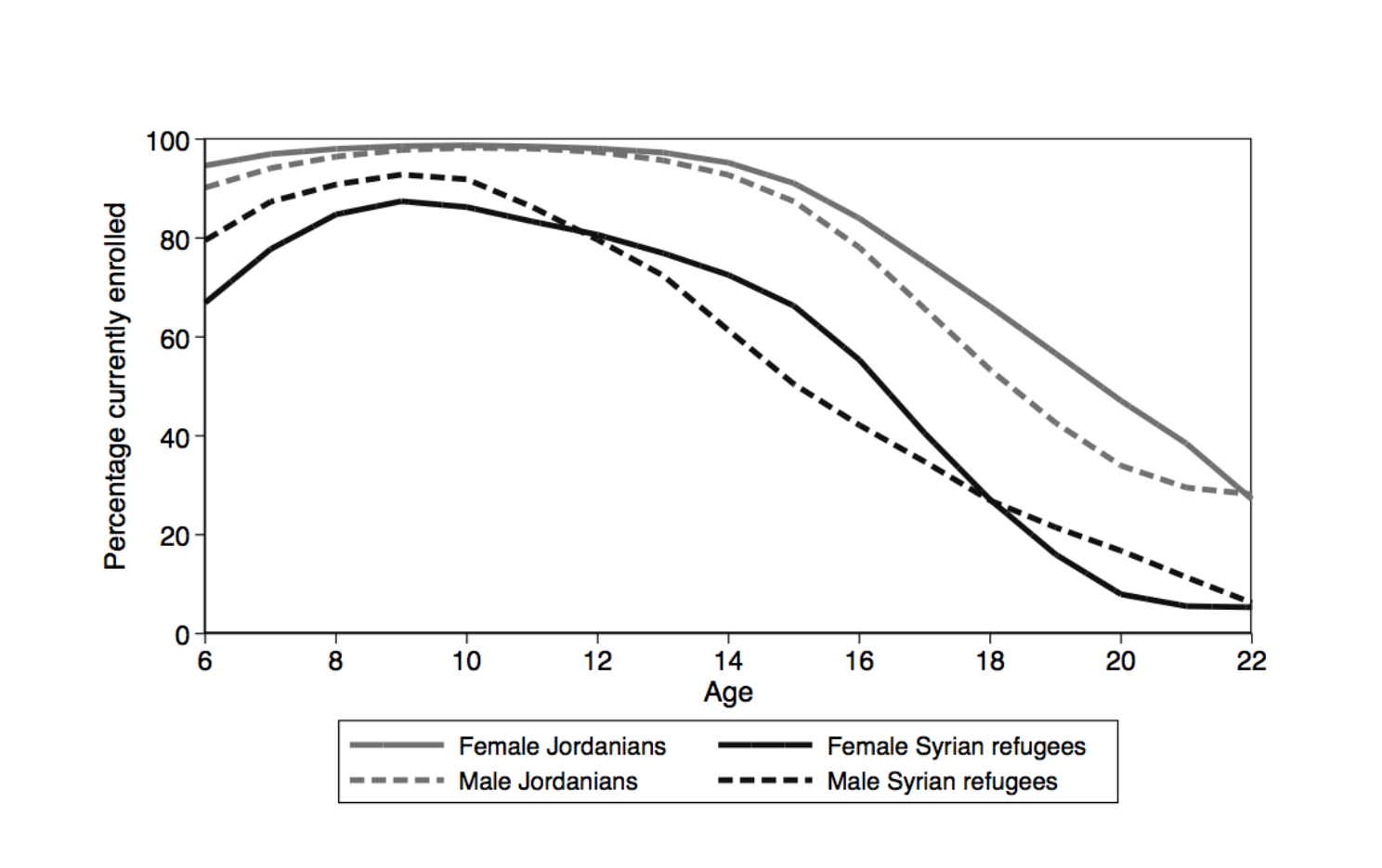

Syrian refugee children who are school-aged are often out of school. In 2016, under 70% of 6-year-old girls and just 80% of 6-year-old boys from Syrian refugee households were currently enrolled in school (see Figure 1). By comparison, enrolment for 6-year-old Jordanians was nearly universal, at around 95%.

