In a nutshell

The roots of the current protests are not merely economic but also political; borne of repeated political failure.

Ignoring citizens’ concerns and embracing the quick and easy path of repression will only further destabilise this country – be it through revolution, radicalisation or the return of dictatorship. This is the main lesson of the Arab Uprisings.

Tunisia’s true friends would be wary of letting such mistakes happen again.

Tunisia is back on a knife edge – here’s why

Pamela Abbott, University of Aberdeen and Andrea Teti, University of Aberdeen

While celebrating the seventh anniversary of the ousting of president Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali, Tunisians have been demonstrating against their government. Thousands have been taking to the streets in Tunis and throughout the country, in some cases leading to arrests and running battles with the police.

The focus of the protests has been the government’s austerity budget, which includes hikes to the prices of basic goods and services. This, the protesters argue, will make life even more difficult for ordinary Tunisians who are already struggling to get by.

It is the latest of numerous demonstrations against the government and its economic policies, which have been increasing since 2015. So what is going on, and where should the country go from here?

Vive la revolution?

Tunisia made international headlines in 2011 when mass demonstrations erupted, inspiring the famous wave of Arab Uprisings that swept through the likes of Libya, Egypt and Syria. Over a quarter of Tunisians participated, backed by the overwhelming majority of the country’s 11m inhabitants.

The protesters were demanding “isqaat an-nizaam”, the downfall of the regime. This didn’t just mean the overthrow of Ben Ali and his cronies, but an end to a system shot through with corruption, leeching wealth from ordinary citizens to the rich, and denying people jobs and a decent life – all under the façade of electoral democracy.

Tunisians’ lived experience has been rather different. By 2014, the Arab Transformations survey showed that the hopes and expectations of the revolution had turned to anger at the failure of successive governments to deliver on promises of economic reform, job creation, and responding to people’s needs.After the revolution, moves towards truly free elections gave Tunisians some hope that they would enjoy real democracy; that politicians would finally hear and heed their needs. Indeed, international commentators and academics have hailed the country as the lone bright spot in a region beset with civil wars, counterrevolutions and open conflict.

Indeed, according to our ArabTransformations survey from that year, Tunisians did not see their country as a democracy: few saw it as outright dictatorship (14%), but fewer still (11.5%) saw it as fully democratic. If it were fully democratic, went the prevailing view, it would heed the will of the people.

In our book published this month, we trace how three years after the revolution, people still saw lack of employment and corruption as the major problems facing their country. They had little trust in government, political leaders, religious leaders, civil society, or even fellow citizens.

They thought that their own and the country’s economic situation had deteriorated since 2010; they were fearful of terrorism and worried about security. Half the population were worried about their employment, and 60% of young people were worried about job opportunities. Where Ben Ali’s removal had been greeted with euphoria, now there was mounting disillusion and despair.

From despair to …

Disillusion has since kept building, according to the 2016 Arab Barometer. Successive governments have either been unwilling or unable to fulfil their citizens’ demands for economic and political inclusion.

Economic “liberalisation” before the revolution brought praise from the IMF. But measures including privatisation, public spending cuts and trade liberalisation increased unemployment, with most people seeing no benefit from economic growth. Ben Ali held on to power and corruption and crony capitalism got worse.

Since the revolution, Tunisia has continued to implement these failed policies – at the behest of the international financial institutions and Western governments. The IMF postponed part of Tunisia’s most recent $2.8 billion (£2 billion) loan last year, only reinstating it after the government agreed to accelerate cuts to public spending.

These policies have continued to produce economic stagnation, increased government debt and reliance on development assistance and soft loans. Corruption remains a problem and the unemployment rate is still in double figures, especially among university graduates. Tourism continues to struggle after the terrorism of 2015, even though it has been improving.

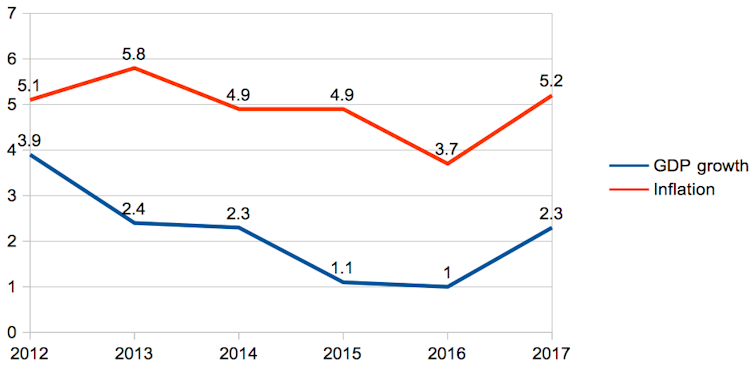

Growth and inflation

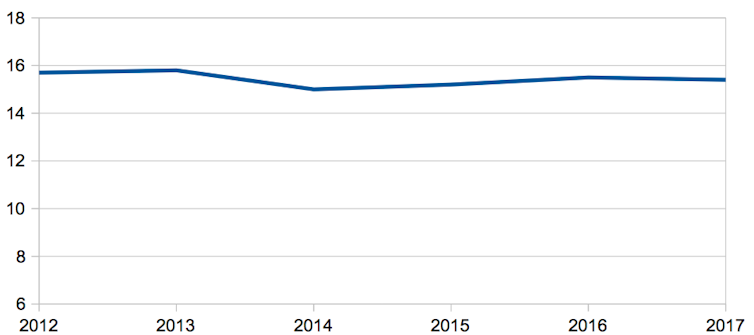

Unemployment

This is the environment into which the government is pitching its new Finance Act. It includes a one-point rise to VAT for many products, higher taxes on bank profits and a new 1% social security tax on employees and companies.

Prime minister Youssef Chahed has said the austerity measures will mean only one more difficult year for Tunisians, though experts are divided about whether they will work. Other measures include selling off government stakes in Tunisian banks and hacking back the number of public sector employees.

In our view, Tunisia’s austerity has been counterproductive and will continue to be. The government should instead structurally reform the tax system to make it more redistributive; while fighting the major problems of tax evasion, corruption, smuggling and parallel trading – where products are imported without the permission of the manufacturer.

Whether the government has the will or authority to pursue such solutions remains to be seen. It doesn’t help that it is weak and riddled with in-fighting between coalition partners.

Tunisia’s international partners meanwhile need to recognise that it’s not enough to just improve the country’s voting system. Guaranteeing social and economic rights – creating decent jobs, tackling corruption – are the democratic substance without which elections remain empty promises.

Tunisia, like the other countries in the region, is unstable because it has failed to address the very issues that fuelled the revolution of 2011. People want more than formal political freedom and freely elected governments; they want leaders who deliver on the substance that goes with the promise of democracy – not just ballot boxes but tangible fairness.

![]() In short, the roots of the current protests are not merely economic but also political; borne of repeated political failure. Ignoring citizens’ concerns and embracing the quick and easy path of repression will only further destabilise this country – be it through revolution, radicalisation or the return of dictatorship. This is the main lesson of the Arab Uprisings. Tunisia’s true friends would be wary of letting such mistakes happen again.

In short, the roots of the current protests are not merely economic but also political; borne of repeated political failure. Ignoring citizens’ concerns and embracing the quick and easy path of repression will only further destabilise this country – be it through revolution, radicalisation or the return of dictatorship. This is the main lesson of the Arab Uprisings. Tunisia’s true friends would be wary of letting such mistakes happen again.

Pamela Abbott, Director of the Centre for Global Development and Professor in the School of Education, University of Aberdeen and Andrea Teti, Senior Lecturer in International Relations, University of Aberdeen

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.