Enrolment for Syrian refugees peaked around the ages of 9-10 at about 80-90% of Syrian refugee children and declined for those at older ages. These rates are lower than in Syria in 2009 prior to the conflict (League of Arab States and Syrian Arab Republic, 2011), although the particular group of Syrian refugees now in Jordan are close to what their enrolments were before the conflict.

Enrolment at older ages was less than universal in Syria prior to the conflict but was above 70% up until the age of 14 and around 50% at the ages of 16-17 (League of Arab States and Syrian Arab Republic, 2011). In Jordan, Syrian refugees’ enrolment rates at these ages are much lower than for Jordanians, slightly lower than Syria nationally pre-conflict, and near the pre-conflict enrolment rates of the particular group of Syrian refugees now in Jordan.

Figure 1:

Current enrolment in school (percentage enrolled), by sex and age, Jordanians and Syrian refugees aged 6-22, 2016

Source: Krafft et al, 2018

Syrians primarily left school due to conflict

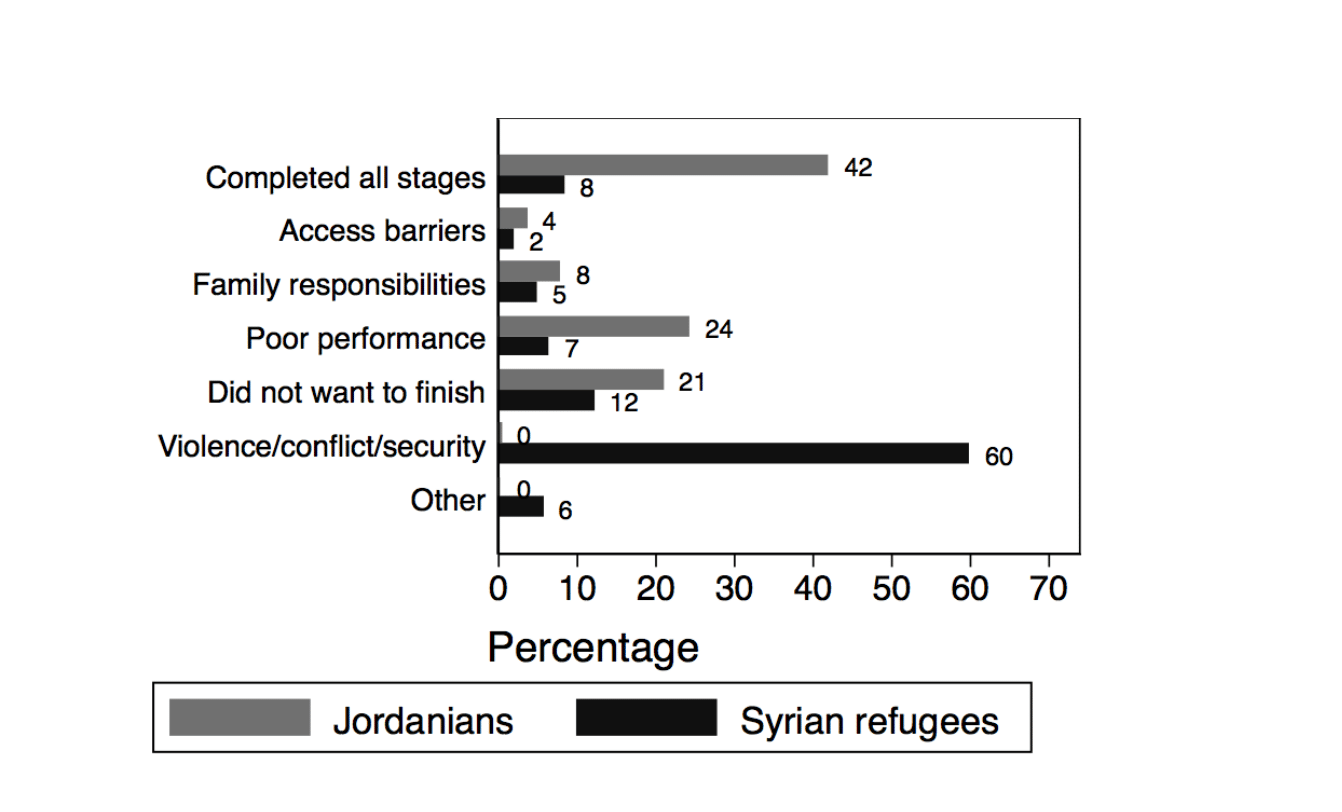

Compared with Jordanians, Syrian refugees report different reasons for not being in school (see Figure 2). Among those not in school who left in 2011 or later, only 8% of Syrian refugees were not in school because they had completed all stages of education compared with 21% of Jordanians. The vast majority of Syrian refugees who left school did so due to violence, conflict or security issues (60%). The next most common reason was that they did not want to finish (12%), potentially due to struggles in school.

Figure 2:

Reason for leaving school (percentage), left school in 2011 or later and out of school in 2016, Jordanians and Syrian refugees, 2016

Source: Krafft et al, 2018

Gaps in literacy for refugees

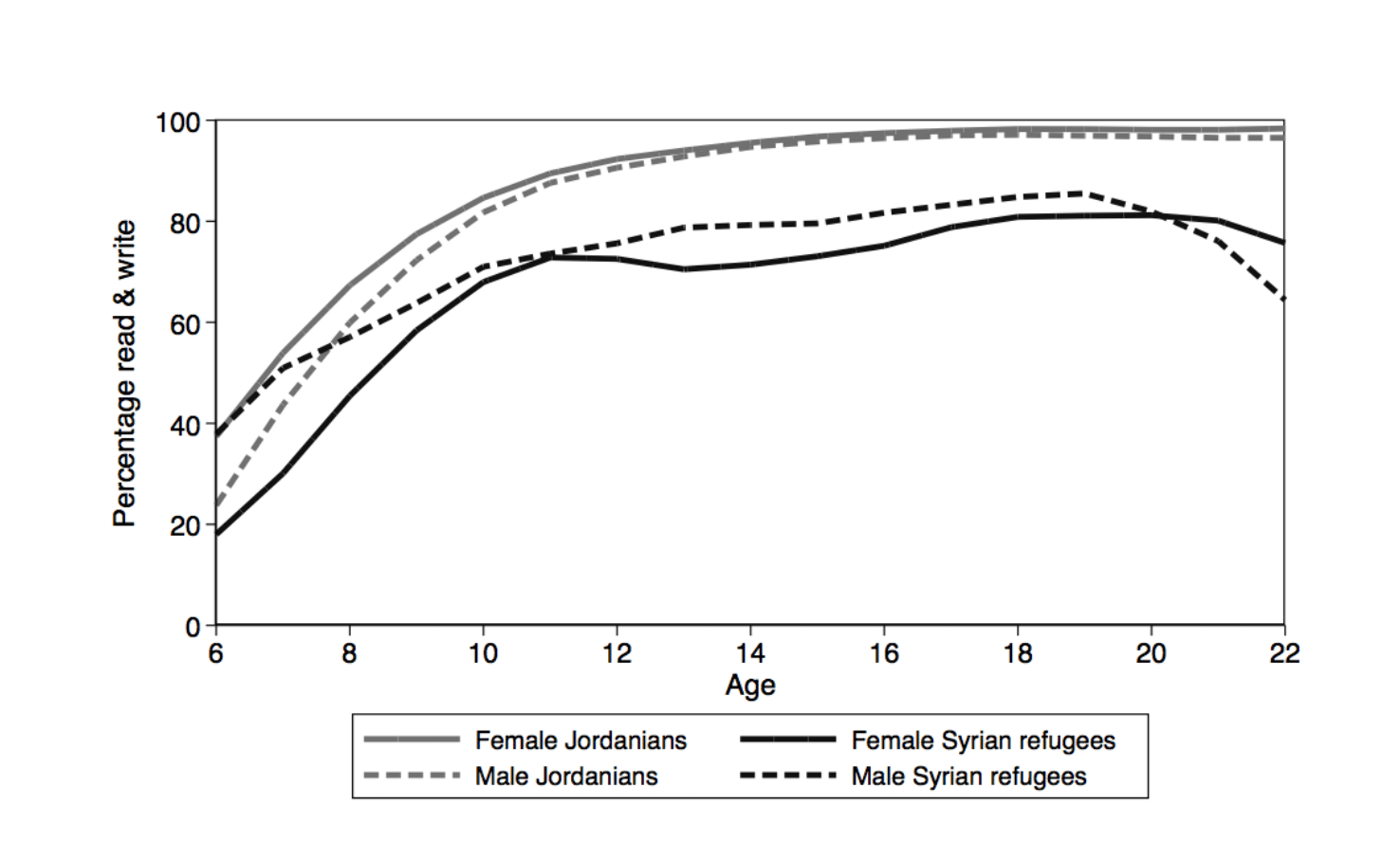

Lower enrolments in school and interrupted schooling mean that Syrian refugees in Jordan often lack basic literacy skills. Figure 3 shows how the ability to read and write varies with age and nationality in Jordan. In part due to lower enrolment in school (see Figure 1), young Syrian girls are at a particular disadvantage in terms of literacy.

While Jordanians universally are literate by their teens, at most 80% of Syrian refugees aged 6-22 can read and write. Interruptions in schooling in Syria as well as gaps in enrolment in Jordan are likely to contribute to illiteracy among Syrian refugees.

Figure 3:

Ability to read and write (percentage), by sex and age, Jordanians and Syrian refugees aged 6-22, 2016

Source: Krafft et al, 2018

Current initiatives and future plans for refugee education

The Jordanian government and the international community are working to ensure that all children are enrolled in school and receiving the support and materials that they need to succeed.

Relatively rapid expansion of school access has occurred in part through adding second shifts to schools to accommodate Syrian refugees. Multiple shift schools may reduce both the quantity and quality of instruction that students receive. The timing of shifts may also be a barrier to attendance (Education Sector Working Group, 2015; Human Rights Watch, 2016).

Historically, Syrian refugees required documentation to register in public schools. Documentation requirements were initially waived for the 2016 school year and the policy was made permanent in 2017 (Al Abed, 2017; Jordan Times, 2016).

This historical policy, combined with a rule that children more than three years older than their grade level cannot enrol, means that many of the out of school children who have been in Jordan (and out of school) for a number of years cannot return to formal schooling.

Non-formal education is struggling to fill the gap for those left out of the formal school system. For children under 12, there are currently catch-up classes, to try to cover multiple years of material and enable them to re-enrol in formal education.

For older children, drop-out programmes may provide them with learning opportunities outside the standard formal curriculum. To date, catch-up classes have helped around 3,000 children and drop-out programmes have helped 5,000 (Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation, 2017). Scaling up these classes to reach more of the nearly one hundred thousand out of school children is a critically important policy priority.

Ensuring the Syrian children who enrol are able to persist and succeed in school is a complex challenge. Struggles in school as well as challenges at home, such as the need to contribute economically, all play a role in drop-outs (Education Sector Working Group, 2015). Increased support for transport and learning materials for financially vulnerable families are important priorities, and identified as such by education stakeholders (Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation, 2017).

Learning supports in and out of schools are also critically important. Makani centres, run by UNICEF, are one example of child-centred education support spaces (UNICEF Jordan, 2017). Makani centres provide academic support for children in school to help them succeed, and basic learning opportunities for children out of school.

Continued support for children who are enrolled in formal schooling and opening up additional educational avenues for children who are currently out of school will be essential to ensuring that the young Syrian refugees in Jordan have the skills to succeed in life. Education is critically important to their ability to contribute to Jordan, should they remain, or rebuild Syria, should they return.

Further reading

Al Abed, Mahmoud (2017) ‘Jordan Allows Syrian Children with No Documents to Join Schools: Officials’, Jordan Times (24 September).

Education Sector Working Group (2015) ‘Access To Education for Syrian Refugee Children and Youth in Jordan Host Communities: Joint Education Needs Assessment Report’, UNICEF.

Human Rights Watch (2016) ‘We’re Afraid for Their Future’: Barriers to Education for Syrian Refugee Children in Jordan’.

Jordan Times (2016) ‘HRW Commends Positive Steps on Education for Syrian Children’ (23 August).

Krafft, Caroline, Maia Sieverding, Colette Salemi and Caitlyn Keo (2018) ‘Syrian Refugees in Jordan: Demographics, Livelihoods, Education, and Health’, ERF Working Paper No. 1184.

League of Arab States and Syrian Arab Republic (2011) ‘The Family Health Survey in the Syrian Arab Republic, 2009 (Arabic)’, Cairo, Egypt.

Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation (2017) ‘Jordan Response Plan for the Syria Crisis: 2018-2020’, Amman, Jordan.

UNICEF Jordan (2017) ‘Education’.